It has been with great interest that we have watched the revitalized consideration of Gilded Age Presidents over the last number of years. As is frequently the case in the Presidential ratings game, however, the methodologies and results reveal as much, if not more, about the persons presenting a new study or set of conclusions. While some findings stubbornly persist despite compelling refutations to the contrary, we find that the debate is never completely settled and for that we are thankful. There will always be something new to bring to the conversation. The quest will bring us back to leaders undeservedly shoved in the closet of presidential failure, infamy, and seclusion.

President Ulysses S. Grant (1869-1877)

It appears with the growing return of Grant to higher regard and the reassessment of Arthur, we also begin to see a boost for Hayes. His Presidential Center up in quiet Fremont, Ohio, and its website have certainly come a long way in the last decade. The findings of associate professor Mark Zachary Taylor (who could not be a Presidential history enthusiast with a name like that?!) of the Georgia Institute of Technology have come to the forefront after his initial presentation eight years ago for ranking Presidents along eight factors of economic impact. Among his latest papers have been one on Hayes and another on Arthur. He recently spoke at the Hayes Presidential Center and argues that Hayes ranks among the top tier with FDR, Harding, and McKinley. Reported in Fremont’s News Messenger, Professor Taylor’s case is not quite presented as clearly as we would hope. The Messenger seems to be confused by when the Gilded Age (essentially 1870-1900) actually took place and so blends together FDR among the other Presidents of those earlier years. This is certainly not the professor’s fault but it hardly helps lift the opacity over his claims. The correspondent launches us into the Gilded Age but seems to forget that we must leave the Era to venture into a broader discussion of all the Presidents, including that perpetual winner of every category: FDR. One almost laughs to wonder what category FDR would not come first in as far as academic estimation is concerned. As we all know with any survey or questionnaire, it is often the questions one asks that narrows the range of acceptable answers. One of the perks, I suppose, of having almost four complete terms across a time period that defines a great deal of what America has become is that it becomes a chore not to have broken historical records just about everywhere. Like a quarterback who went on to surpass the statistics of his predecessors, FDR cannot but stand large and dominating on the popular perceptions of the office and what we expect of those who have followed him. About the only category we can immediately think of is Founding Father Presidents…but then, it depends on how one defines founding father. Under the right conditions, FDR could win that one too.

We all have our biases and Professor Taylor has every right to keep his no less than the rest of us. Just like us, though, he would do well to remember that what is objective and non-partisan to him (his eight economic parameters) is not always objectively so. He admits no system is perfect but there remain very subjective criteria left in his ratings framework. His factor of “vision” is one such example. Who defines vision but the subject? His arguments make for some curious contradictions. I think it is all well-meaning, a product of so many assumptions that have gained unquestioned validity in academia and Professor Taylor has accepted enough of them without challenge.

President Rutherford B. Hayes (1877-1881)

It is very interesting that he rushes past Grant’s achievements (including the reorganization of the Treasury and budgeting systems and more determined stand than Hayes on civil rights in the South) to zero in on the scandals of the Grant tenure while according a much more sympathetic appraisal of Harding, whose administration is often compared to Grant’s. He lauds Hayes for facilitating economic recovery but excoriates Arthur for supposedly doing nothing to mitigate the contained recession of 1884, a much less severe concern than Taylor perceives it to be. All the while, if the 1884 recession was as devastating as Taylor seems to think it was, Hayes receives none of the blame for so short-lived a recovery (beginning 1878) despite the alleged bottom falling out of the boom market just as Garfield entered office in 1881. Somehow Hayes then keeps much of the credit for recovery that returns in 1886, five solid years after Hayes’ departure, all the way into Cleveland’s first term. It seems rather odd if not suspect to surgically award this to Hayes while robbing it of Arthur and Cleveland.

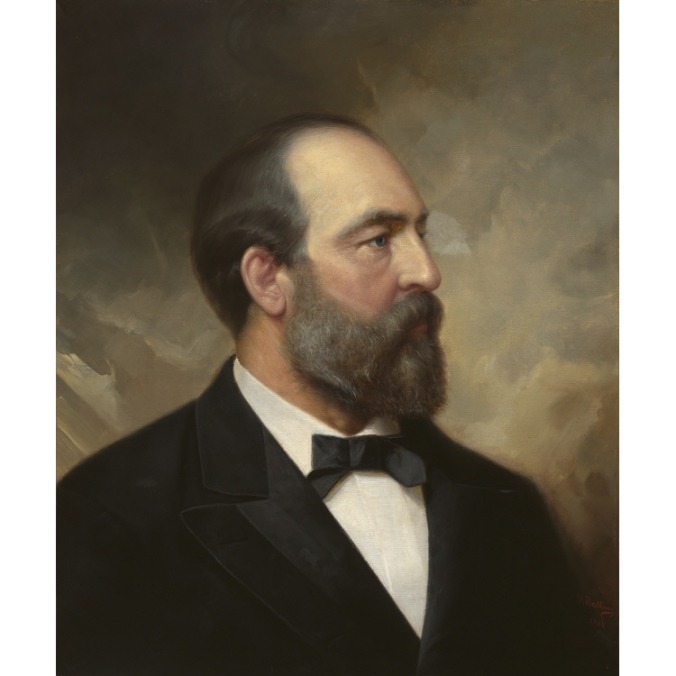

President James A. Garfield (1881)

There is no question that up to 1877, America had never experienced so general and disturbing a disruption between labor and capital. Hayes’ deferential use of federal authority certainly informed later crises but Cleveland would take a much stronger, even unilateral involvement, than Hayes ever did. Yet, Cleveland, who vanquished the Tenure of Office Act, demonstrated a decisive vision on the gold issue and faced the still greater 1893 Panic and Depression receives far lower marks from Taylor. By elevating Cleveland’s second administration (1893-1897) — clearly more difficult than the economically prosperous first term (1885-1889) — Taylor, curiously, does not consider economic prosperity to consistently apply in his own rankings. It seems then economic impact is meant to encompass only selective instances of improvement or expansion. If impact means dramatic upheaval of the economy, indifferent to its growth or health, then we can begin to see why FDR ranks first and LBJ’s 60s stand higher in Taylor’s apparatus than Calvin Coolidge’s 20s.

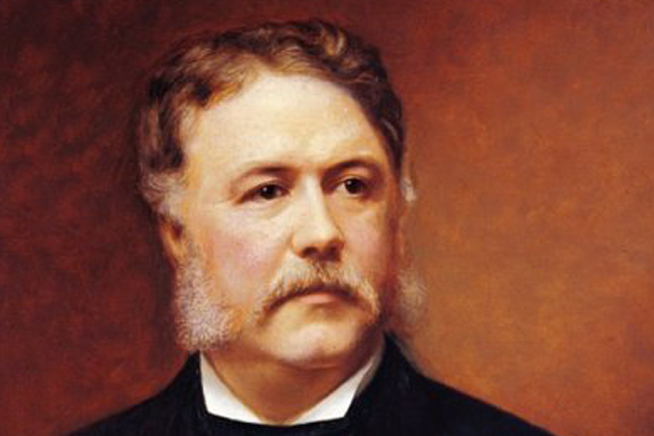

President Chester A. Arthur (1881-1885)

How impactful a President is remains heavily tipped in the balances toward one who intervenes rather than presides. Professor Taylor conceals little of his contempt for the latter in his damning treatment of Arthur. Arthur’s effective use of the veto (on the very same conflict over Chinese immigration for which Hayes is praised) and his principled backing of a definitive direction for civil service reform (the Pendleton Act), whatever one thinks of his pre-Presidential past, is remarkable and deserves our respect not so jaundiced a view as Taylor’s. Even Arthur’s critics at the time had more charity for “Chet” than the good professor allows. It seems Hayes’ character in office fostered trust but Arthur’s integrity, in contradiction to his life before office, means nothing to Professor Taylor.

President Grover Cleveland (1885-1889 and 1893-1897)

But, as usual, he doesn’t stop there. No one then or acquainted with Cleveland’s independent-minded vision of his office and his agenda (he made the gold standard – and the defeat of bi-metalism – a central plank of his tenure) can say he lacked a clear idea of what he wanted to accomplish on economics…or anything else, for that matter. Both terms considered, Cleveland should stand tall within Taylor’s criteria yet he does not. The man who is arguably the most actively Jacksonian President of the Gilded Age hardly earns so low a ranking in the good professor’s supposedly data-driven economic impact scale. Benjamin Harrison seems to fit his failing GPA (in Taylor’s rankings) due to his complicity in the first billion-dollar Congress but national debt reduction, spending and tax cuts, budget surpluses, not to mention economic expansion the likes of which we have rarely known as a country seem to count for Harding but not for Coolidge, who stands at the peculiar #14 (as President) and #25 (as an Administration), directly behind Taylor’s namesake, President Zachary Taylor. Apparently 1849-50 rivals the Roaring Twenties in economic impact.

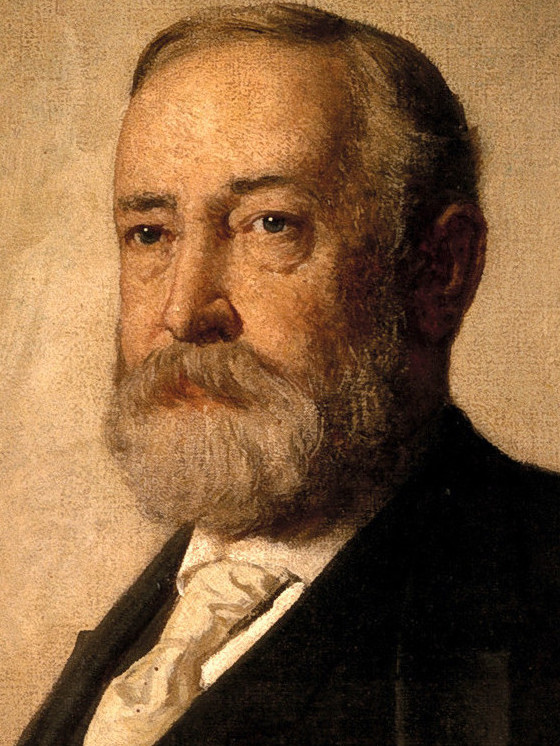

President Benjamin Harrison (between the Cleveland presidencies, 1889-1893)

All of Professor Taylor’s measurements (increase of national wealth, unemployment reduction, inflation minimization, reduction in the balance of payments burden, currency strength, interest rate changes, stock market performances, and even that catch-all, “reduction in economic inequality”) should find abundant reason to commend the Twenties — Harding and Coolidge both — yet, again, he neatly splits the baby: excising the singularity of their vision and the power of the results they wrought. It was not Hayes’ passive facilitation but an active and unrelenting effort on the part of Harding to begin and Coolidge to continue the implementation of the Budget and Accounting system along with:

- Ten consecutive budget surpluses (which neared and even surpassed on one occasion the $1 billion mark annually under Coolidge)

- An economy that grew 42% between 1921-1929, saw new construction nearly double in less than a decade, witnessed the growth of real GNP by 4.2% annually

- Unemployment down to an average 3.7%, seeing inflation evaporate to an average 1.56% during Coolidge tenure while wages rose for multiple sectors of the economy and the Dow Jones blossom to an average of 313.54 in 1929, more than triple its average closing price (90.01) in 1920. The Stock Market, investment in which proliferated widely among earners across income brackets, experienced an average growth of 20% a year.

- The national debt (principal and interest combined) shrank by a whopping one-third of its total size

- Foreign trade climbed a billion dollars annually every year after 1922 (keeping America a creditor nation)

- Harding-Coolidge had their economic dislocations too and successfully weathered a depression (1921), and two recessions (1924 and 1927)

- They shifted the burden of income taxation (indisputably a vital factor in any consideration of economic impact) from the lowest earners (where it had been) to the highest incomes (those earning $150,000 and above carrying 55.26% of the total tax liability by 1929). That same year, 1929, the bottom 80% of income earners paid 35% of individual income taxes while the top 20% paid the remaining 65% of the total tax burden. A mere 4 million filed individual returns by 1930 in a population of 123 million.

If nothing else, this little table from Warren Devine’s research, cited by Professor Gene Smiley on Average Annual Rates of Labor and Capital Productivity Growth illustrates well the unprecedented nature of growth during the Twenties:

Labor Productivity Capital Productivity

1899-1909 1.30% -1.62%

1909-1919 1.14% -1.95%

1919-1929 5.44% 4.21%

1929-1937 1.95% 2.38%

This was no case of the wealthiest 5% making all the money while everyone else limped along. The economy of the 20s was creating entirely new sectors, reaching into previously unexplored directions and was anything but a few CEOs and white collar executives monopolizing the flow of capital. Citing the top 5% statistic as an index measure, as if that percentile remained static — containing the same individuals year after year after year, a situation that clearly did not exist — Taylor skips a consideration of wages, national debt payments and other vital factors that should weigh into a full reckoning of economic impact. That he does not do so for the Coolidge 20s indicates a departure from the non-partisan analytics he sets out to apply. He is too quick to lift Hayes and too slow to provide the same standard to others. An exception to this haste may be his high rating of Millard Fillmore, whose time undeservedly relegated to the shadows might be seeing a little more light than he has been accorded these 170 years. To gain more perspective than Taylor gives us, however, I suggest Chris DeRose’s The Presidents’ War and Robert Rayback’s Millard Fillmore. Back to the point, people rose and fell across the brackets in Coolidge’s 20s just like they do today. An increasingly affluent middle class continued to rise that encompassed thriving African-American and naturalized immigrant communities and unfolded to an extent unseen before these years. No, everyone did not rise at the same rate, just as it was not realistic to expect so. This does not refute the fact that improvements across a broadening cross-section of the population were actually felt or underway in places they had never before appeared. Rates of rise or fall ultimately rest with each of us not in the hands of any President or government figure, whoever is in office. We are hardly qualified to blame Harding-Coolidge for not moving faster in eight years than it is taking us, a century later, to arrive at economic perfection ourselves. When we have done so, then we might have occasion to criticize them.

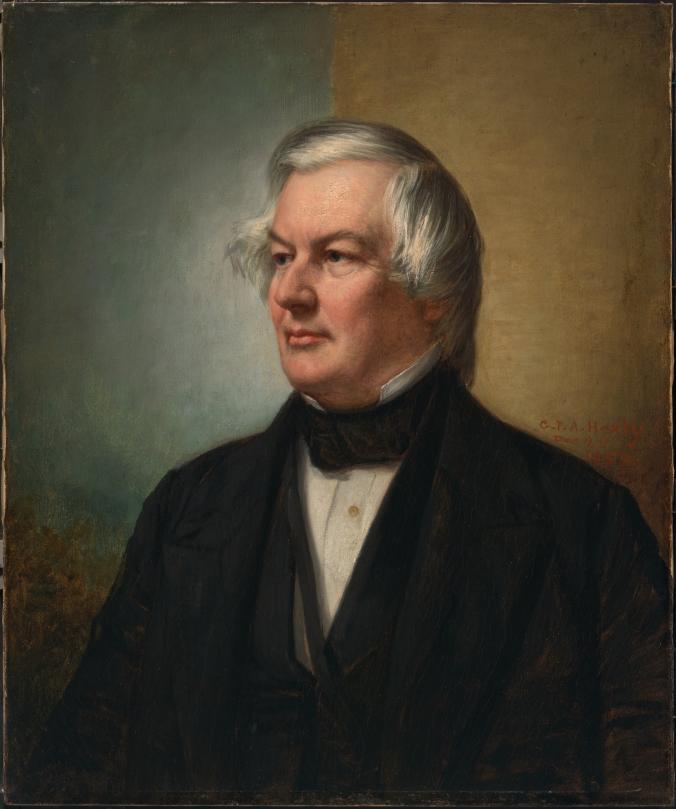

President Millard Fillmore (1850-1853, not one of the Gilded Age Presidents but his time of reappraisal may be coming)

The Harding-Coolidge Normalcy Agenda didn’t stop there either. Harding-Coolidge formally ended hostilities with the Central Powers, settled war debts for dozens of nations including a renegotiation of the German debts in the Dawes Plan, ratified the Kellogg-Briand treaty, arbitrated disputes in Mexico, Nicaragua, Peru & Chile as well as across Latin America while passing measures to reform the judicial system, inaugurate prison reform, reconstitute the diplomatic service, attempt Prohibition enforcement, unveil overhauls of air commerce, and radio technology law, not to mention disarmament initiatives and take on adequate naval construction plans while keeping the peace for more than a decade. Obviously, then, nothing of any consequence (economic or otherwise) happened in Coolidge’s time…?!

But then, when the primary basis for understanding “Silent Cal” comes from the equivalent of the Reader’s Digest Condensed Series for Presidential biographies (The American Presidents Series edited by Arthur Schlesinger, Jr.), it is not surprising that Professor Taylor echoes the image of Coolidge he has received from David Greenberg. He seems oblivious to Robert Sobel’s work or that of Paul Johnson in Modern Times. It is understandable, given the year was 2012, that Professor Taylor would not incorporate Professor Michael J. Gerhardt’s findings in The Forgotten Presidents, published in 2013 nor Amity Shlaes’ biography Coolidge, also out that same year. Yet, he seems to ignore Steven G. Calabresi and Christopher S. Yoo’s work, The Unitary Executive and only lists Professor Alvin S. Felzenberg’s The Leaders We Deserved (and a Few We Didn’t) without countenancing any of his cogent observations about Coolidge. We find Taylor’s blanket dismissal of Cal here:

As vice president, Coolidge had been allowed to join Harding’s cabinet meetings, but he did not participate. He was not deeply involved in any Harding agenda items. Instead he was given speeches to make, but otherwise his biographer reports that ‘Coolidge wasn’t much of a force in politics, the capital or the nation.’ After his succession to the presidency, Coolidge retained Harding’s cabinet and policy agenda at first. He asserted his own stamp on it only in 1924.

It is not quite accurate to interpret Cal’s five and a half years as President (1923-1929) through the lens of the preceding two and half as Vice President (1921-1923). Even as V. P., Coolidge certainly did participate in Cabinet meetings and other aspects of Harding’s agenda. He presided over Budget Bureau meetings in the President’s absence and attended them all anyway. Cal says his involvement in the Cabinet meetings helped prepare him immensely when the Presidency suddenly came to him. As far as what Professor Taylor means by retaining Harding’s policy agenda “at first,” we leave it to him to explain. Coolidge obviously replaced personnel over time but it is unclear how he struck off on his own agenda and why that somehow severs a closer continuity with Harding’s high ranking in Taylor’s measurement. That apparently is all there is to say about the otherwise “do-nothing” Coolidge.

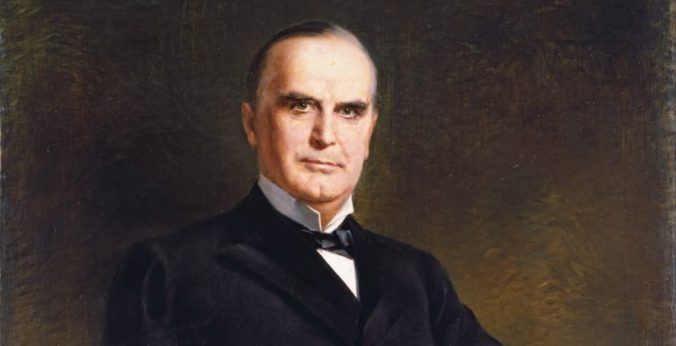

President William McKinley (1897-1901, the last of the Gilded Age Presidents)

It seems, ultimately, that economic impact remains a very fluid, ethereal concept, no less subjective than so many methodologies that attempt to improve the tools for measuring Presidential success. At times, in his haste to eschew Arthur and ignore Cleveland in order to raise Hayes, or promote Harding but dismiss Coolidge, Taylor seems to miss where that forest could have gone if only these trees would get out of the way. He overlooks the more substantial Presidential independence demonstrated by Arthur (for breaking decisively with his past) and Cleveland (who had always exercised his own counsel whatever office he held). Taylor also sidelines the importance of much bigger and far more powerful economic booms like the Roaring Twenties after Harding, downplaying Coolidge’s not unsubstantial role in that event, historic by any measure, for any century. He leaves off the rise of wages across industries to focus merely on the change in the share of aggregate income received by the wealthiest 5%. He selectively visits low unemployment and budget surpluses in Hayes’ time but leaps right over the still larger series of continuous budget surpluses in the Coolidge years, combined at the same time with deflationary prices, shrinking unemployment, thriving GNP and GDP, reliably amassing foreign trade and investment, a reasonably steady pound to dollar value, and an average income per person double in 1929 what it was at the beginning of the decade. This all remains unparalleled even now as the last time America saw steady spending reductions alongside budget surpluses (for more than ten straight years), tax curtailment alongside growing revenues, and all the while taking place with an economy expanding on historic levels in scope, value, and productivity. It was real and if we would somehow penalize Coolidge in presidential rankings for the recession and collapse of the 30s, we should do the same for Hayes in the 1880s. Some gladly do both already but it cannot be done consistently using Professor Taylor’s approach.

President Calvin Coolidge (1923-1929). Sketch by Ercole Cartotto.

The professor certainly offers many helpful insights on how we gauge these leaders, including the point that “greatness” rarely plays any factor in economic impact. The smartest of the smart do not always do well. Brains and prior economic education are inconsequential to the final results, the factors and causes for which rest beyond academic preferences or academic training. For that, if nothing else, Professor Taylor is on to something. Maybe we would do better listening less to the academic status quo.