It was on this day eighty-six years ago that the President and First Lady came to Andover, Massachusetts, to join in the celebrations of one of the oldest chartered secondary schools in America, marking its one hundred and fiftieth anniversary, May 19, 1928. Phillips Andover, established in 1778, is now two hundred and thirty-six years of age, virtually born with the country. While it has built a long and distinguished reputation, with alumni including two presidents, numerous judges, educators, scholars, statesmen, entrepreneurs, architects, diplomats, military heroes, economists, authors and actors, from Oliver Wendell Holmes Sr. (1825) and Frederick Law Olmstead (1838) to Bill Belichick (1971) and John F. Kennedy Jr. (1979). It is necessary, however, to do more than take stock of where we now are but look back at the foundations of this institution for a renewed sense of purpose and revitalized direction ahead. Coolidge calls us to reflect on the man whose devoted character established this academy and who still summons all Americans to live worthy of its ideals.

President Coolidge, addressing the crowds in Andover that day, said,

“My Fellow Citizens:

“It is more than the passage of time that brings us here to observe and celebrate this anniversary of Phillips Academy. One hundred and fifty years is a very respectable period of modern history. The number of chartered institutions which can claim an existence of that length is not large. The significance of this occasion, however, lies not in the number of days but in the importance of purpose and the magnitude of accomplishment. This institution had its beginnings in a very interesting era. The morning mist at Lexington and Concord had scarcely been dissipated. The Declaration of Independence was still a novelty. Liberty and independence were in the making. A new nation was coming into existence. Men were turning toward the dawn, intent upon establishing institutions stamped with their own individuality…

“…The new academy was to represent the spirit of the time. It stood upon foundations that were deeply religious. Its first and principal object was declared to be ‘the promotion of true piety and virtue. It provided instruction in the classics, the sciences, and the arts’…But this academy was conceived to have a broader purpose than to serve any profession or class, and it was therefore dedicated to teaching students ‘the great end and real business of living.’ It was to be ‘ever equally open to youth of requisite qualifications from every quarter.’ It was to be a national school of breadth and vision, of freedom and of equality, dedicated without reserve to the service of God and man.

“It has always been recognized that this school owes very much of the atmosphere which has always surrounded it to the character of Samuel Phillips, Jr. It was the inspiration of a young man seeking to minister to young men. When he became the object of a little envy by some of his fellow students at college, we find him writing to his father: ‘Let me be interested in the Lord and no matter who is against me.’ Such a statement from the pen of Judge Phillips was neither form nor cant, but the expression of his abiding faith in the great realities. Yet he was intensely interested in the people about him and in current affairs…He was not a recluse, but rather a leader and an organizer, even in his undergraduate days, with the natural social qualities of youth. Samuel Phillips has applied himself to his work, he had followed the truth, he had brought his faculties under discipline. His mastery over himself gave him a mastery over his associates, and imparted not only to his work, but to his pleasures, a dignity and a character…For his own part he committed himself whole-heartedly to the Revolution. We find him during the Battle of Bunker Hill removing the Harvard library to a place of safety. He was one of a number of citizens to confer with General Washington at Cambridge, and was later producing gunpowder for the Army. But he was not so much interested in warfare as he was in truth and liberty. He does not rank as a soldier, but as a statesman.

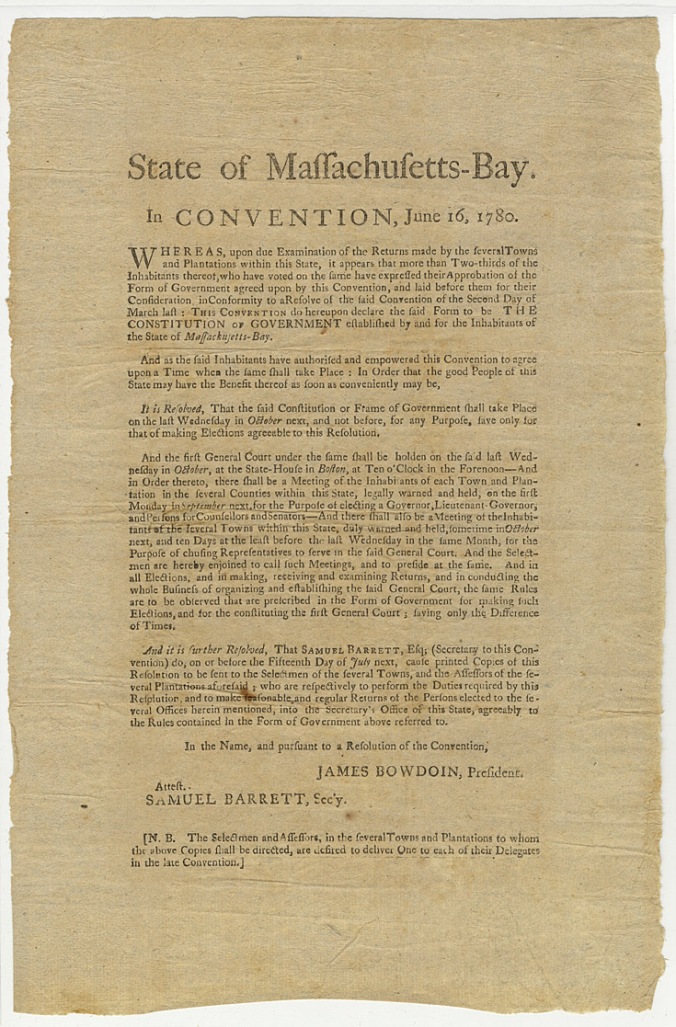

“While plans were being perfected for this academy, Judge Phillips was a member of the constitutional convention of the Commonwealth, where he served on a special committee to draft a declaration of rights and frame of government…In this work he was associated with such men as John Adams and James Bowdoin…[T]he preamble and declaration of rights…then adopted…contains more political wisdom, sound common sense, and wise statesmanship than I have ever seen anywhere else within a like compass. If it could be faithfully expounded to the youth of our country it would do much to rescue them from unsound social and political doctrines…

“In the frame of government there is a noble expression of the aims of education and the arts and a wise provision for their promotion and protection by the public authorities. These were the beliefs and opinions that Judge Phillips and his associates held. For their perpetuation and preservation this school was founded.

“The character of the founder and the attendant circumstances gave it a very broad outlook. Everything provincial was disregarded. It has always been and is now decidedly national in its scope…While careful provision was made to increase the intellectual power of the students, even greater emphasis was placed on increasing their moral power. The attention of the master was especially directed to the fact that ‘knowledge without goodness is dangerous,’ and he was charged constantly to instruct the students in the precepts of the Christian religion. Our doctrine of equality and liberty, of humanity and charity, comes from our belief in the brotherhood of man through the fatherhood of God. The whole foundation of enlightened civilization, in government, in society, and in business, rests on religion. Unless our people are thoroughly instructed in its great truths they are not fitted either to understand neglectful of their responsibilities in this direction is to turn their graduates loose with simply an increased capacity to prey upon each other. Such a dereliction of duty would put in jeopardy the whole fabric of society. For our chartered institutions of learning to turn back to the material and neglect the spiritual would be treason, not only to the cause for which they were founded but to man and to God.

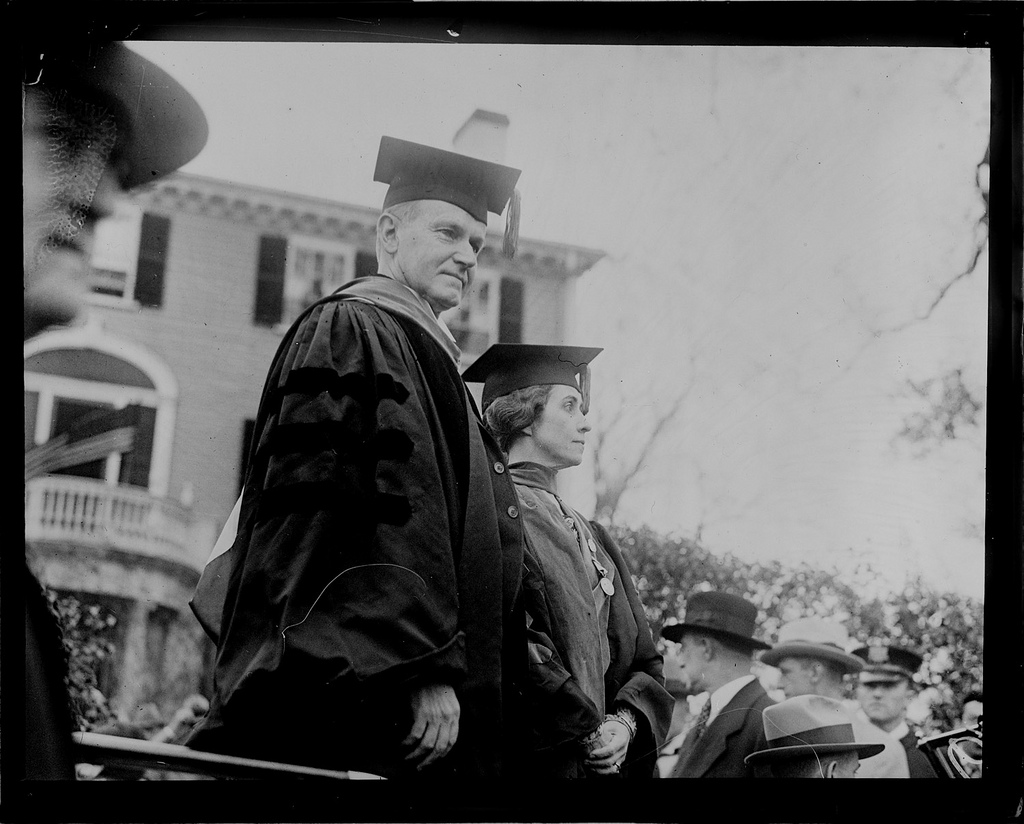

The Coolidges, both college graduates, in academic cap and gown during their visit to the 150th Anniversary of Phillips Academy. To their right stands the Headmaster, Alfred Stearns; to their left, Alfred L. Ripley (believe it or not).

“One of the results of these beliefs led this school to come out squarely for equality. It provided an opportunity which was to be open to all. Our country has rightly put a very large emphasis on this principle…Yet there has been great difficulty in bringing the Government within its operation. At its outset there was a tendency to establish a ruling class consisting of wealth and social position. When that was overturned the other extreme prevailed, which was followed by a fluctuating back and forth between these two. Neither of them is in harmony with our theory of equality. Our country and its Government belongs to all the people. It ought not to be under the domination of any one element or any one section. For it to fall under the entire control of the people of wealth or people of poverty, of people who are employers or people who are wage earners, would be contrary to our declared principles. They should all be partakers in the responsibilities and benefits, and all be represented in the administration of our Government. Those who are charged with the conduct of our affairs should be equally solicitous for the welfare of all localities and all classes. There should be no outlaws and no favorites, but all should be beneficiaries of the common good through the discharge of common duties.

“It was the thought of Judge Phillips to give to our youth the benefit of careful training during their early years. He knew that unless correct habits of thought are formed at the very outset of life they are not formed at all. Two great tests in mental discipline are accuracy and honesty. It is far better to master a few subjects thoroughly than to have a mass of generalizations about many subjects. The world will have little use for those who are right only a part of the time. Whatever may be the standards of the classroom, practical life will require something more than 60 per cent or 70 per cent for a passing mark. The standards of the world are not like those met by the faculty, but more closely resemble those set by the student body themselves. They are not at all content with a member of the musical organizations who can strike only 90 per cent of the notes. They do not tolerate the man on the diamond who catches only 80 per cent of the balls. The standards which the student body set are high…When the world holds its examinations it will require the same standards of accuracy and honesty which the student bodies impose upon themselves. Unless the mind is brought under such training and discipline as will enable it to acquire these standards at an early period, the grave danger increases that they may never be acquired.

“It is for this reason that our secondary schools are of such great importance…While the needs of our universities are very great, and every effort should be made to meet them, it does not seem that sufficient emphasis has been placed on the needs of our secondary schools…Judge Phillips said very little concerning the scholarship of the master and his assistants, but he put a great deal of emphasis on their character. He was looking beyond the lessons of the classroom to the ‘real business of living.’

“…Next after his duty to his Maker, Samuel Phillips placed his duty to his country…But it is scarcely to be considered that he thought duty to country consisted in holding public office. He undoubtedly was concerned with the larger field of good citizenship. While it will always be necessary to give attention to the choice of public officers, if good citizenship could be made to prevail, offices would very largely look after themselves…[H]e was more interested in training young men for citizenship than in preparing them for public office. To his mind, faith in God was inseparable from faith in his country and faith in his fellow men.

“In these days, when there is so large an amount of delegated power, the danger increases that the average citizen may take too much for granted. Because the affairs of his country have been progressing satisfactorily, he may think nothing can change their course. Such is not the case. When the country makes progress it is because some one gives it careful attention and direction, and because the people are contented, industrious, and law-abiding, and as a whole are discharging their duties of citizenship.

“When the cause of the Revolution still hung in the balance, when this school was conducted in an abandoned carpenter shop, before our Federal Constitution had made our scattered Colonies into one nation, when authority was weak and all the future was uncertain, the patriots of that day offered life, fortune, and honor in defense of their country. They did not doubt; they did not complain. They went forward, placing their hope on the sure support of liberty and justice, the improvement of agriculture, industry, and commerce, and the advance of education. The day has come when we have seen their hope fulfilled, when we have seen their faith justified, and when success has demonstrated the correctness of their theories. The general advance made by our country is commensurate with the advance which has been made by Phillips Academy. As we behold it our doubts ought to be removed, our faith ought to be replenished. Our determination to make such sacrifices as are necessary for the common good ought to be strengthened. We may be certain that our country is altogether worthy of us. It will be necessary to demonstrate that we are worthy of our country.”