“The Government ought always to be alert on the side of the humanities. It ought to encourage provisions for economic justice for the defenseless. It ought to extend its relief through its national and local agencies, as may be appropriate in each case, to the suffering and the needy. It ought to be charitable. Although more than forty of our states have enacted measures in aid of motherhood, the District of Columbia is still without such a law. A carefully considered bill will be presented, which ought to have most thoughtful consideration in order that the Congress may adopt a measure which will be hereafter a model for all parts of the Union…

“In all your deliberations you should remember that the purpose of legislation is to translate principles into action. It is an effort to have our country be better by doing better. Because the thoughts and ways of people are firmly fixed and not easily changed, the field within which immediate improvement can be secured is very narrow. Legislation can provide opportunity. Whether it is taken advantage of or not depends upon the people themselves. The Government of the United States has been created by the people. It is solely responsible to them. It will be most successful if it is conducted solely for their benefit. All its efforts would be of little avail unless they brought more justice, more enlightenment, more happiness and prosperity into the home.

“This means an opportunity to observe religion, secure education, and earn a living under a reign of law and order. It is the growth and improvement of the material and spiritual life of the nation. We shall not be able to gain these ends merely by our own action. If they come at all, it will be because we have been willing to work in harmony with the abiding purpose of a Divine Providence.“

— President Calvin Coolidge, Third Annual Message, December 8, 1925

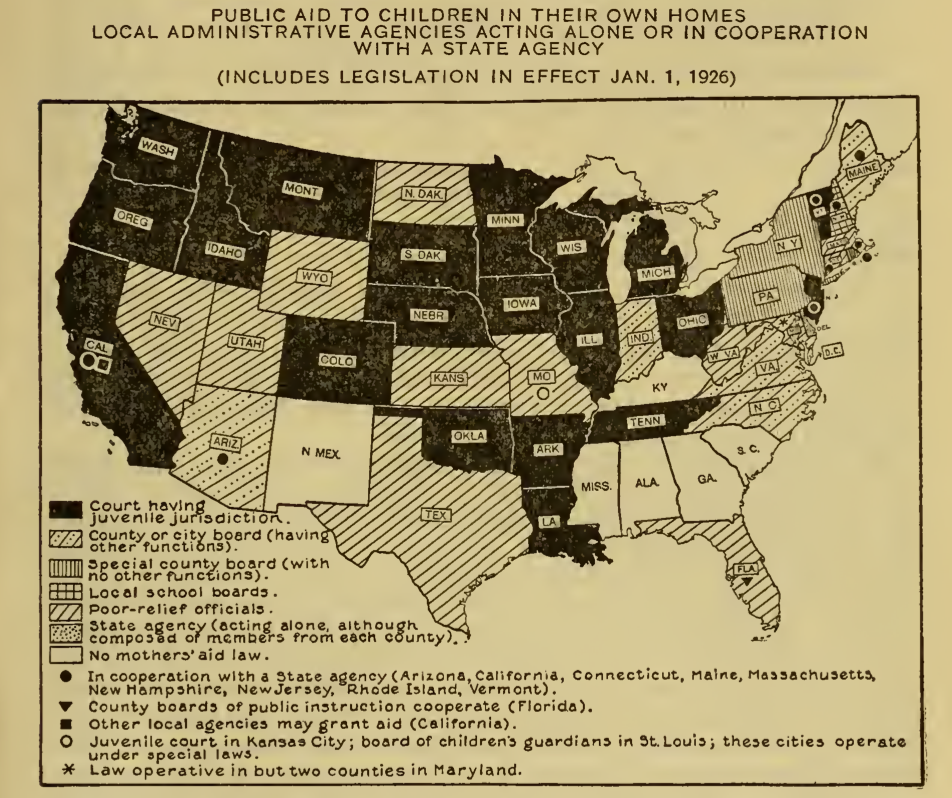

The District of Columbia, exclusively overseen by Congress under the U. S. Constitution, had not generated this movement. Instead, following the lead of legislation in 43 of the then-48 states (excluding Alabama, Georgia, Kentucky, Mississippi, New Mexico, and South Carolina, but including the handful of counties in Louisiana, Virginia, Arkansas, Tennessee, and North Carolina which administered aid for underage children), Congress had been exceedingly behind in recognizing this local initiative. Such is the way it should be, however, if efforts are truly to succeed: they start with the people themselves. At the same time, neither should the Congress act in sluggish insensibility to those they must represent. They either keep in step with the people or fall out of touch, at their own peril, with the country’s sentiments. Through the former, they understand the pulse of America and retain the confidence and trust of those they serve. Through the latter, they fail to justify their continuance as agents or officers delegated certain powers for a time by the electorate. In less than a decade most of the states had passed some form of this locally-administered support for motherhood. The states, since 1911, had clearly championed the push while the fed played catchup for which the President corrects them here. Congress would finally act on President Coolidge’s proposal in 1926 but it remained the leadership at the county and city level (courts, commissions, and municipal executives) which furnished the primary force that locally directed support not go to indigent or absentee parents but to help widowed and single mothers with the financial needs of raising dependent children into nothing less than responsible adults.