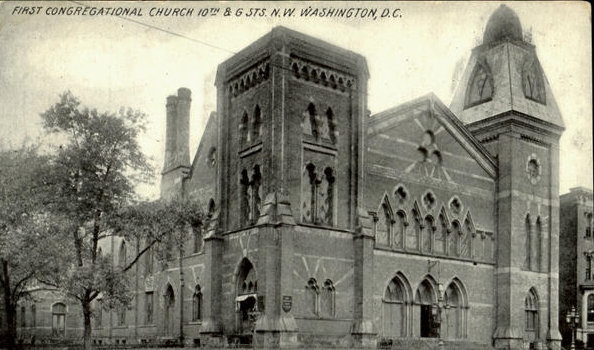

Since first arriving in Washington in 1921, the Coolidges conscientiously attended church services each Sunday at the First Congregational Church on 10th and G Streets. Established in 1865 as the first integrated congregation in the capital city, its members would not only take a significant role in the creation of Howard University — where Coolidge would give the commencement address in 1924 — but take the lead in addressing race relations years before any march on Washington. The Church, widely known for its firm opposition to racial prejudice, would be actively engaged throughout the 1920s in the Race Amity Conventions and other efforts to address social strife. It was during these years that Jason Noble Pierce served as minister to the Church.

Since first arriving in Washington in 1921, the Coolidges conscientiously attended church services each Sunday at the First Congregational Church on 10th and G Streets. Established in 1865 as the first integrated congregation in the capital city, its members would not only take a significant role in the creation of Howard University — where Coolidge would give the commencement address in 1924 — but take the lead in addressing race relations years before any march on Washington. The Church, widely known for its firm opposition to racial prejudice, would be actively engaged throughout the 1920s in the Race Amity Conventions and other efforts to address social strife. It was during these years that Jason Noble Pierce served as minister to the Church.

The Coolidges leaving church services at First Congregational, 1924

Coolidge, never one to join institutions to win political favor, could be found there each Sunday, whenever in town. He had come to respect and know Dr. Pierce back in Massachusetts. Though they had much in common, having both graduated from Amherst (Coolidge in 1895 and Pierce in 1902) and had both worked in Boston in the years preceding their almost simultaneous move to Washington, their mutual regard and friendship went deeper. For both couples, the Pierces and the Coolidges, it was a small but substantial connection with home to see friendly, familiar faces in a place so full of the different and unfamiliar. It was Jason Noble Pierce whom Coolidge wired to be waiting for him as Calvin and Grace arrived in Washington upon the sudden passing of President Harding. When Coolidge made a friend, he kept him. A consistent thoughtfulness and kind respect reached even those who never expected one of his many spontaneous gestures of generosity through the years. He loved people and, for most, it never occurred to them that their troubles weighed on his heart. Jason Noble Pierce was one such recipient, witnessing the real Coolidge.

Jason Noble Pierce, after a difficult meeting with the President on July 8, 1924, shortly after the loss of Calvin Jr. at age 16.

Dr. Pierce attempts to smile after what has proven to be an immensely tragic week for the Coolidge family and their friends.

As someone else once remarked about Coolidge and Dr. Pierce, “[I]n nothing else did he display the real greatness of his soul better than in his relationship with his pastor.” It has been said that a preacher is one of the few who sees a person as he or she is, past the outer veneer of public image and perception. Privy to the personal confidences most never see as well as the unguarded moments of an individual’s character, the preacher knows the true person. Dr. Pierce was such a minister. Looking back upon the eight years spent uniquely closer to the President than many, he would recount one of the greatest assessments of the man ever published. If anyone could see through pretense or facade, Dr. Pierce would have. He recounts Coolidge not with the blind sympathy of a fawning admirer but as he truly was, judged firsthand by one who knew him well. Jason Noble Pierce, writing in early 1933, said:

“I gladly respond to the editor’s telegram requesting that I write ‘President Coolidge as I Knew Him,’ not because I have new light to throw on that figure which is familiar to the world, but because I have long admired Mr. Coolidge, and especially since receiving the tidings of his unexpected death I have realized how many reasons I have had to love him.

“No other parishioner ever did as much for me. His thoughtfulness and courtesy were constant. For eight years it was my good fortune to be his minister, and during that entire period he was enlarging my acquaintance with me, giving me insight into important affairs, according me cultural advantages, planning for my pleasure and supporting my work. These personal traits, added to his deep interest in religion and in the work of the church, lead me to consider him the ideal parishioner.

Lucky

“The world regarded Mr. Coolidge as a shrewd, honest, plain, unassuming man of high principles, of strong convictions, successful as a practical politician. He was all that and more. He certainly was lucky. Lucky to win Grace Coolidge as his wife, and Frank Stearns as his friend. But his own personality won the former, and his ideals of public service commanded the support of the Boston merchant. He was politically lucky being the governor at the Boston police strike, and Vice President when Harding died; but these events did not make him, they made his opportunity. They revealed him. They would have been unlucky for a lesser man unequal to the demands of the occasion.

Growing

“Mr. Coolidge was a steadily growing man. I knew him first as state senator, then as lieutenant governor, then as governor, then Vice-President, then President. He seemed to me to develop and to enlarge his powers of service with each increased responsibility.

“Among all the factors contributing to this growth and development of his life I should name these three as of main influence: his religious faith, his personal loyalty, and his family love. His faith in men, in principles and in institutions naturally and logically grew out of his faith in God. His zeal in public service, devotion to his party, constancy toward his church, and fidelity to whatever cause he espoused were the fruits of personal loyalty and consecration of life. And quickening and inspiring his whole life was a most remarkable family love. He loved his father. He worshiped the memory of his mother. He intensely loved his sons, the more easily revealing that love toward the one who was younger, less robust, and whose death in Washington was a crushing blow.

His Wife

“And his admiration and love for his wife were boundless. He adored her. She fulfilled his ideals. She shared his aims. Few men and women have been so fitted for each other, supplementing each others’ gifts, working together in love and loyalty for their home, their church, and their country as Mr. and Mrs. Coolidge. This love warmed the springs of his life and gave vitality to all his personal contacts.

As Vice-President

“When he was coming to Washington as Vice-President, we tendered him the use of pew in First Church, which he accepted. He did not know that it was the pastor’s pew, chosen because no other was to be had. He liked it because it was not too far forward and he could enter and leave without being over-conspicuous. As his custom was he came promptly to church the first Sunday he was in Washington: and during the entire period of his Vice-Presidency, over two years, if he was in the city he was in his own pew. I think I could count his absences on my thumbs.

“How like him it was, at the time the Unknown Soldier was about to be buried in Arlington and tickets to the amphitheatre were priceless and practically unobtainable to hand to an usher at the Sunday morning service an envelope addressed to myself. I opened it in the pulpit, thinking that it was a pulpit announcement, and found two reserved seat admissions to the Arlington exercises.

The First Dinner

“How typical of him it was that when the Coolidges gave the Vice-Presidential dinner to President and Mrs. Harding they surprised their pastor and wife with invitations. Because guests are limited in number and invitations are greatly coveted and bestowed for social and political consideration, their kindness was emphasized.

“After a gathering of Amherst alumni at the Cosmos Club the Vice-President was escorted to his car by the president of the National Geographic Society, Gilbert Grosvenor. When Dr. Grosvenor returned to the room he drew me aside and said, ‘The Vice-President certainly is a booster for your church. He asked me why I did not attend there, and pressed the invitation so strongly that I had to state that I attended elsewhere and could hardly change, as my wife came from old Scotch Presbyterian stock. But he was so in earnest that I was surprised and deeply touched.’ So was I. I narrate these incidents as giving a glimpse of the man before he became President. He continued always to possess the same qualities.

“Two things attended his elevation to the chief magistracy of our nation–a deepening of his sense of dependence upon God and his acceptance of those ceremonial forms through which our democratic people seek to honor their President.

From His Heart

“I do not know all that happened on that historic night when he took the oath of office in the farmhouse in Vermont, but I am certain that from his heart he prayed. Surely he sought wisdom and support from God. An evidence of his desire for spiritual support was his telegram to his pastor to meet him on his arrival in Washington. But the clearest and most touching manifestation of his sense of need of God if he was to be adequate to his high office, was his partaking of the holy sacrament on that first August Sunday [Coolidge, reflecting later on this occasion and his formal affiliation with First Congregational Church, would underscore both his personal relationship with God and his desire to publicly serve, “Had I been approached in the usual way to join the church after I became President, I should have feared that such action might appear to be a pose, and should have hesitated to accept…But if I had not voluntarily gone to church and partaken of communion, this blessing would not have come to me. Fate bestows its rewards on those who put themselves in the proper attitude to receive them,” Autobiography pp.180-1]. Always before then, Mr. Coolidge had remained through the Communion service, reverent and sympathetic, but not partaking of the bread and wine. But then and thereafter he always partook. He needed God. I know he found Him.

Moved Forward

“Being an unostentatious, quiet, home-loving man, he had to learn to accept the forms and ceremonies surrounding the President philosophically. He was moved forward in church to a conspicuous pew so far forward that the secret service men from all parts of the church could watch everybody around him. Mostly this is to guard the President from cranks and ill-advised people who have some personal cause to plead and fail to reach the President through proper channels.

“The congregations stood when he arrived and departed and the minister escorted him from his pew. I appreciated the opportunities that little recessional afforded for a few words with him, especially if I had a cause to commend or some comment to make.

One Mile Around

“One snowy Sunday, thinking of the broad walk around the White House grounds, I said, ‘If there was a custom that every man had to shovel his own walk, some people who envy you, Mr. President, would hesitate to have your job.’ His matter-of-fact reply was, ‘It’s just one mile around the grounds. I paced it off last week.’

All Souls Church in Washington, D.C., at 16th and Harvard Streets.

“On another Sunday he said, ‘I attended the dedication of All Souls Church last week [Chief Justice Taft’s congregation, dedicated in 1924, where another Dr. Pierce, JNP’s namesake, worked, the Reverend Ulysses Grant Baker Pierce], and heard your namesake preach.’ I replied that I was delighted he had gone and I knew he had heard a fine sermon. As I turned to speak to Mrs. Coolidge the President turned back, nudged my arm and said, ‘It was two sermons.’

Talk and Action

“Those were great days for me and mine. Meeting a former ‘President’s pastor’ on the street one day, I was subjected to interrogation. ‘Have the Coolidges ever invited you and your wife to dine at the White House?’ ‘Yes.’ ‘With just the family or at some formal dinner?’ ‘Both.’ ‘Ever had you on the Mayflower?’ ‘Yes.’ ‘You don’t say. Do they invite you to the musicales by famous artists in the East Room?’ ‘Yes.’ ‘Well, Pierce, all I can say is that you are lucky and I’m glad for you. President X (mentioning his former Presidential parishioner) often said to me that he was going to have us, but he only talked about it and never did anything.’ Yes, truly that was the difference. President Coolidge acted without talking about it. He would not approve my talking about it, either, and I do so only to reveal him. I doubt that any former President was so considerate of his pastor. At the time our National Congregational Council met for over a week in Washington, he invited all of his former pastors to be his guests at the White House for the entire period, and stipulated that among several others he and Mrs. Coolidge so entertained there should be some home missionaries and others of limited privileges.

“Never could he have borne the strain of office if he had not had a lively sense of humor and unusual power of relaxing. He could be the most dignified of Presidents in public, and again he could unbend as a child. His humor involved myself on one occasion. He was to attend a football game between two teams representing the Army and Navy. At the start he was to throw out the football. Sitting with the Navy the first half and with the Army the second half, he was to be formally transferred during the intermission. Somebody died whose funeral he had to attend, and he appointed me to act in his place and receive his honors at the game. During the intermission the Secretary of the Navy and a string of Admirals gravely escorted a preacher to the middle of the field and solemnly turned him over to the War Department and a squad of Generals. And somewhere at a funeral service I think the President, at least for a moment, had a gleam in his eye and a curve on his lip.”

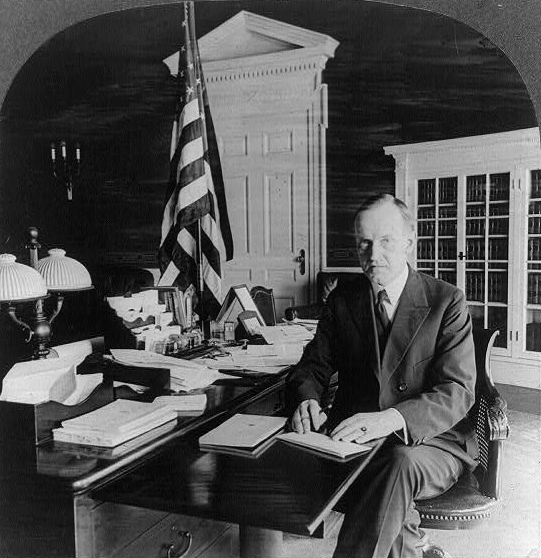

President and Mrs. Coolidge, 1924