The path to the White House has, from the very beginning, been a varied and extraordinary one. Who would have thought in the spring of 1754 that a tall 22-year old redheaded soldier in the deep woods of Pennsylvania would one day become President of the nation in which he was standing? Who would have realized he was about to start a war too? Even the term President as the head of a country would have boggled the mind. There has been no single gate through which our Presidents have all passed to equip them with the qualifications needed or the character the Office always brings out of the individual. Whether or not the temperament and abilities were evident beforehand, circumstances always arise that require previously unknown reserves of skill and judgment. If they are lacking, people find out pretty quickly and work to correct the mistake of leadership. At crucial times, the completely unforeseeable situation brings the leader to a crossroads and either he rises to meet events better than anyone could have anticipated or his limitations exacerbate the indispensable and constant need for good leadership.

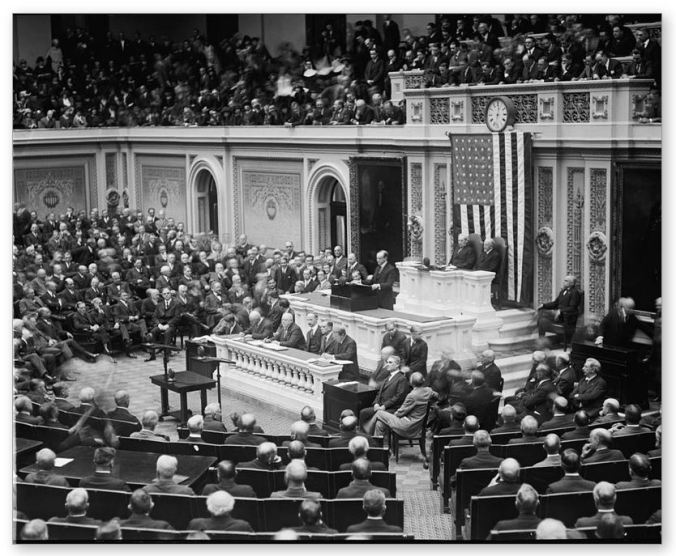

Congressmen do not always make good executives. They have produced, arguably, some of the worst. Who considers Pierce’s and Buchanan’s time in Congress as improving their talents as Presidents? Who regards Ben Harrison’s six years in the Senate as helpful toward preventing the first Billion-Dollar Congress, during his Presidential tenure? When President Polk (“Young Hickory”) asked former President Jackson (“Old Hickory”) in 1845 why he objected to Polk’s selection of the patrician James Buchanan as the new Secretary of State after Jackson had appointed Buchanan U. S. minister to Russia back in 1832, the old President replied, “It was as far as I could get him out of my sight. I would have sent him to the North Pole if we had kept a minister there!” John Quincy Adams, similarly, posted William Henry Harrison to Colombia in 1828 not because he was necessarily qualified or useful there but to get the old General off his back about a job. Governors do not always make effective Presidents either but it can certainly help. Look at Polk and Cleveland, Coolidge and FDR. Training in the legislative halls of the federal government has become a favorite approach, though, to the White House. Twenty-five Presidents have been a member of House, Senate or both. Four of those were also past governors and state legislators (William Harrison, Tyler, Polk and Andrew Johnson). In Andy Johnson’s case, his past experience as a legislator did little to commend him to the boys on Capitol Hill. He would be vindicated by election to the U. S. Senate after the Presidency. Only one (John Quincy Adams, never the type to follow the conventional) commenced a legislative career after his time in the White House.

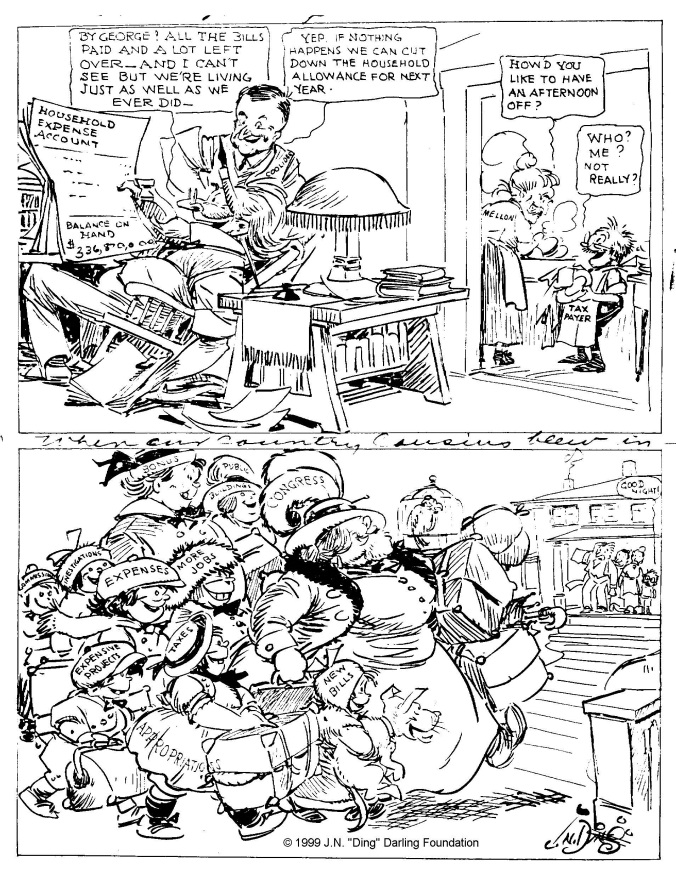

The function and dysfunction of Congress gives the future Chief Executive a bearing on the process of national legislation. This is not always a useful perspective, tending to soften Presidents to a mentality given to over-legislating, passing responsibility or even just looking the other way while Congress appropriates what should not be spent. This is what Coolidge calls “the political mind…the product of men in public life who have been twice spoiled…spoiled with praise and…spoiled with abuse. With them nothing is natural, everything is artificial.” Few, Coolidge would observe, escape these influences and keep a clear vision and unimpaired judgment. While most would likely agree that Lincoln’s objectives rested elsewhere, he did little in the way of checking Congressional tendencies. He certainly knew how to use them to his advantage, including his adversaries. When Johnson exhibited a different outlook, the political mind in Congress retaliated in grand fashion. It would do so again with Nixon and Ford.

Look again at Polk, whose work as a state legislator, Governor, and finally Speaker of the House sharpened his focus, accomplishing all four of the goals he set out to achieve in a single term as President. Few indeed share that rate of effectiveness. Of course, Grant would disagree, in the long-term, that the issues of the Mexican War resolved successfully. Wresting California from Mexico has not quite yielded entirely congenial results, all things considered. Had Grover Cleveland been a legislator instead of an executive, he might not have been so determined to roll back the favorite legislative pastime of opening the public Treasury as far and wide as it can go. The only county sheriff and one of three Mayors to become President, New York Governor Cleveland not only rose with meteoric speed (from Sheriff to President in fourteen years) but hit the ground running and, while the vetoing slowed in his second term, it never flinched. On the flip side, how different might LBJ’s career have gone had he not been nursed on federal employment from age 27? Or, how different might things have been if JFK and Nixon started, not in Congress, but in town councils and state houses?

John Adams and Thomas Jefferson came to it through the Vice Presidency after crucial experience in the Continental Congress. Jefferson, though, was the first to occupy a Governor’s chair. Nineteen Presidents have followed in his steps, including some of the best known, TR and Wilson, FDR and Reagan, Clinton and Bush 43. There is still something to be said for starting at the state and local level. Thirty-five Presidents started there, headed by Washington himself. Coolidge explains why this is important,

It is axiomatic that half the world does not know how the other half lives. But state legislatures are fresh from the people. They know the conditions of their own neighborhoods much better than Congressmen know them. Some people are suffering from lack of work, some from lack of water, many more from lack of wisdom. These facts have been emphasized all out of proportion to their importance. Other facts of abundant supplies of food, raw materials, credit, productive capacity and the ability of a free people to take care of themselves when necessary being almost entirely ignored. Cities and towns are responsible for relief. Give them all needed authority to raise and expend their own money for that purpose. That and local charity will be sufficient. Recall the principle of President Cleveland that it is the business of the people to support the government, not of the government to support the people. We can supply enough of our own lack of wisdom. We do not need to increase it by unwise legislation.

Cal remained acutely skeptical that federal office truly endowed the best training ground for faithful public service. For him, the liabilities always outweighed the advantages. He would come to see that most federal employees were faithful and conscientious, who deserved great regard for their sacrifice and dedication but even there, it still did not mean Washington was the best place for preparing our Presidents. For all that could be claimed about local provincialism, it had a far better gauge on what neighbors faced and needed than an oft timid House and Senate understood. Or, than Washington’s #1 industry — organized interests — could comprehend. Too many instances of spoiled goods came out of the U.S. Capitol. The exception, not the rule, was wise statesmanship. He saw it this way,

The government has never shown much aptitude for real business. The Congress will not permit it to be conducted by a competent executive, but constantly intervenes. The most free, progressive and satisfactory method ever devised for the equitable distribution of property is to permit the people to care for themselves by conducting their own business. They have more wisdom than any government.

A legacy of sound measures really didn’t come from Congress. As Coolidge would see, we need not look far for a dismal track record: Just look at how Congress runs things in its direct jurisdiction, the District itself. The place was replete with men and women who started well but D. C. eventually ruins even the best. No one was infallible, a government official at any level, least of all. But, for Coolidge, the errors at the national level were always so much costlier, multiplied unintended consequences so much wider, and had the effect of spreading a contagion as opposed to quarantining it. A fleet of trucks could drive with ease through the mistakes made by Congress, having as it does vast authority without parallel responsibility. With so many chiefs and so few Indians, it is what makes the Presidency — not the Congress — the representative of the whole people in a way House and Senate never will be. That was the beauty and wisdom of reserving powers to local and state government, it helps contain disasters instead of nationalizing them. Why spread a blunder upon everyone before it has had time to prove what works and what does not? Coolidge saw the better part of valor and greater share of virtue did not rest with an approach that all be forced through a uniform, one-size-fits-all system. No majority could make it wise and no organized minority could be trusted either. If a measure was sound, it should prove itself locally first but we would do no one any favors by compelling everyone to adopt X, Y or Z, because an organized minority in D. C. wants it so. This is a principle even co-opted majorities can trample. Its continual encroachment threatens to enthrone a regime where the political rights of the most populous centers steamroll all others’ rights and interests.

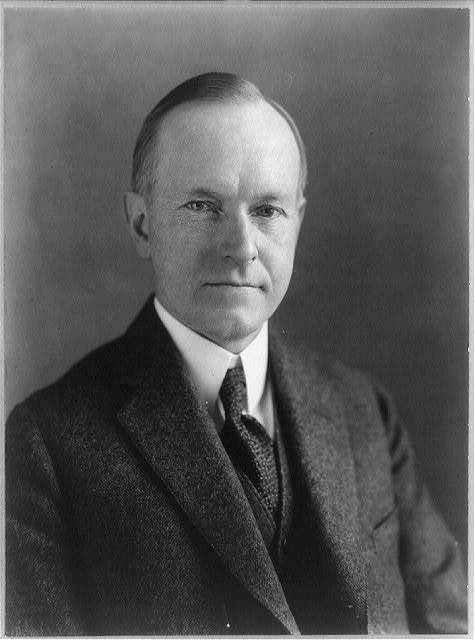

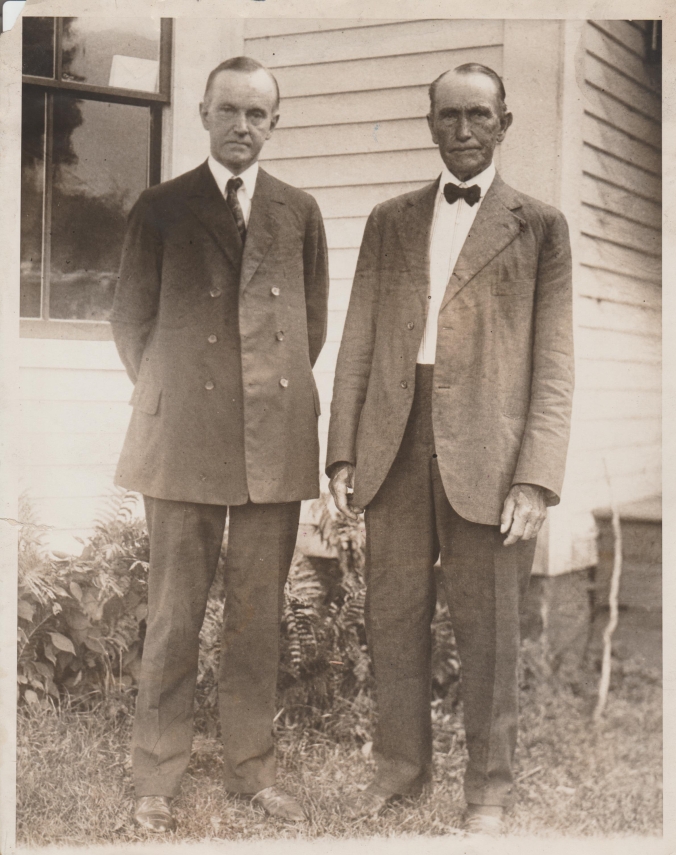

Coolidge with his father, Colonel John, who had served Plymouth Notch and the surrounding area as a Justice of the Peace, state legislator, storekeeper and just about everything in between them. This has been a heritage shared by most of our Presidents.

Stripped of all disguises, it was merely another variation on the tyranny of might making right, enshrining the vote of a majority above the considerations for every weaker partner in society. The same safeguards between states and D. C. were likewise meant to function within each of the states as well. Not every state would venture out on wisely laid plans or carefully considered actions any more than Congress would. Coolidge saw how vital it was that the mistakes of states not immediately infect their towns too. The localities were like “water-tight compartments,” he said, “in the ship of state.” If we opened everything and demanded uniformity, we would all very quickly end up underwater. It made such irrefutable sense to him, he could not see how anything but a suspension of sanity could entertain sinking the whole vessel to learn whether the bill was a bad idea or not. That was why, as he encouraged his father in the state legislature,

It is much more important to kill bad bills than to pass good ones.

Even the most vital legislation was subordinate to keeping the bad stuff from slipping through the cracks. What the legislation said was everything. It was not to be cavalierly thrown together with high hopes and best wishes that it might work out in the end after passage.

See that the bills you recommend from your committee are so worded that they will do just what they intend and not a great deal more that is undesirable. Most bills can’t stand that test.

This was also why passing “one piece of legislation at a time,” however often Congress flouted that principle, “is most salutary. It prevents crowding through measures that the majority does not favor and forces all bills to stand on their merits.” He could have also said: “Most bills can’t stand that test” either and he would be right. But then, that is why Congress routinely does it. Nor was he worried that the good would languish with time, on the contrary, there was a vital protection to liberty in deliberation,

A good measure can stand discussion. A bad bill ought to be delayed…To give a check upon the popular House of Representatives the Constitution established the Senate to be more permanent, independent and conservative. The House was to protect the people against oppression. The Senate was to protect the people against disorder…If they [bills] have real substance the people respond. Of course the power to debate can be abused. But it is safer to employ those who abuse power in debating than in voting. Open debate is the only shield against the irretrievable action of a rash majority.

And there has indeed been too much “legislating by clamor, by tumult, by pressure,” he noted. The representative is neither a marionette nor a autocrat, but expected to weigh every matter “most carefully” and in accordance with the oath each takes. It is an oath not to a governing body but to the Constitution and the laws. That Constitution still requires a quorum, an actual vote, and the barest responsibility that putting one’s name on the record entails. As Coolidge declared in one of his gubernatorial vetoes,

I am opposed to the practice of a legislative deception. It is better to proceed with candor…My oath was not to take a chance on the Constitution. It was to support it. When the proponents of this measure do not intend to jeopardize their safety by acting under it, why should I jeopardize my oath by approving it? … There can be no constitutional instruction to do an unconstitutional act.

They would best learn the practical realities not from a textbook or up in D. C. but closest to their source: small town America, where the little people live, work, and face the decisions, good and bad, made by their representatives. Here was ground zero for the most fundamental operation of government and citizenship. It was here that public office as a public trust lived and breathed most vibrantly. Bad government could thrive too but not under a good and watchful citizenship. Bad citizenship always preceded and perpetuated bad government. It was here that the cause and effect of the people imposing obligations on themselves through chosen representation could be most clearly seen. It was here that each one could learn in the finest academy of practical life what self-government means and how it should work.

When you substitute patronage for patriotism, administration breaks down. We need more of the Office Desk and less of the Show Window in politics. Let men in office substitute the midnight oil for the limelight…

It is necessary to watch people in Washington all the time to keep them from unnecessary expenditure of money. They have lived off the national Government so long in that city that they are inclined to regard any sort of employment as a Christmas tree, and if we are not careful, they will run up a big expense bill on us.

Doing something for effect gained nothing in Coolidge’s eyes. He had no use for it. He also knew Washington for what it was. He was under no illusions and, after almost thirty years in public life, he still, thankfully, could not get used to it.

I never knew such meanness existed in the world as I listened to in Washington…nearly every man who came was seeking something–either office or legislation he desired enacted or defeated. Few came to urge measures or men for the public good–though nearly all professed it. I had some experiences of that kind, of course, in other executive positions, but I was not prepared for so much of it and with so much persistent under-cover pressure. It seemed strange to me that a President, if he is to avoid mistakes, has to suspect and resist almost every suggestion from callers until he can look into it most searchingly–and then usually ignore it. Some of my visitors, after leaving the White House, criticized me to others for my silence. If they had known my thoughts while I listened to them they would have praised me for not speaking.

As Coolidge confided these impressions to Henry Stoddard from rocking chairs on the porch at Plymouth Notch in retirement, Stoddard would recall that D. C. had left almost exactly the same response from those Presidents Stoddard had known personally and “through the experience of all our Presidents.” McKinley had told Stoddard almost verbatim the same thing. A story had widely circulated of Wilson who exclaimed that the hardest job of the President was to restrain his temper in the presence of callers who ask for what they should not have. From Harding, when a judicial nominee came up for consideration with glowing recommendations from lawyers back in the district, he was told, “Every endorser on that list knows that this candidate is not qualified…Herd-like, they signed up. They wanted to be with the winner…I insisted, however, upon publishing the names [of the endorsers] or dropping the candidate. Within a week a number of endorsements were withdrawn…and a competent judge was later appointed.” Hayes, undergoing a much less congenial relationship with Congress, would confide to his Diary: “It is no doubt well to leave the high place now. Those who are in such a place cannot escape the important influence on habit, disposition and character. In that envied position of honor and distinction they are deferred to, flattered and supported under all circumstances, whether right or wrong by shrewd and designing men and women who surround them. Human nature cannot stand this too long!” It was what Coolidge would explain in a later day,

The President has to remember that he is dealing with two different minds. One is the mind of the country, largely intent upon its own personal affairs…Those who compose this mind wish to have the country prosperous and are opposed to unjust taxation and public extravagance…The immediate authority with which the President has to deal is vested in the political mind. In order to get things done he has to work through that agency. Some of our Presidents have appeared to lack comprehension of the political mind. Although I have been associated with it for many years, I always found difficulty in understanding it. It is a strange mixture of vanity and timidity, of an obsequious attitude at one time and a delusion of grandeur at another time, of the most selfish preferment combined with the most sacrificing patriotism. The political mind is the product of men in public life who have been twice spoiled. They have been spoiled with praise and they have been spoiled with abuse. With them nothing is natural, everything is artificial. A few rare souls escape these influences and maintain a vision and a judgment that are unimpaired.

This same political mind would almost convince Cleveland to throw up his hands and resign. It would compel Reagan to declare, “We are a nation that has a government — not the other way around.” It would persuade Eisenhower to write in his Diary, “We can afford to have only those people in high political offices who cannot afford to take them. Patronage is almost a wicked word–by itself it could well-nigh defeat democracy.” It certainly took the first shot at an otherwise young and promising James Garfield, if not others.

The abundance of artificiality, obfuscation, and calculated cynicism dilute the strength of those needful lessons in what is real from what is fake. In those timid hours, Congress regularly succumbs to organized minorities, what Coolidge would call “a well-recognized industry at Washington.” This is precisely why:

The President comes more and more to stand as the champion of the rights of the whole country…If it were not for the rules of the House and the veto power of the President, within two years these activities would double the cost of the government.

And yet, through all his skepticism about the limitations of Congress, he preserved a healthy perspective there as well. He knew that the sum total was only as good as the material sent to it from the various states. It could not be greater than its parts. If people didn’t like a particular direction or style, it was only because each house and the President had to work with what voters sent them. Therein rested the enduring call to be better citizens ourselves if we want better government. It was not the fault of the institutions but an obligation to demand more at the ballot box. There was the power and the duty. In addition, Coolidge enjoyed one of the best relationships with Congress of any President, despite its awkward and often recalcitrant disposition, then and now. This was possible without having to be, as Harding had, one of them. Coolidge could do this by letting Congressmen do what they do best: talk. By playing on their strengths and a certain rivalry between House and Senate, he found an unwise action usually corrected itself either on the floor or during consideration in the other chamber. Coolidge found the parties were not detrimental but had a useful role in the process and “most of the differences could be adjusted by personal discussion.” But he could curb the political mind by appealing to the country, directly or indirectly. It came with a caution, however.

A President cannot, with success, constantly appeal to the country. After a time he will get no response. The people have their own affairs to look after and can not give much attention to what the Congress is doing. If he takes a position, and stands by it, ultimately it will be adopted.

Coolidge did not have to point to some other President’s experience, he knew it to be true in his own case.

Most of the policies set out in my first Annual Message have become law, but it took several years to get action on some of them.

By taking his reminders to millions of listeners on the radio or in a gentle suggestion dropped here and there as needed, he could get more out of Congress than they thought possible. He was no pushover. He understood its constitutional role better than Congress comprehended the Executive, checking its attempts throughout his tenure to intrude on Presidential prerogatives. Appointments were his own, not perks of Congress, and foreign policy belonged where the law had placed it — with his Secretary of State and the diplomatic corps. The Senate’s presumption that it could set course above the head of the President, discovered this was no novice to be sidestepped or coerced.

A convenient distance, afforded even now by optics, screens the potency of the political mind. Congress is too often far downstream of the source for countering that mindset with the mind of the country. A generous dose of the latter is the best antidote to the former. The culprit is not necessarily starting our Presidents on a path that begins with time in Congress, though it was what made permanent enemies for Nixon and Ford. The problem is how to avoid sustained exposure — with all the harmful effects — if not to find a cure altogether for the political mind once it has been contracted. It is that mind that is the real threat to life and health, whether or not a President ever steps foot in Congress. It is, nevertheless, the Congress which has the most concentrated degree of it.

It is difficult for men in high office to avoid the malady of self-delusion. They are always surrounded by worshippers. They are constantly, and for the most part sincerely, assured of their greatness. They live in an artificial atmosphere of adulation and exaltation which sooner or later impairs judgment. They are in grave danger of becoming careless and arrogant. The chances of having wise and faithful public service are increased by a change in the presidential office after a moderate length of time.

With one notable exception (FDR), most of the Presidents who started in some local office, kept faith with that custom, now codified in the Twenty-Second Amendment. Of course, it was not always by choice, like it was for Polk. Sometimes the political mind of Washington shut that door for them, as in the case of Tyler. Other times, the people themselves believed it best to send the President back home, as occurred for Adams (father and son) along with Carter yet their legacies endure well beyond their short stays in the White House.

This is both a Presidential election year and a Census year. The political mind thrives in such conditions and Congress, ever animated by its allure, opens again the Treasury with delight. By partaking of a different mind, however, wise legislation will result. It will not come by resorting to, indulging in, topping up the insatiable appetites of those in public life “twice spoiled.”

I am not one of those who believe votes are to be won by misrepresentations, skillful presentations of half-truths, and plausible deductions from false premises.

The political mind, with its alternating penchant for going cheap or going broke, will not yield a good crop. Every decennial census up to 1920 had seen representation grow accordingly but that ended the summer after Coolidge’s departure from Washington. The ability of Congress to adequately represent constituencies, which had finally tipped to an urban majority in 1920, was undermined still further ahead of the 1930 census when membership was capped by the Permanent Apportionment Act of 1929, signed by President Hoover that June. For those honest with themselves, the practical realities of responsible citizenship and good government come from the streets, towns, counties, and states or they do not come at all. They, not Congress left to itself, will provide whatever good can come from a stimulus bill. While Coolidge would agree that Jefferson left much to be desired as President,

This does not detract from the wisdom of his faith in the people and his constant insistence that they be left to manage their own affairs. His opposition to bureaucracy will bear careful analysis, and the country could stand a great deal more of its application. The trouble with us is that we talk about Jefferson but do not follow him. In his theory that the people should manage their government, and not be managed by it, he was everlastingly right.

It was in the countryside, streets, towns, counties, and states where Washington through Monroe first earned public trust. It is notable that Washington had more than double the years of experience in a legislature than any of the others, even the democratic Jefferson. It was likewise where fifteen more future Presidents first represented their neighbors, Andrew Johnson beginning as a city councilman and mayor before heading to the state capital. Jackson would not serve in a state legislature but he began as an attorney general in western North Carolina. Van Buren began as a county surrogate then a state senator and New York’s Attorney General before rising to Governor. Coolidge began as a city solicitor, Truman as a county judge. Fillmore, ever close to his roots, came back to them repeatedly through his career, serving as Comptroller for his state after two stretches in Congress. A favorite illustration of weak and ineffective Presidents, it was actually Fillmore’s strength in dealing with Congress that cleaned up the mess left by his predecessor (Zachary Taylor) and postponed the bloodiest confrontation in our history by another ten years. It was his connection to and affinity for local self-government that first equipped him, however, and earns him more respect than he typically receives. Few of the fifteen served more than two terms, Lincoln (the foremost exception) putting in eight years in the Illinois General Assembly. By doing well in small things, they were entrusted with greater things. Not all succeeded but all gained what Congress alone could not impart. At times they would brush with other future Presidents, Manhattan’s Assemblyman Theodore Roosevelt with Governor Cleveland, a notable example. President Hayes’ removal in 1878 of Customs Collector Chester Arthur is another.

Of course, overlap in Congress among future Presidents abounds. Madison and Monroe may have been the first to serve in House and Senate during the same years but they were by no means the last. The 1820s would bring six future Presidents into Congress in close proximity of time while the 1830s would usher in two more pairs. Lincoln and his future running mate, Andrew Johnson, would serve together in the 30th Congress, Hayes & Garfield in the 39th, and Garfield & McKinley in the 45th and 46th. The most significant instance would be between 1935 and 1971 when no more than six future Commanders-in-Chief shared seats in Congress, at various times in that thirty-six year span, with at least one other POTUS-to-be (Truman, LBJ, Kennedy, Nixon, Ford and Bush 41). But the diverse portfolios of those who served their country by first serving their towns and localities deserve greater recognition than they normally receive. The second half of the twentieth century, especially after JFK, saw a slow departure from that priority. Four of the next seven had not really gotten feet wet at the small town, low-key, Main Street level and, it could be argued, America definitely suffered for that deficiency. Looking back on his twenty-nine predecessors, as of 1929, Coolidge could say,

Although all our Presidents have had back of them a good heritage of blood, very few have been born to the purple. Fortunately, they are not supported at public expense after leaving office, so they are not expected to set an example encouraging to a leisure class. They have only the same title to nobility that belongs to all our citizens, which is the one based on achievement and character, so they need not assume superiority. It is becoming for them to engage in some dignified employment where they can be of service as others are.

To some useful work for the benefit of others, then, was Coolidge’s own ambition. Surely Carter has embraced that enthusiastically. It has been Carter’s post-Presidency that has largely redeemed him. Like #39, Cal did not wish to retire unto idleness and privilege. It is evident he would disapprove of what the political mind has done toward the creation of a class of American royalty with its Presidential pensions, publicly-funded support staff and a tax burden that, of course, Congress sends down to us. There had been patricians before (with names like Harrison and Tyler) and there would be more to come (with names like Roosevelt and Bush) but they were a distinct minority and even some of them would start life quite literally inside roughly-hewn log walls. It would be a beginning shared by no less than nine Presidents (Jackson, Polk, Taylor, Fillmore, Pierce, Buchanan, Lincoln, Johnson, and Garfield). Simple farmhouses would greet John Adams, Warren Harding and Harry Truman. A room in back of the country store would welcome Calvin Coolidge. A small apartment would receive Ronald Reagan. Grant and McKinley would be born in modest rentals. They would each build on those most American of beginnings with indispensable preparations close to home. They would not come to Washington as clean slates looking to take their first job or step out on their own but because they had already proven themselves in some capacity among the folks back home. Whatever they might do with that preparation, they had first shown themselves worthy in the little things.

British burn the Capitol, 1814, by Allyn Cox.

We deprive ourselves of that advantage when we repose confidence in those who have never faced the test of a small scale job and done it well, rewarding them too quickly with big tasks and prestigious positions. The political mind, convinced of its own greatness, would promote candidates not fit to be dog catcher. This tendency is a dangerous one. So is the precedent of Presidents camping in Washington once they retire, as Wilson would in 1921. The “professionalization” of politics that gets shaken up from time to time by a Jefferson or Jackson still labors to kill a beast that never truly dies. In our urbanized America, not even the executive management of a farm is much of an option anymore for those who need to learn to oversee something smaller than the federal budget before they get thrown into making internationally impactful decisions at age 30. We are once more ominously near a cradle to grave federal job rotation system with Congressional sessions that still operate in the crisis mode of 1941, raising all too many future leaders for a life that barely requires living in the world that exists beyond Washington and would still be there if the British ever paid us a favor and decided to again torch it.

Whatever may be said of the most effective course in public service, all four individuals carved into Mount Rushmore began in a local office of their county or state. There must be something to those little cradles of self-government, the watertight compartments of towns, counties, and states that the fed obviously benefits from but for which it cannot claim credit for creating…or maintaining. The Presidency, like everything else, is constantly changing but some principles remain, including Coolidge’s reminder. The more often we draw from that well, the better the results will be for America.

We draw our Presidents from the people. It is a wholesome thing for them to return to the people.