“It lays on society first, the necessity in behalf of the general welfare of supporting and defending our institutions, and in the second place of striving diligently for their practical improvement. The ground for optimism lies not in the fact of past or present perfection, but in the hope and belief that progress has been made and will be made, in spite of many calamities, and many seeming disasters, which at present appear inscrutable to the understanding of finite beings.

“The soundness of this position I believe is demonstrated by history, and the justification of those institutions, so typically American, here so resolutely adopted in the beginnings of this state, and ever since so stoutly maintained, if made at all, will be made out of the knowledge of past human experience. It is this which preeminently justifies the study of history and the formation of Historical Societies. It is by an understanding and comprehension of the past that we judge of the present and the future.

“History is to be studied and applied not for the purpose of advocating reaction. It is not the accurately informed who continually appeal to the good old times to the disparagement of the present. That is characteristic of those who substitute fable and hazy tradition for fact and reliable record. True history which includes all the records of the past, however obtained and wherever recorded, whether made upon the surface of the earth by the ceaseless shifting of air and water, or transmitted by written signs on tablet or parchment, or through oral repetition handed down from sire to son, or that most indelible of records the accumulated experience of generation after generation, moulded into the brain of man, while ever a conservative force, yet holds the only warrant for real progress. It is ignorance of its teachings, which leads men of good intentions to advocate either reaction or revolution, and a knowledge of its forces, which aids men to promote the public welfare. In judging of the strength of a state it is necessary to know what has gone before, what point of development has been reached by the people of that state, and whether their present plan of society is justified by their past experience.

“States grow and there is an inexorable law of their growth. They must go through the process step by step. There is no hiatus in their development. Liberty is not bestowed, it is an achievement, but it comes to no people who have not passed through the successive stages which always precede it. It is very far from a state of nature. It is no light and easy thing to secure or to maintain, but difficult of accomplishment and hard to bear. While there are no conditions under which it is better to be a slave than to be free and for the sake of their ease there are those who have chosen to relinquish much of liberty rather than bear the responsibilities of the free. The greatest example of this was the development of feudalism in the middle ages. Men sought their security and protection at the expense of their freedom of action, so that whole communities were bound to varying servitudes which reached from honor to infamy, yet all with the same object, their greater ease and safety. While such a state has seemed to delay progress it really resulted in weeding out the incompetent and developing those who had the capacity to advance.

“The process of each state in government has been from unorganized races to the despotic rule of an absolute monarch, which in time became limited and its functions shared in by a nobility, gradually enlarging into some form of parliament, and finally extending to all the people. There have been many grades and forms of such development under many and various names, but the process has ever been from anarchy through despotism to oligarchy which has broadened out into democracy, and ended in representative government, based on universal suffrage.

“Many nations have failed somewhere along the way. The absolute monarchy has fallen into weak or vicious hands so that disorder at home or some superior force from abroad has overcome the State. Or a people have seemed to lack the genius for government, or a strong king has overcome a popular assembly, and what at one time appeared to be free institutions, administered by a legislative body with generous powers, as in Castile or Aragon at the beginning, and in France at a later period, of the Middle Ages has lapsed back to despotic rule.

“It is interesting to note that no nation ever lost its liberties in which there was maintained a strong representative body vested with the authority of providing the public revenue. It has been suggested that Spain was able to disregard the liberties of the people because her rulers became so enriched by the revenue of the new world that they no longer had need to call on the representatives of their subjects for funds but had ample means to provide an army which overawed the people and finally made the Spanish monarchy absolute.

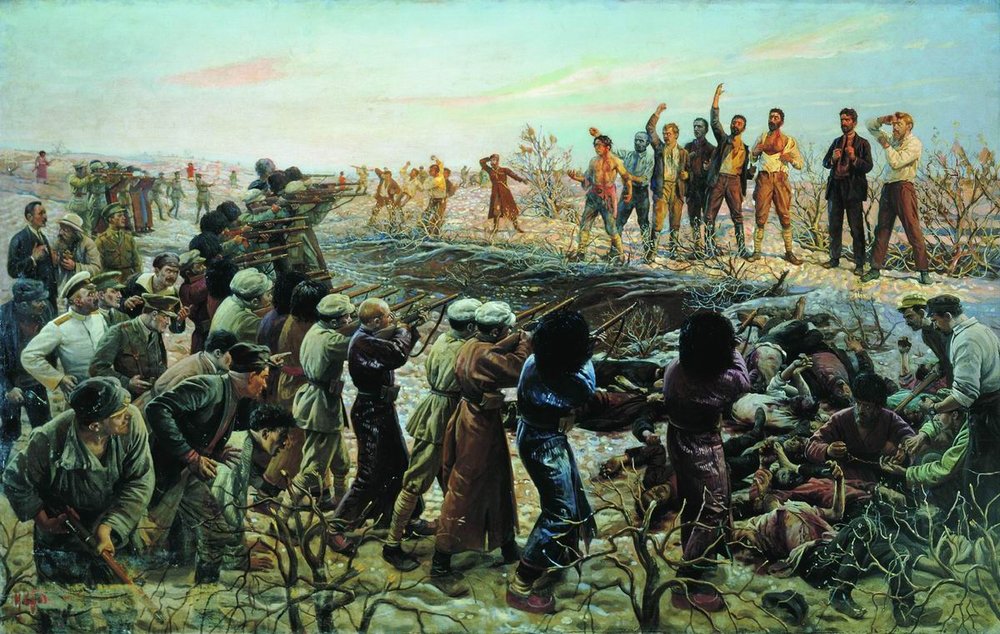

“When the French people at the time of their Revolution summoned the state’s general, after a period of nearly two centuries of absolute monarchy, and attempted to step at once into a republic, of course they failed and landed in a new and worse despotism than that which they threw off. In our own day we have seen a like result in Russia. There is a step between absolutism and a republic which cannot be avoided in the experience of a people journeying toward popular sovereignty. Russia, with all the examples of the free nations before her, is under a despotism more despotic than ever was administered by a Czar. Russia and France, failing to reach at a single bound the form of government they sought, fell back into disorganization which is always the opportunity for the despot.

“There is a certain amount of ground for faith in progress in the fact, that apparently there could have been no other means to break the despotic hold of the Bourbons of France, so that she might finally emerge after the chastening experiences of sinking from world glory to humiliating defeat under the Empire of Napoleon; she emerged free, a republic, and with a strength of character and a power of resistance which has restored her to a true glory in the estimation of the world which no nation ever outranked. In her example there is hope for stricken Russia. Evidently she reached an impasse in her progress which threw her people back on the first principles of development. Lacking the advance of France in the late days of the eighteenth century, she will lack her speed of recovery. But modern science is on her side if she will but use it. Who now can say what service to progress Lenin and Trotsky may not be performing when he remembers the Three Furies of the French Revolution?

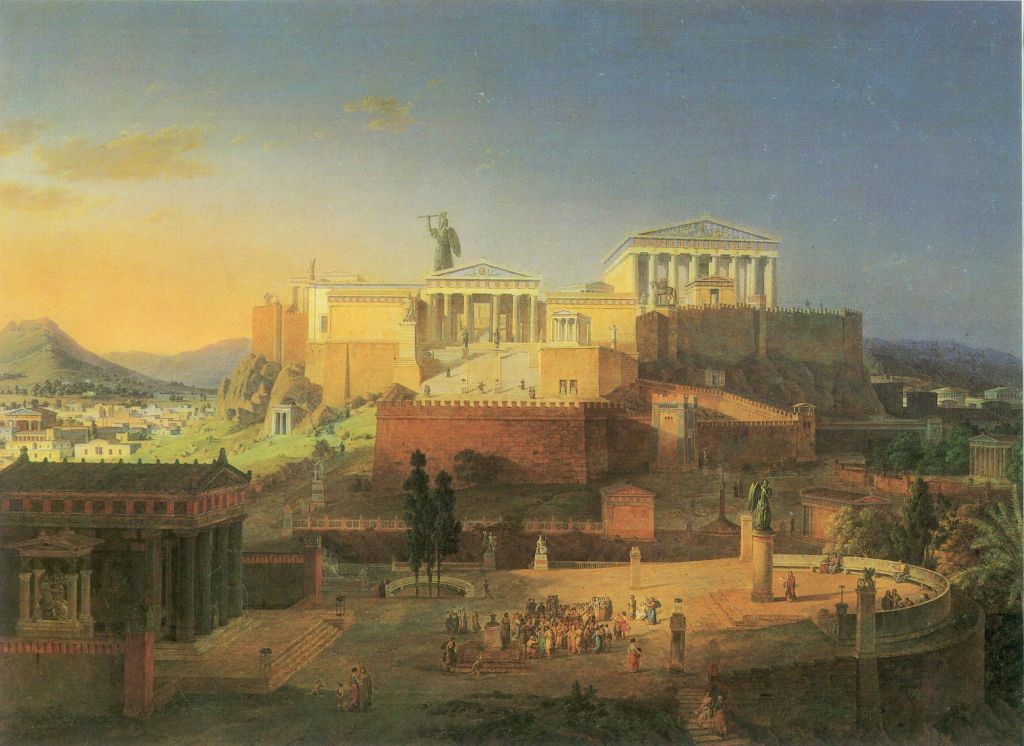

“Always before we decide too hastily that the decline of the nations of antiquity constitute a total loss, it is well to examine what was destroyed and what was saved. The ancient civilizations which flourished along the Nile and in the valleys of the Tigris and Euphrates ran their courses. They performed their tasks and went the way of all the earth. Modern scholarship is revealing to us, year by year, the completeness of their organization and the high attainments of their civilization. They were not destroyed in a day but grew up, flourished for a time, and gradually, as their work was taken up by the Greeks, Babylon and Thebes, passed into obscurity. A stronger took their place. Through the long generations that marked the decay of Greece, after the Macedonian subjugation, the real strength of that most wonderful people remained, remains to us today in the priceless treasure of her arts, the richness of her literature, the deathless eloquence of her orators, the wisdom of her statesmen and the inspired insight of her philosophers. The great lesson of the supremacy of the state and the art of government is so much hers, that it is impossible to discuss the forms and methods of government without drawing from the Greek for the very nomenclature with which to express our thoughts.

“When the scepter passed from the Acropolis to the Forum it meant that men had progressed to that point, where it was necessary for the advance of civilization, that they should come to a realization of the law. That is the supreme meaning of Rome. For centuries she imposed the rule of order under law, often harsh and cruel, yet with such a meaning of restraint, that Roman citizenship was respected and reverenced at home, and held in such awe abroad, that in the days of Saint Paul he had but to assert it, to confound his persecutors, and fill them with the dread that swift and unerring punishment, which befell those who treated with any indignity a representative of that empire which ruled the earth, making a peace longer than has ever since blessed mankind, known as the Pax Romanum. When under the march of her legions the people along the Jordan and at Jerusalem lost their independence and began to be scattered throughout the earth, the Ark of the Covenant and the seven-pronged candlestick passed from the knowledge of man, but the Old Testament remained, rearing multitudes of temples more magnificent than that which fell to a plundering and alien conqueror.

“The forces of the Roman Empire became set. Their plasticity ceased. They lapsed into a condition where they made no progress. The power from within having been exhausted, the only hope lay in an infusion of a power from without. That came with what has been styled the barbarian invasions, intermittent, closing down in darkness at first but finally rousing Europe to a new birth which ushered in the modern period of history.

“Nowhere did the shock of these continued invasions beat more steadily than around the shores of the North Sea. Parts of Britain and Northern France, which had been under the discipline of Roman law, bear to this day the names made by their invaders and conquerors. It was there that free institutions developed according to the true form from the iron rule of William the Conqueror to the Commonwealth of Oliver Cromwell. Without haste but without delay, that process has gone on in government from the days of Babylon to the days of the Constitution of Vermont. Our people have come and lived, and solved one problem, and when they have ceased to function successfully, another people have taken up the burden and borne it forward.

“Coincident with the political development of mankind has gone along the forces of philosophy and of religion, revealing to the race the meaning of nature, of man, of his relation to his creator and to his fellow man. Not enough credit is attributed to these forces in the development of government, society, and civilization. It was by comprehending the natural forces of the universe that man saw he had in them a right of property and set them to be his servants. It was through a realization of the fatherhood of the Almighty that came a knowledge of the brotherhood of man, of his innate nobility, of equality, of his right to be free…

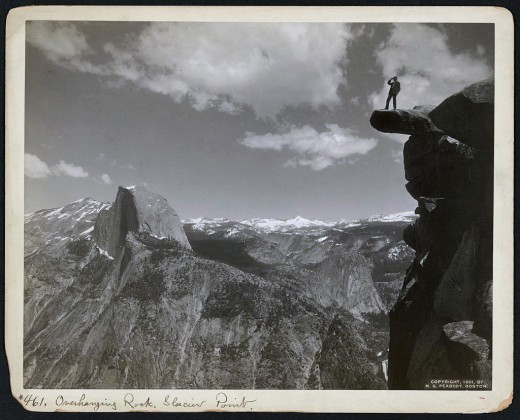

“…I have hastily sketched the development of the forms of government. That which is based on the rule of the people through a republic in principle is the ultimate. There is no beyond, there is only reaction. To that point we have arrived. There is great opportunity for improvement of administration. It is not enough that correct principles be declared in institutions, unless they result in corresponding action in practical life. By all the experience of history, by the wisdom of philosophy, by the revelations of religion, those main principles of human rights and duties set out in the Constitution of Vermont, which is so purely American, are sound and permanent, representing that course which men must follow ‘to have life and have it more abundantly.’ They represent however what ought to be, not yet what is.

“This is by no means the equivalent of saying that further effort is no longer necessary. Perfection requires not less effort but more. Great privileges mean great responsibilities. Truly freedom is not easy but hard for the people to endure.

“There is always the force of evil without and within. It is difficult to say that any great nation perished by reason of an attack by forces from without. Disintegration begins within. We have solved the problem of the distribution of power between the three departments of government. The workings of the human mind are sufficiently understood so that intellectual stagnation is no longer probable. But there are economic problems which while we can solve theoretically, practically we are as yet unable to apply satisfactorily a remedy. We are the possessors of tremendous power, both as individuals and as states. The great question of the preservation of our institutions is a moral question. Shall we use our power for self aggrandizement or for service? It has been a lack of moral fibre which has been the downfall of the peoples of the past. There came a time when they were sunk in indulgence and no longer strove for achievement. But there has been revealed to us the nobility of man, not formerly so well understood, which has taught us to appeal not to his selfishness but to his sense of duty. A nobility which reaches from the highest to the lowest and justifies our firm faith in the abiding convictions of the people.

“It is true that as yet ‘we see through a glass darkly,’ but we see enough to justify our faith in those American institutions…We see our rights shining forth with a resplendent light as the reward of fidelity to our duties. We hear our call and we go, responsive ever to that appeal of the soul:

‘Oh heart be strong!

Be valiant to do battle for the right,

Hold high truth’s stainless flag:

Walk in the light,

And bow not weakly to the rule of wrong.’ “

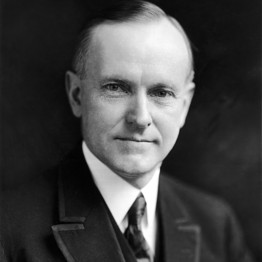

— Vice President-elect Calvin Coolidge, January 18, 1921