When the enormous delegation from Hammond, Indiana, stepped off the train and went to make their request at the White House on March 11, 1927, little would anyone realize the significance their visit would have on the future or the power of the statement it represented. They had not come to request money, propose an appropriation or even lobby for Federal patronage. They had come with something far more altruistic and responsible in mind. Instead of what they could get from Washington, they were inspired by what they could give, how they could promote, not themselves, but the efficacy of solvent local governments, civic-minded neighborhoods and proactive citizenship. Ever determined to pay their own way, they arrived not with the expectation of political or monetary reimbursement but to approach the President as their equal in citizenship. Quietly honoring the sovereign balance between states, the people and their national government, the Hammond delegation invited President Coolidge, as their guest, to dedicate a 225-acre park they had already acquired, paid for and provisioned so that posterity, memorializing the veterans of World War I, would be able to enjoy both the beauty of the outdoors and the rejuvenation afforded by its opportunities for wholesome recreation.

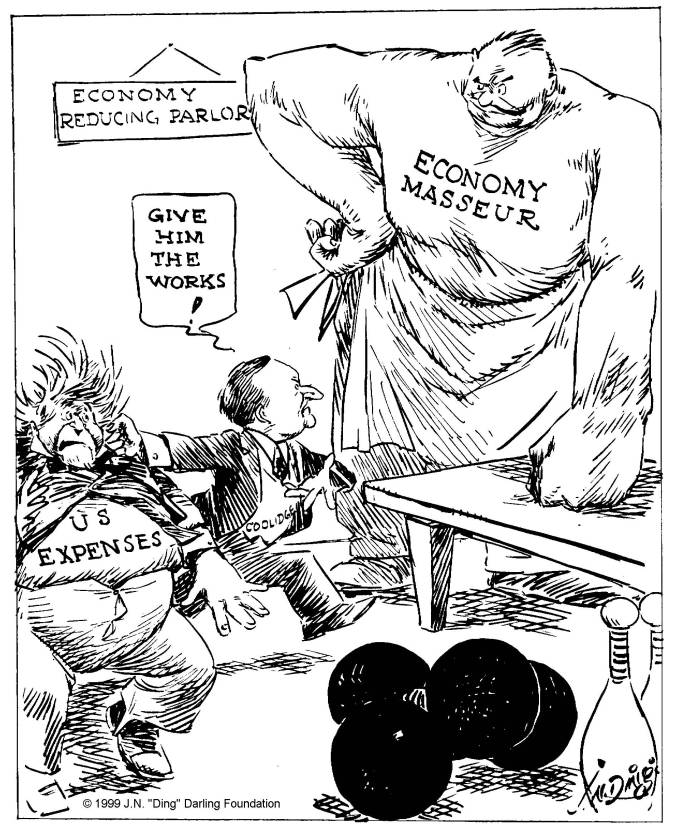

Of course, the President’s travel would cost just as would the attendant expenses of his stay. However, they knew in Mr. Coolidge there was someone who could masterfully save public money, finding ways not only in avoiding debts but amassing surpluses on even the cheapest of trips. A negotiation ensued. Perhaps he could give the speech that morning and “save…the trouble of going out there,” Coolidge offered. Well, that would curtail their time to speak now on the merits of their park, their neighborhoods and their people. They were here to underscore the strength of local civic participation after all. Ever respectful of that sovereign principle, Cal deferred and as the plan for his visit to their town took shape in the coming months, he would endorse their example in word as well as deed.

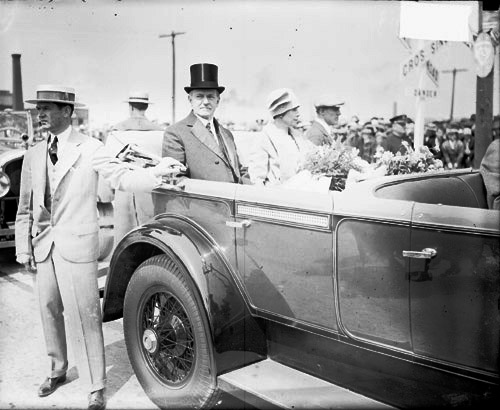

By stopping in Hammond only two hours en route to his famous stay in the Black Hills that summer, leaving immediately after the simple ceremony, Coolidge avoided the costs of accommodations, food, and the endless parade of elaborate outlay expected to accompany a Presidential visit. He detested ostentatious displays, especially at the hands of government officeholders, in part because of his own self-effacing nature but also because it always exacted a tax for which people had to work longer hours for fewer wages, seeing less a reward for themselves and more for those who have not earned it. Even on the road, Coolidge would practice economy. He would stay in unassuming places, attend rural church services rather than the grand churches of the nearest city and exercise the powers of his office to serve, not be served.

The story is told of the strenuous efforts to provide a pristine washroom for the President during one of his stops on the road. Newly supplied with soap and clean, white towels, every corner of the room was ready for his arrival. Moments before being shown these facilities, however, a hot and dusty aide hurried to the room, drying his hands on one of those towels. Claude Fuess recounts what happened next, “When the President was escorted to the washroom, his companion noticed that one of the towels was streaked with dirt, and proffered him the remaining one, but Coolidge waved him aside, saying, ‘Why soil it? There’s one that’s been used. That’s clean enough.’ ” As Fuess aptly summarizes, the account would “hardly be worth relating” if not for the light that it sheds on Coolidge’s consistent sense of humility and economy (Calvin Coolidge: The Man from Vermont, pp.487-8).

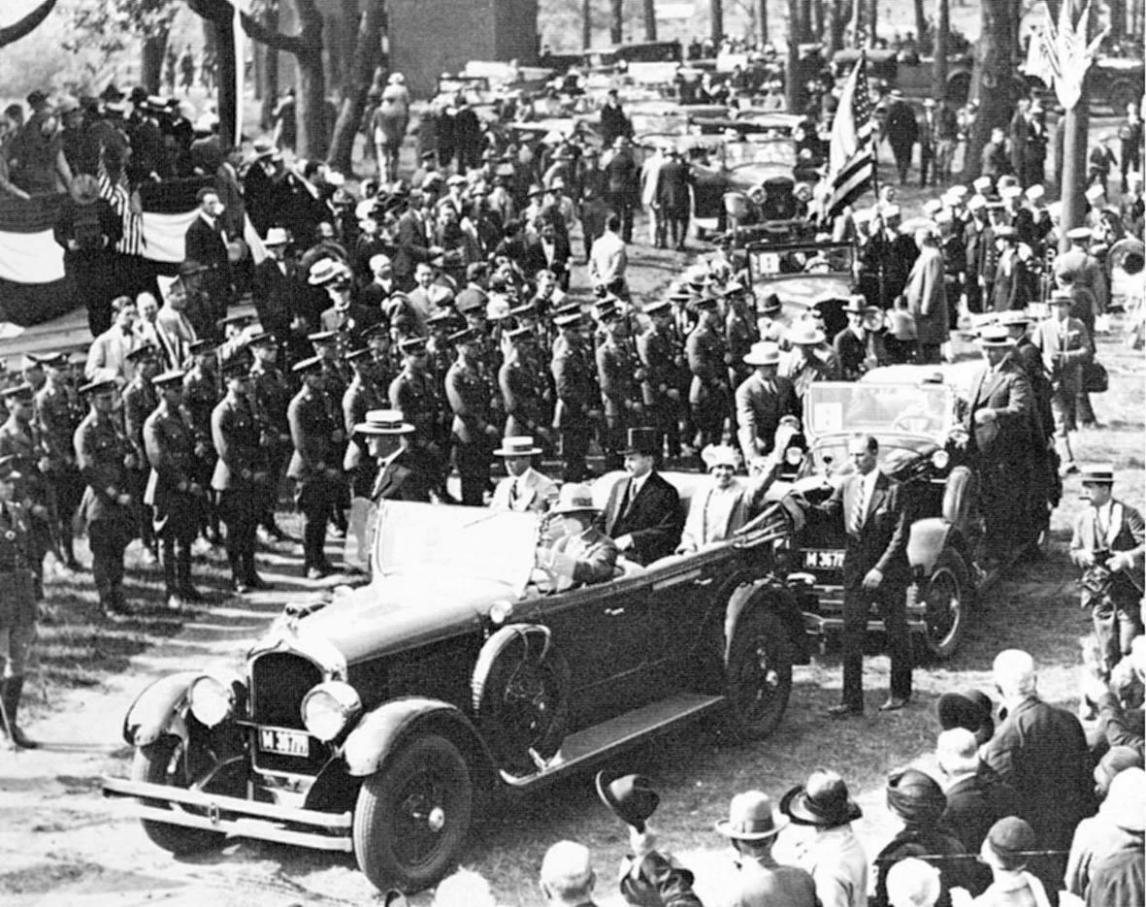

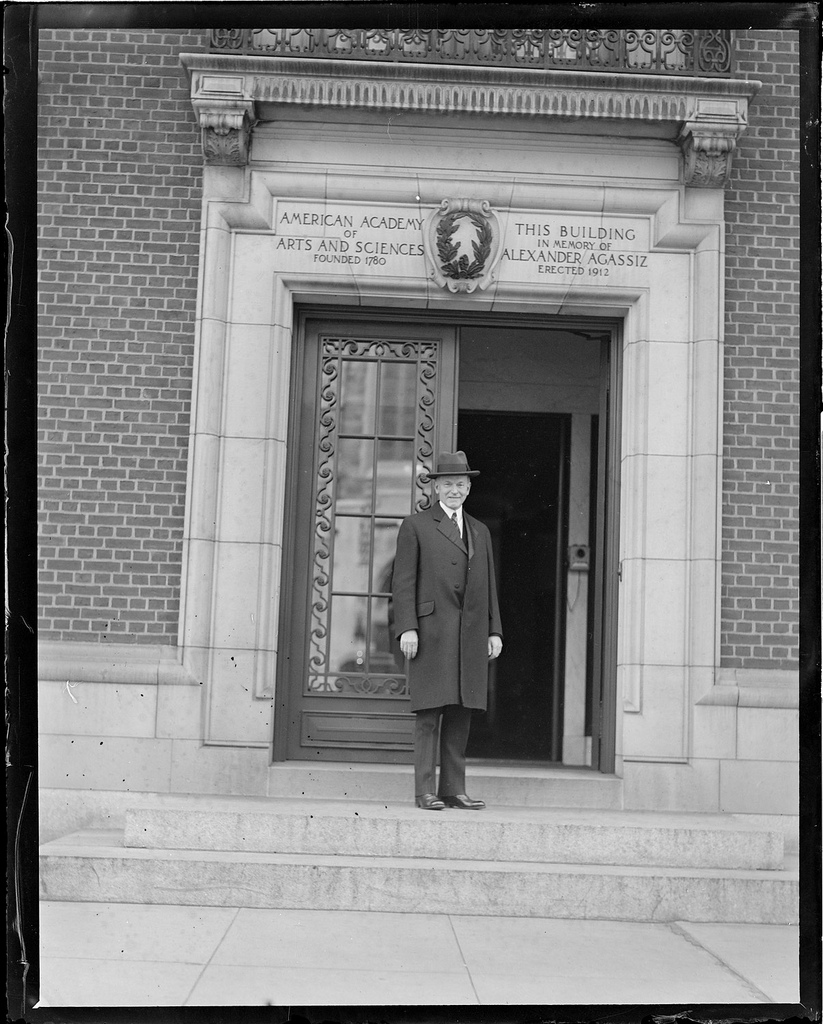

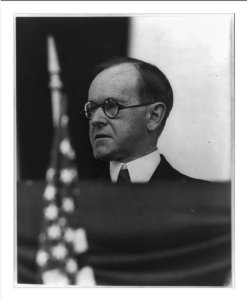

The President faces his audience – 150,000 strong – at the dedication of Wicker Memorial Park, Hammond, Indiana

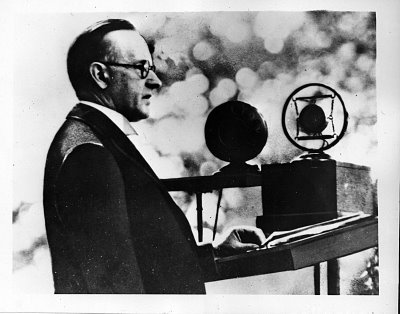

Looking out across the crowds past the baseball field, walking trails, tennis courts and 18-hole golf course, Coolidge saw something more as he began,

“Fellow Citizens:

“This section represents a phase of life which is typically American. A few short years ago it was an uninhabited area of sand and plain. To-day it is a great industrial metropolis. The people of this region have been creating one of the most fascinating epics. The fame of it, reaching to almost every quarter of the globe, has drawn hither the energetic pioneer spirits of many different races all eager to contribute their share and to receive in return the abundant rewards which advancing enterprise can give…Here are communities inspired with a strong civic spirit moving majestically forward, serving themselves and their fellow men. Here is life and light and liberty. Here is a common purpose – working, organizing, thinking, building for eternity.” This vibrant collaboration was not instituted by government mandate, it flowered under the care of the people themselves. Moreover, it was a structure built by all races, a legacy on which everyone had left an impression and contributed a part. Such is the nature of liberty. Coolidge could easily have said the converse is equally as possible: Without a constantly replenished civic spirit, a community soon experiences death, darkness and slavery.

As Coolidge kept his commitment to speak at the dedication of Wicker Memorial Park, the visit of that large delegation stuck with him. He likely saw many of those familiar faces among the 150,000 who were there that day. He was not there to honor himself, he was there to commemorate the sacrifice of those who, not unlike the engaged citizens of Hammond, had done more than simply talk about what needs to be done, they got busy and did what needed doing. The veterans of the World War took up the full burden of American citizenship. It is only fitting that they were in turn honored by those ready to partake in that higher kind of devotion. “Not the visionary variety,” Coolidge observes, “which talks of love of country but makes no sacrifices for it, but the higher, sterner kind, which does and dares, defending assaults upon its firesides and intrusion upon its liberty with a musket in its hands.” The men and women of Hammond were not lawless anarchists or violent deviants, but “orderly, peaceable people, neither arrogant nor quarrelsome, seeking only those advantages which come from the well-earned rewards of enterprise and industry.” As a result, the people of Hammond, like Americans all across the country, were simply demonstrating what it means to responsibly exercise American citizenship.

As he stepped to the podium, Coolidge’s mind would turn again to the astounding achievements of this region of Indiana, he would reflect on the rapid but substantial rise from wilderness to thriving neighborhoods, towns and metropolises. These were not developments over which to mourn, they exemplified the strength and progress of men and women engaged in their own communities, free to direct their own destinies and make their own decisions. They embodied self-government at its finest. With local obligations being met so proficiently, it made the intervention of national authority unnecessary, redundant and destructive. The better local institutions work, as the citizens of Hammond proved, the less room there remains for central government to justify its presence. This exemplary success of civic participation was not from some coincidental combination of factors in history, as if it were all by accident, it was directly a result of the daring spirit of Americans themselves. It came from the character they possessed. As the President would remark on that occasion, “It is inconceivable that it could take place in any land but America.” The very ground on which they stood was testament to that truth. It had once been a dry, sandy plain. Now it was a garden appealing not only to the mind but to the spirit of man. It was conceived and carried out not by the votes of politicians but through the effort and perseverance of citizens who recognized they had an obligation to give, not merely to take. Men like George Hammond, whose packing plant helped establish the town; or the 16 men of North Township who joined together to bequeath this large property to posterity for its practical usage in bettering people.

As he stepped to the podium, Coolidge’s mind would turn again to the astounding achievements of this region of Indiana, he would reflect on the rapid but substantial rise from wilderness to thriving neighborhoods, towns and metropolises. These were not developments over which to mourn, they exemplified the strength and progress of men and women engaged in their own communities, free to direct their own destinies and make their own decisions. They embodied self-government at its finest. With local obligations being met so proficiently, it made the intervention of national authority unnecessary, redundant and destructive. The better local institutions work, as the citizens of Hammond proved, the less room there remains for central government to justify its presence. This exemplary success of civic participation was not from some coincidental combination of factors in history, as if it were all by accident, it was directly a result of the daring spirit of Americans themselves. It came from the character they possessed. As the President would remark on that occasion, “It is inconceivable that it could take place in any land but America.” The very ground on which they stood was testament to that truth. It had once been a dry, sandy plain. Now it was a garden appealing not only to the mind but to the spirit of man. It was conceived and carried out not by the votes of politicians but through the effort and perseverance of citizens who recognized they had an obligation to give, not merely to take. Men like George Hammond, whose packing plant helped establish the town; or the 16 men of North Township who joined together to bequeath this large property to posterity for its practical usage in bettering people.

“Such a people always respond when there is need for military service.” The service Hammond was rendering was hardly the first time that area had known sacrifice. Every war down to the latest World War had seen Hammond give of its own to something greater than accolades or recognition. It had helped decide the “chief issue” of the Great War: “whether an autocratic form or a republican form of government was to be predominant among the great nations of the earth. It was fought to a considerable extent to decide whether the people were to rule, or whether they were to be ruled; whether self-government or autocracy should prevail. Victory finally rested on the side of the people…This park is a real memorial to World War service because it distinctly recognizes the sovereignty and materially enlarges the dominion of the people. It is a true emblem of our Republic.”

The President elaborated on this concept by looking back through history. Ancient gardens and Old World parks “had little to do with the public. Parks were private affairs for the benefit of royalty and the nobility.” Recent past had seen an outpouring of interest and investment “in our country…for these important functions.” But here, in stark difference from antiquity, these places of recreation are as important as where people work and live. They are just as essential as homes and workplaces in rearing a people “who are fit to rule.” It was uniquely and “triumphantly American” that places like Wicker Park take on such importance in the community. Since, Coolidge explains, “[i]in this country the sciences, the arts, the humanities, are not reserved for a supposed aristocracy, but for the whole of the people. Here we do not extend privilege to a few, we extend privilege to everybody. That which was only provided for kings and nobles in former days, bestow freely on the people at large. The destiny of America is to give the people still more royal powers, to strengthen their hand for a more effective grasp upon the scepter.”

Even with all the progress America has brought, “we are still a great distance from what we would like to be.” Education, religious devotion and economic opportunities need further improvement. Recognizing that we are far from perfection, these all deserve the best we can render to close that distance and “work toward…elimination” of our shortcomings in regard to God and man. “But we should not be discouraged because we are surrounded by human limitations and handicapped by human weakness. We are also possessors of human strength, intelligence, courage, fidelity, character – these, also, are our heritage and our mark of the Divine image.” We neglect that truth to our peril. “The conclusion that our institutions are sound, that our social system is correct, has been demonstrated beyond question by our experience. It is necessary that this should be known and properly appreciated.” The President then predicted what would happen should this fail to be done. “Unless it continues to be the public conviction, we are likely to fall a more easy prey to the advocates of false economic, political, and social doctrines. It is always very easy to promise everything. It is sometimes difficult to deliver anything. In our political and economic life there will always be those who are lavish with unwanted criticism and well supplied with false hopes. It is always well to remember that American institutions have stood the test of experience. They do not profess to promise everything, but to communities and to individuals who have been content to live by them they have never failed in their satisfactions and rewards. Here industry can find employment, thrift can amass a competency, and square dealing is assured of justice.”

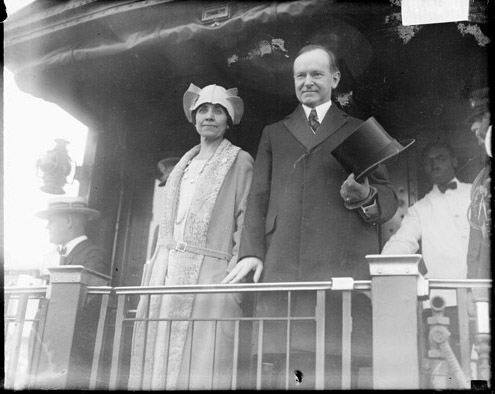

As Coolidge neared the end of his dedicatory message, he returned to the importance of what was not merely being said over the microphone, but what was being lived in the deeds of communities like Hammond and the people of North Township but in places all across America. It had to continue. Civic participation — the substance of an active, engaged citizenship — had to be nurtured and continually developed or else stagnation and decay would result. Crucial to the strength of that civic spirit are the unseen realities: the ideals of this country. “Amid all her prosperity, America has not forgotten her ideals,” the President testified. He saw their vigor and life at every stop along the tracks to South Dakota that summer. He saw them in the accomplishments of young men like Charles Lindbergh. He also saw them in the simple acts of kindness shown by the children the Coolidges met on that trip. Calvin would joyfully take up one of them, a little girl of six years, in his arms in appreciation for the bouquet she had for Mrs. Coolidge. It was Cal, welcoming all the children who had come with flags, flowers and tokens of their patriotism, dismissed the Secret Service’s well-intentioned efforts to prevent them. The love those children had for America was not something to shame and disparage but to keep kindled and encouraged. It was, after all, the seed of a greater and greater civic involvement that would preserve communities’ soundness and self-sufficiency by keeping governance nearest to those it concerned. “It is but a passing glance that we bestow upon wealth and place,” Cal would say as he closed his message at Wicker Park, “compared with that which we pour out upon courage, patriotism, holiness, and character. We dedicate no monuments to merely financial and economic success, while our country is filled with memorials to those who have done some service for their fellow men. This park stands as a fitting example of these principles. It is a memorial to those who defended their country in its time of peril. Through the benefits that it will bestow upon this community, it is an example of practical idealism.”

As Coolidge surveyed the hundreds of thousands of Americans who filled the park that day, he saw in our future not a sapping despair or delusion of cynicism but one bright with better things in store, a future resplendent with the potential of a free and actively engaged citizenry. That future, however, was conditional. If our country was to lead the way toward realizing “a world fit for the abode of heroes,” as Coolidge sincerely wanted, “it can only be through the industry, the devotion, and the character of the people themselves. The Government can help to provide opportunity, but the people must take advantage of it. As the inhabitants of the North Township repair to this park in the years to come, as they are reinvigorated in body and mind by its use, as they are moved by the memory of the heroic deeds of those to whom it is dedicated, may they become the partakers and promoters of a more noble, more exalted, more inspired American life.” He knew Americans, taking responsibility themselves rather than waiting for government to act, were more than up to this challenge. It remains for us to prove we are now.