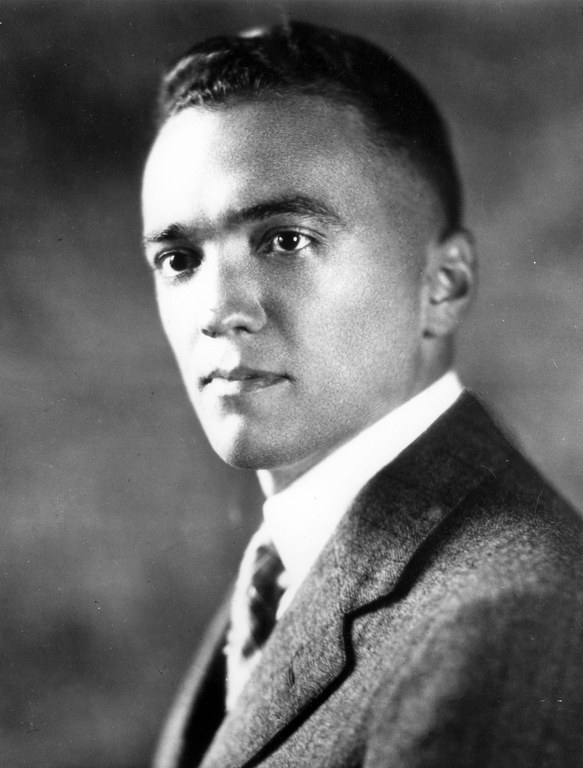

J. Edgar Hoover, director of the Bureau of Investigation, 1924. Photo credit: Federal Bureau of Investigation.

The Bureau of Investigation has long labored on under a plethora of misconceptions from all sides through the years. Even friends get shot in the crossfire. Its record during the Coolidge administration often gets blurred with the tone and conduct of other administrations, before and after, and presents a confused picture blending time, space, and personalities together until few honestly know fact from fiction.

A favorite whipping post is the long-time director of the Bureau, J. Edgar Hoover, who usually receives the vitriol of his critics as the last and final word on all we need to know about the man and his legacy. But, what if there was more to the story?

The Bureau is part of the Department of Justice, and always has been. It was not entrusted under the law with Prohibition enforcement (which belonged to the Department of Treasury) nor was/is it tasked with protective services as if it were an extension of the White House Detail of the Secret Service. Local jurisdictions remained protected by local police departments not Bureau agents. The 20s and early 30s are incorrectly labeled as the “lawless years,” as if the burden of Prohibition enforcement fell solely on the Bureau’s shoulders. It simply did not. Though “federal” would not officially be part of its name until 1935, there was no blurring of its responsibilities. It was, just as its name suggests, entrusted with investigating federal crimes after the suspected acts are done.

J. Edgar Hoover began with the Department in the Wilson administration. When Coolidge came aboard, and soon thereafter his new Attorney General, Harlan Fiske Stone, a genuinely different direction swept across the Bureau. It is known as the “great purge,” a sweep of personnel so expansive that it earns the name even now. It is typical that the old system of appointing political hacks and repaying long-time debts to friends had prevailed over the Department as a whole, and the Bureau in particular. Summoned to the office of Attorney General Stone, it appeared likely that J. Edgar would swiftly join his boss, William Burns, whose walking papers had been issued days before. A higher standard was expected of the Bureau than had guided in the past.

The “dollar-a-year” men had to go, the political appointees crowding the roster. Hoover had to be the one to wield the ax. J. Edgar immediately began clearing out hundreds of operatives positioned by campaign pledges among the Bureau’s 650 employees. This was no game of musical chairs either. Once dismissed, they were to remain out. By 1928, he had initiated a course of professional standards for every new agent entering the Bureau. That was not all, the entire mission of the Bureau was required to change. Stone, outlining it all in 1924, explained the Bureau’s new purpose. As Stone put it,

There is always the possibility that secret police may become a menace to free governments and free institutions because it carries with it the possibility of abuses of power that are not always quickly apprehended or understood…[The Bureau of Investigation is] a necessary instrument of law enforcement. But it is important that its activities be strictly limited to the performance of those functions for which it was created and that its agents themselves be not above the law or beyond its reach.

The Bureau would professionalize or be shut down. No more would political favors determine its personnel. It had to operate on the basis of competent knowledge of the law and “proven ability” to earn promotion. Hoover’s rapid response demonstrated that the young J. Edgar understood the Attorney General completely. Hoover also had unimpeachable recommendations, including that of the unquestionably honest Commerce Secretary, Herbert Hoover. That alone would not have spared him but as a result of his decisive actions, J. Edgar would be allowed to keep at it. But, lest we think this was some cunning attempt on the young director’s part to survive, he remained at it long after Stone had moved to the Supreme Court. Hoover was simply not the insidious monster he is made out to be by his partisan critics, the very voices who cemented the narrative of FBI history as a scapegoat for xenophobia and hysteria for decades. In truth, it is the critics who have relished when facts are confused and individual responsibility is kept at its murkiest. These critics revel in the darkness.

Stone would continue to outline what the Bureau was, now with Coolidge in charge. The Bureau was not in the game of entrapment or political witch hunts. It had a solemn obligation under the law to remain an impartial investigator of facts not hearsay, or mere opinion:

[The] Bureau of Investigation is not concerned with political or other opinions of individuals. It is concerned only with their conduct and then only with such conduct as is forbidden by the laws of the United States. When a police system passes beyond these limits, it is dangerous to the proper administration of justice and to human liberty, which it should be our first concern to cherish.

As one of those best positioned to know truth from fiction, Hoover’s long-time lieutenant, “Deke” DeLoach wrote: “Hoover’s quick action convinced Stone that Hoover was serious about reforming the bureau, and he kept him on the job. Hoover stuck to Stone’s principles throughout his career, and in many ways the bureau that Hoover remade was a product of Stone.”

Predictably, Stone also gets stonewalled as far as his legacy is concerned. Yet, the same Stone who was not only Coolidge’s appointment for Attorney General also became Coolidge’s lone appointment to the Supreme Court while remaining the solid friend of Cal’s successor Herbert Hoover. The same Stone would become Frankllin D. Roosevelt’s appointment to Chief Justice in 1941 and sharply criticize not only the New Deal but also his old friend’s response to it, that of former President Herbert Hoover:

I think even more could be said about present tendencies to depart from traditional forms of democratic government under the Constitution. The steady absorption of power by the President, the failure of Congress to perform its legislative duties, the absence of debate in Congress, and of open public discussion of the public’s problems, the creation of drastic administrative procedures, without legislative definition and without provision for their review by courts, are, I believe, an even greater menace than the programs for whose advancement these sacrifices have been made.

Herbert Hoover would reap decisive repudiation for his line of attack, published as a book entitled The Challenge to Liberty in 1943. Stone, trying to spare him, had warned that the people were not in a place ready to receive such abstract sermonizing. The people would always get what they tolerated…and, as Coolidge put it, deserved.

The problem, as it always turns, relies on the quality of leadership. By that time, the people were prepared to accept the abuses done to traditional limits if it might yield a way out of the mess, a path freed of the current storm, be it Depression or World War. President Roosevelt’s leadership had set a tone and no court or law enforcement body could operate in defiance of the popular will, the people’s willingness to go where things had not before gone. It was not the Court’s place to lead the people by the nose any more than it was the Bureau’s job to prosecute individuals in search of a crime. Yet, they all had to operate beside or, in the Bureau’s case, constantly beneath, the direction set by the President. Yet, the Director had taken an official oath as well and only he would answer for his own violation of it. J. Edgar remained vigilant to his oath and obligation, keeping the ember alive started by Coolidge’s Attorney General Stone in 1924. Yet, J. Edgar Hoover knew (a fact former President Hoover was much less adept to grasp) that without a White House or popular sentiment solidly behind him, his would be a voice in the wilderness, and often a voice they would seek to silence, mischaracterize, and blame for the dereliction of others. Our impression of the man is still too often colored by the success with which they have tainted him and Coolidge’s housecleaning of the Justice Department.

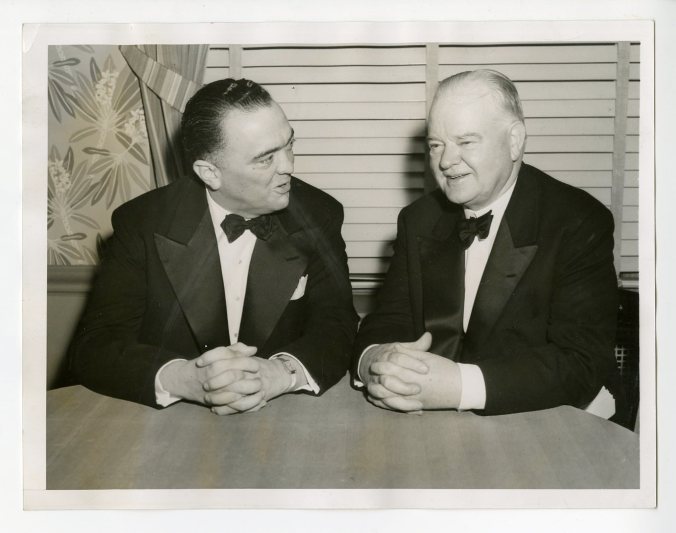

Director J. Edgar Hoover (left) and former President Herbert Hoover (right), 1944. No relation by blood, they only happened to share the limelight for four decades. Photo credit: National Archives.