President Coolidge stood before those gathered at the National Conference on Outdoor Recreation, May 22, 1924, to address the importance of developing not only sound minds but also sound bodies. What made this possible, however, was not thanks to Washington’s involvement. It would never succeed to mandate or coerce fitness programs. It was going to come from taking advantage of the opportunities America’s liberty affords. He would observe the lifestyles of people had changed from those early days of settlement, when most worked outdoors and acquired the exercise of “active outdoor life in the open country.” Such was not so widespread anymore, Coolidge noted. However, “All of this makes it more necessary than ever that we should stimulate every possible interest in out of door health-giving recreation.” The President would emphatically remind his audience that this was not a responsibility of the Federal Government. “Necessarily they are largely local and individual, and to be helpful they must always be spontaneous.” There was no place for Washington telling people what to eat or how to exercise. To do so would defy freedom and undermine the very purpose of voluntary activity.

The conference should not expect him or any one else in the District to furnish the solutions. What the conference could do was bring private individuals together and coordinate their resources with ingenuity, exercising decisions at the local level for ways to restore the “natural balance of life” with both its physical and mental cultivation. For Coolidge, outdoor activities in all its forms — exercise, gardening, hunting, fishing and sports among so many others — afforded Americans the advantage of cherishing the wholesome in life. It knew no ethnic or racial bounds, it was a means to developing character, “a universal appeal.” Coolidge had seen men and women, of all backgrounds, work side by side during the War and that needed to continue in peace. Competitive sports — foremost baseball — afforded one such way to fully share in the identity of what America meant. While the rigors of training did not open participation in certain sports to the general public, such games “have no superior” when it came to “creating an interest which extends to every age and every class, for giving an opportunity for a few hours in the open air which will provide a change of scene, a new trend of thought, and the arousing of new enthusiasm for the great multitude of our people…”

If activities did not “represent an opportunity for a real betterment of the life of the people,” they were not worthy of America. They must “minister directly to the welfare of all our inhabitants.” The entertainment of ancient Greece and Rome, while they may have started on this ideal plane were, in the end, corrosive to the good and virtue of all people. Such could not be allowed a foothold in America’s pursuit of recreation. “It is altogether necessary that we keep our own amusements and recreations within that field which will be prophetic, not of destruction, but of development. it is characteristic of almost the entire American life that it has a most worthy regard for clean and manly sports. It has little appetite for that which is unwholesome or brutal.” Such ideals are what the moral experiment of America was all about.

Athletics and activity were a crucial resource to allocate and encourage, but it cannot be planned or enforced from a central government. It was up to the parents, civic-minded organizations, and volunteers in each neighborhood to foster a healthy balance of work and play. The supposed “High Priest of Big Business” (according to ignorant historians), President Coolidge, explained that balance as he continued speaking, “Our youth need instruction in how to play as much as they do in how to work. There are those who are engaged in our industries who need an opportunity for outdoor life and recreation no less than they need opportunity of employment. Side by side with the industrial plant should be the gymnasium and the athletic field. Along with the learning of a trade by which a livelihood is to be earned should go the learning of how to participate in the activities of recreation, by which life is made not only more enjoyable, but more rounded out and complete.”

As recreation, including sports from hunting to football, become less about the balance of good character in all people, and more about eradication of life’s risks, the good is being regulated away. When government is allowed to intervene in the name of public safety, to foster an environment of central management, ministering only to material gain, it deprives society of the intangible value of voluntary activities and outdoor exercise when and how individuals choose. Government, with all its good intentions, always fails to supply the needs of the soul and in the end, a people is left devoid of balance, empty, divided and dependent.

It was once understood by that man from Vermont that exercise and recreation “should be the means to acquainting all of us with the wonders and delights of this world in which we live, and of this country of which we are the joint inheritors. Through them we may teach our children true sportsmanship, right living, the love of being square, the sincere purpose to make our lives genuinely useful and helpful to our fellows…Our country is a land of cultured men and women. It is a land of agriculture, of industries, of schools, and of places of religious worship. It is a land of varied climes and scenery, of mountain and plain, of lake and river. It is the American heritage. We must make it a land of vision, a land of work, of sincere striving for the good, but we must add to all these, in order to round out the full stature of the people, an ample effort to make it a land of wholesome enjoyment and perennial gladness.”

President Coolidge throwing the opening pitch in this 6-5 win by the Senators over the Yankees, April 22, 1924. Coolidge’s record stands at 3-1 for wins following opening pitches for the Senators. His only loss came from Boston beating Washington in 1928. As for the World Series, Coolidge threw first pitch for game one (1924), was present for games six and seven, and pitched again for game three in 1925. 1924 was the one and only championship for the National Capital to date.

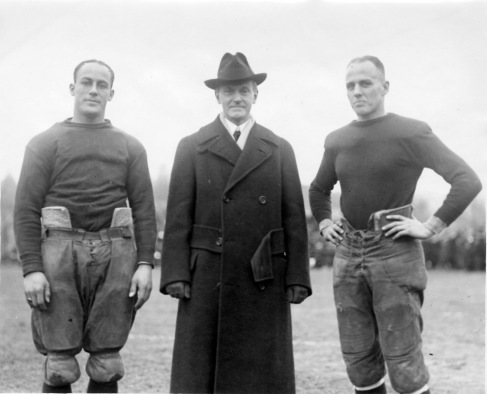

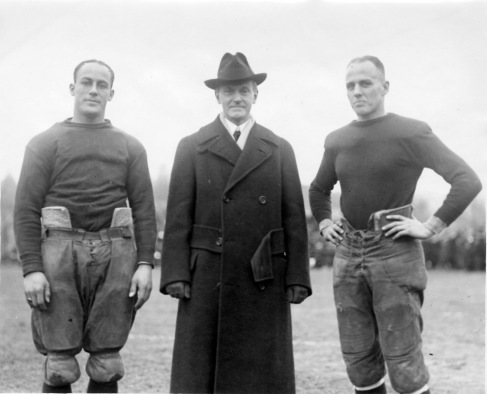

Vice President-elect Coolidge meeting the team captains in 1920’s Amherst versus Williams game.

President Coolidge successfully hunting fowl in Georgia during his brief stay there in 1928.

Coolidge, in the summer of that same year, fishing on the Brule River in Wisconsin with the faithful Rob Roy and their guide John LaRock. Notice Coolidge’s aptly christened canoe.

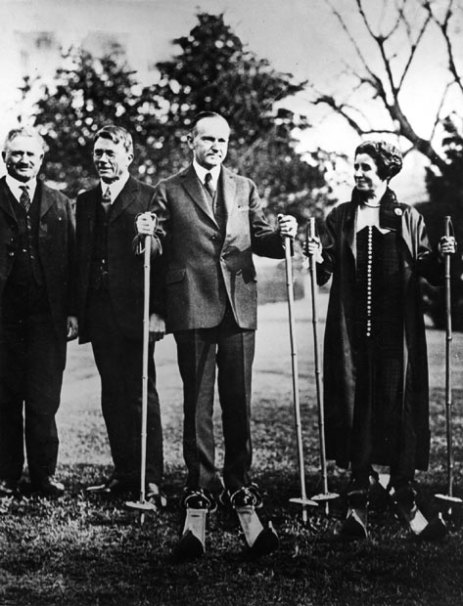

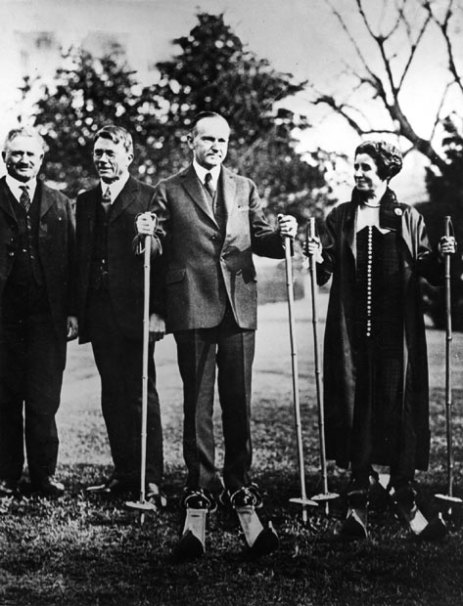

Ready to hit the slopes with the Coolidges…now for the snow…