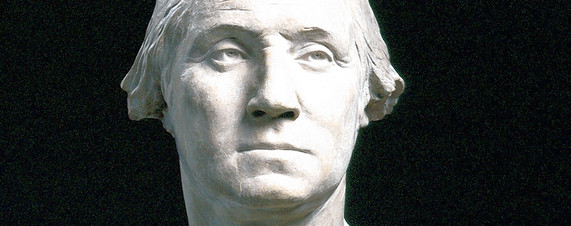

The Houdon bust of George Washington, based on precise measurements from life, recognized at the time as the best rendering of him as he was. The finished statue would be lauded by Washington’s close friend, Lafayette, with the words, “This is the man himself.”

The bicentennial of George Washington’s birth was long anticipated through the 1920s, as 1932 neared. President Coolidge had given acclaimed expression to the significance of the date as it approached, speaking before joint session of Congress on February 22, 1927. But the President, by that time in retirement, took occasion on the bicentennial itself to offer his reflections on the man who really was, as Coolidge put it, the first American. We must ask, what of anything resembling America’s best qualities would there be today without George Washington? There would have been no practical application of any of those ideals.

Published originally by newspapers of national circulation on February 21, Representative Bertrand Snell read Coolidge’s thoughts into the Congressional Record, where it can still be accessed today. What Coolidge wrote eighty-eight years ago speaks with timely clarity:

The careful study of the life of George Washington has an intensely practical purpose. We want to know what he thought and what he did in order that we may be the better able to determine what we ought to think and do now at this difficult time. We shall find it providential that the course of our Nation was largely directed in our formative period by a man who was so human, so devoted in establishing a government of the people, and so experienced in private business that he was able to apply sound business sense to the promotion of the public welfare.

The celebration of the bicentennial of the birth of the first America which occurs on the 22nd of February of the present year, should, of course, include a proper estimate of him as a great statesman and a great soldier. It is in that character that we have come to think of him. He was both, and as such is entitled to all the praise that can be lavished upon him by the most eloquent. But that is not enough. It does not tell us of the real man nor give us any insight into how he became great. We shall fail in the most desirable comprehension of him unless we turn to the more practical examination of his growth and development and try to learn how to do things by finding out how he did them.

There are two kinds of biography which fall short of giving their readers the help which should be secured from an acquaintance with great men. Some of them endow their subjects with all virtue and all wisdom. Such characters appear removed from the reach of common people. They may admire and worship, but they do not feel any kinship. They gain only the impression of a superior being dwelling apart from his fellow men. It would seem almost sacrilege to attempt to imitate him or hope to be like him. Others, proceeding in an opposite direction, represent great men as devoid of most good qualities who have reached the positions they hold by being crafty and successful imposters. They are made to appear unworthy of credit or admiration and left to the inference that all greatness is a sham and a pretense. The logical conclusion is meant to be that there are no heroes and nothing is holy. Neither one of such portrayals is in accord with human nature or the truth.

Call of the Sea, 1747, Jean Ferris’ 1920 rendering of fourteen or fifteen year old George Washington feeling the tug of a career on the ocean. His mother persuades him to stay. Photo credit: Vermont Historical Society.

George Washington was well born. His father was a mature man nearing the forties and his mother was a young woman in the twenties. Neither of his parents had any place by reason of artificial rank or title, but they belonged to that great and strong aristocracy which ennobles itself by the power of its own achievements. They were both people of the world. Tradition has it that they first met in London, where the father was accustomed to go on his business as a successful Virginia planter.

It was a serious household into which this boy came. The young mother read the Bible and Matthew Hale’s Contemplations and Meditations. At a very early age her son appears to have been provided with a book of sermons. Of course, membership in the church and regular religious worship were the practice of the family. Faith was a reality in the Washington home. The Bible, the church, the sermons of pious men were all a source of inspiration for the practical affairs of everyday life.

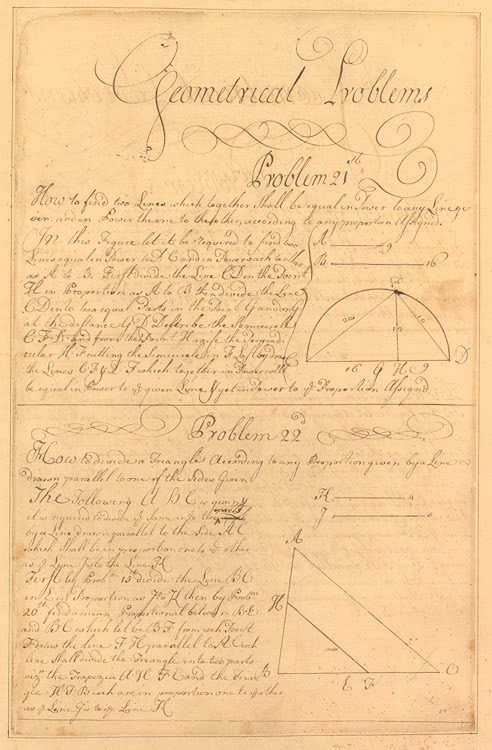

While we do not know much of the details of the early education of Washington, we know enough to inform us on the development of his mind and character. In common with the times, his spelling was indifferent and his grammar insufficient. But he was proficient in writing and in figures. Form and numbers came naturally to him. In every sense he was a normal and fun-loving boy, but the loss of his father when he was but eleven perhaps increased his seriousness of mind. It was the practical application of what he was learning even in his early youth that stamped him as remarkable. The forms of business transactions, the precepts of correct deportment, as well as his arithmetic, which he pored over at school, were all instructions to him for the conduct of his daily life. In all things he became methodical and was always making plans for future action, whether it was the cultivation of his plantations or the freedom and government of his country. He educated himself to know how to plan and how to do — to be an executive.

A page from young George Washington’s copybook. Photo credit: Library of Congress.

Although the Virginia of the first half of the eighteenth century has many of the aspects of a frontier, constant contact with Europe made it a home of many cultured people. The father of Washington when a boy spent twelve years in England. He sent the two elder brothers of George to Oxford. He might have followed had his father lived. As it was, he had the instruction of an English schoolmaster, and later of a Huguenot clergyman, who taught him the graces of polite society. His youthful copybooks show that he was trained and trained in these things until he became proficient. There was no accident and no miracle, but just hard work.

The death of his father left him with the slender portion that customarily went to a younger son. All about him lay an uncharted wilderness. To bring land under order and law and advance his own fortunes he became a surveyor. His expeditions into distant woodlands in charge of a squad of men, where they must shelter and feed themselves for weeks at a time, the necessity for methodical accuracy involved in the undertaking, were the finest kind of preparation for his future campaigns. He learned how to estimate distance and location and see the military possibilities of wide reaches of country.

Likewise, Washington became a soldier by personal contact and painstaking study. After about the age of seventeen he lived much at Mount Vernon with his elder brother, Lawrence, who had been a captain of militia under Admiral Vernon in the Cartagena campaign and later a major and adjutant general of his district. He placed the young man under the instruction of old army officers who taught him fencing and the manual of arms. So proficient did the pupil become that before he was twenty he was appointed a major.

The same kind of progress accounts for his political training. His father was a member of the Virginia House of Burgesses. His brother Lawrence held the same office. On the great estate below Mount Vernon lived Sir William Fairfax, collector of customs for the district, and president of the King’s council, so that in office he ranked next to the governor of the colony. A little below George Mason had a large plantation. This neighbor was a statesman of great ability and an earnest and consistent advocate of popular rights and local self-government. While these men were somewhat older than Washington, they were his constant companions. When he was but twenty-six he was himself elected to the House of Burgesses. He had to make a campaign to win his seat. His political career began at the bottom. For a number of years he was reelected, and had the opportunity at Williamsburg to take a prominent part in all the political action of the stirring period before the Revolution. No doubt he heard Patrick Henry make that speech which was interrupted with cries of ‘treason.’ During his time he was serving on committees, helping prepare documents and organize associations for the protection of the rights of the Colonies. In very early life Washington came to be a practical politician.

The same background appears in his business training. His father was an important business man, widely engaged in agriculture, mining iron ore, and at times took command of a sailing vessel. In those days there was little division of labor, and each estate was practically self-sustaining. Nearly everything that was necessary for food, clothing, and shelter was produced where used. Disposal of surplus made the planter his own merchant, exchanging his produce in England for what he could not raise at home. Successful operation on a broad scale of such enterprises required a man of affairs. That was the atmosphere of his early home. All through life his decisions were influenced by his great business experience.

When he was only twenty he found himself one of the executors and the residuary legatee of the will of his brother Lawrence. From that time on he had charge of all his father had left him, helping his mother care for her property, and had the management of the Mount Vernon estate of his deceased brother and ultimate ownership of it, besides his duties as major of militia and adjutant general of a district extending over a number of counties. The production of the soil, of the fisheries, of the mill, as well as the supplies for a great many servants and for a considerable force of militia, all passed through his hands.

In general culture Washington must have learned much from Thomas, Baron Fairfax, who came here in 1746 to have oversight of his vast estates which were managed by Sir William Fairfax. He was the holder of an ancient title of nobility, literary, an associate of Addison, a mature man of the world who lived and died a loyalist. He often employed the young surveyor and had him much in his company at his manor house and at his forest retreat. Washington had that rare faculty of being able to absorb what was best in the persons and things with which he came in contact and to disregard the rest. He applied himself to learning and applied his learning to living. He was a disciple of application.

Such was the preparation of George Washington, when, at the age of twenty-one, on the last day of October 1753, he set out to carry a letter from the Governor of Virginia to the French commander, warning him not to trespass on the country around the present city of Pittsburgh. The rest of his life belongs to history.

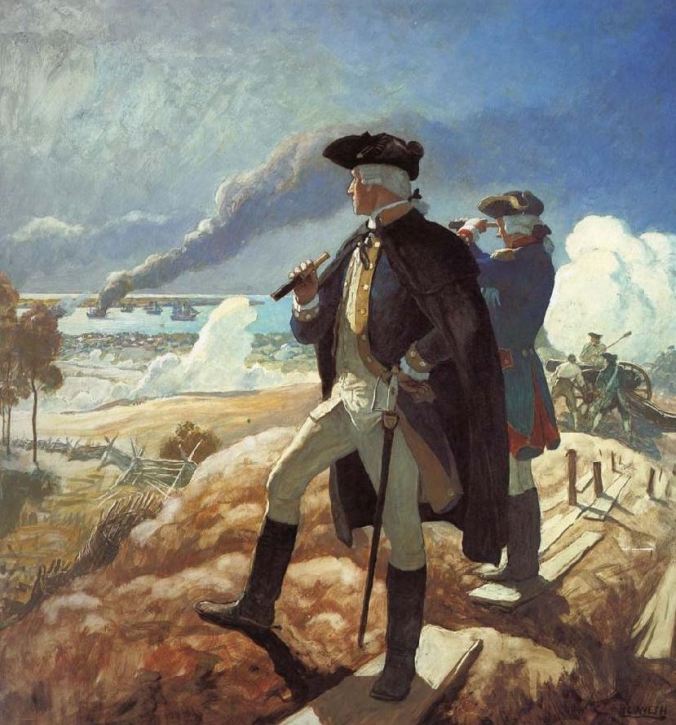

From this time on Washington was a leader in the great plan for the making of America. While New England wanted to be safe from attack from Canada, Virginia and her neighbors wanted to expand into the Ohio Valley. They saw it as a business venture. It was for that reason that Washington was sent to dislodge the French. That expedition started the Seven Years’ War, which finally brought all of North America, except the old Spanish possessions on the south and west, under British rule. The route to the western waterways was opened to the enterprise of settlement.

Washington by Charles Wilson Peale (1772). Colonel Washington was 40 years of age.

Following the end of the war, in 1763, there was a dozen years of agitation concerning the taxation and commerce of the Colonies. As a man of business, responsible for much property, engaged in exports and imports, Washington grasped the full significance of events, and with a deliberation that made his decisions the final word of the people took the patriots’ side. While it is impossible to say that he thus early had a plan for his country that he finally put into operation, it is a fact that all of the plans of consequence thereafter adopted by the country to the end of his life were the result of his approval and support.

When he went to the Congress at Philadelphia he wore his uniform. He knew that the issues meant war and he knew that war meant independence or annihilation. It was his plan for independence, which was for long periods solely dependent on his resolution and military skill, that finally prevailed.

When peace came, turning his attention to agriculture and commerce, he saw that the regions beyond the Alleghenies could only be held by economic ties dependent on transportation. He thought a canal up the Potomac was necessary. That meant the cooperation of several States. When a convention was called for this purpose it was found to be inadequate, and was dissolved, to be replaced by a national convention, called for the purpose of establishing a Federal Government. When it met, not only because he was the leading citizen but the leading nationalist, Washington was chosen to preside over it. The result was a proposal for the Constitution and the Union. As the war could not have been won without him, so the Constitution could not have been adopted without him. The Nation has since been governed in accordance with his plan.

Closer view of Washington, presiding officer of the gathering, from the famous Howard Chandler Christy 1940 Signing of the Constitution.

It is one thing for a people to go through the form of adopting a constitution, but it is quite another to put it into successful and permanent operation. Our form of government was new to human experience. All the rest of the world thought it could not last. It was inevitable and absolutely necessary for Washington to be made the first President. Without his ability, his prestige, and his character, it is probable our Government might have broken up before it had a fair start. He made it a success because of his firm belief in the principle of government. He had had enough experience so that he knew the necessity of exercising all of the sovereign authority which the new Constitution provided. But his plan was for the exercise of the authority which the people themselves had created. His constant desire was to administer their Government.

Too little emphasis has been placed on his faith in a government of the people. When in the confusion and bankruptcy of the closing months of the Revolution, the Army started a movement to make him king, he promptly denounced it. He wanted a government of the people, but he wanted it to be a real government capable of governing. Law and order were his gospel. He sympathized with his soldiers and the people in their distress and sought to relieve them by legal means, but he would fight usurpation of a mob as readily as usurpation of a monarch.

When he took office, the most pressing requirements of the new Government and the people were financial. It was here that the sound business experience and the judgment of Washington were of supreme importance. He knew how to deal with questions of taxation, commerce, and credit. For working out the details he had Hamilton as his Secretary of the Treasury, but his were the final decisions.

Washington depicted taking the Presidential oath of office, March 4, 1789, Federal Hall, New York. He was 57. Photo credit: National Park Service.

To provide funds, import duties, and internal-revenue taxes were levied. When some people in Pennsylvania resisted payment with force the Army was sent to execute the law. The debts of the States, contracted for national defense, were assumed. To facilitate the operations of the Treasury in collection and disbursing funds and maintaining credit operations a national bank was established. His policy was to strengthen the National Union sufficiently to make it a complete reality without encroaching on the States. He had seen enough of the futility of a government without authority when he commanded the Army.

His foreign policy was independence, peace, justice, and neutrality. Public clamor could not induce him to become involved in the French Revolution. He signed the treaty with England that was at first so unpopular and made a treaty with Spain, opening the Mississippi, because he knew both were beneficial to our commerce.

Wyeth’s portrait of Washington

Finally, he summed up his political creed in his Farewell Address. He believed in liberty and the Union unhampered by national jealousies. He urged respect for authority and obedience to law. Education, religion, and morality he considered necessary supports of free institutions. Careful maintenance of the public credit by a sparing use of it, impartial justice to all nations, permanent alliance with none, and adequate national defense were some of the important points in the wise plan for future action which he presented to his countrymen.

Washington had a deep understanding of human nature and a profound loyalty to the truth. He had the best political judgment and was the best soldier of his time. His permanent success as a statesman was due to his ability to apply business principles to political needs. Our country has never made a mistake when following his counsel.

Happy Birthday, Mr. President!

My Beloved Country — George Washington, based on the Houdon sculpture, oil portrait by Igor V. Babailov. Photo credit: Igor Babailov.