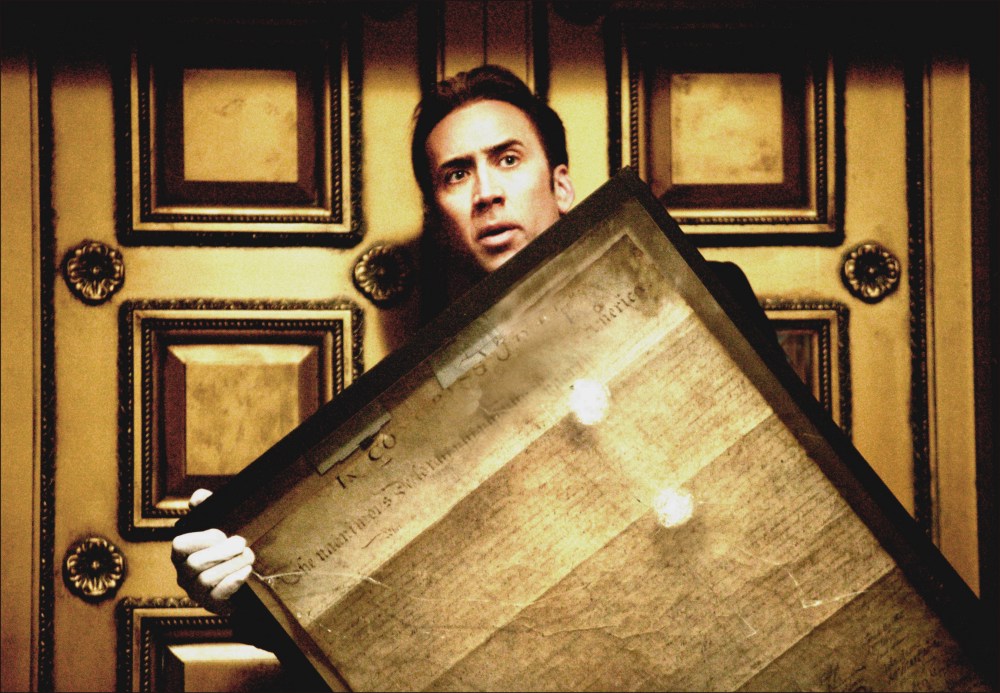

While we could venture to decipher the degrees of separation between Calvin Coolidge and Nicholas Cage, who, it is rumored, will reprise his role as Ben Gates next year in the third National Treasure film, we find that reality is both more interesting and more instructive. The original manuscripts of the Constitution and Declaration of Independence spent much of our nation’s history en route to somewhere more permanent and protected. The Declaration, being of course the older of the two, followed Congress through Pennsylvania, Maryland, New Jersey, New York and back again before coming to Washington in 1800 at the direction of President Adams. These two National treasures would move again when the British threatened the Capital and once more when the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor but 1921 found them in the papers of the State Department, under the responsibility of the new Secretary of State, Charles Evans Hughes. It was Hughes who quickly recognized the urgent need of securing those invaluable documents in a place befitting their importance. After many years of travel and duplication, especially after the “wet transfer” method inflicted on the Declaration by William J. Stone (authorized by then Secretary of State, John Quincy Adams) in 1820, the documents needed protection from light, moisture and fire. Keeping them in facilities that were anything but fireproof was unthinkable to Hughes or his chief, President Harding.

The Secretary went to Harding with an executive order approving transfer of these historic charters to the custody and care of competent archivists at the Library of Congress, where they could be displayed inside specially-designed frames in a secure yet dignified setting. The Librarian of Congress, Herbert Putnam, eagerly prepared to receive and display both manuscripts. To sell the Budget Bureau on the idea, Librarian Putnam explained how he envisioned the display would look, “There is a way…we could construct, say, on the second floor on the western side in that long open gallery a railed inclosure, material of bronze, where these documents, with one or two auxiliary documents leading up to them, could be placed, where they need not be touched by anybody but where a mere passer-by could see them, where they could be set in permanent bronze frames and where they could be protected from the natural light, lighted only by soft incandescent lamps. The result could be achieved and you would have something every visitor to Washington would wish to tell about when he returned…” A special mail truck delivered them and even before plans could be drawn up for their resting place, $12,000 in appropriations had been secured just before final estimates of the year were submitted by the Bureau in 1922.

Transferring the Declaration from the offices of the State Department to the Library of Congress, September 30, 1921.

Mail truck is loaded with the Declaration and Constitution as Herbert Putnam, standing at center in the fedora, supervises this sensitive operation. Read more at http://www.archives.gov/exhibits.charters/declaration_history.html.

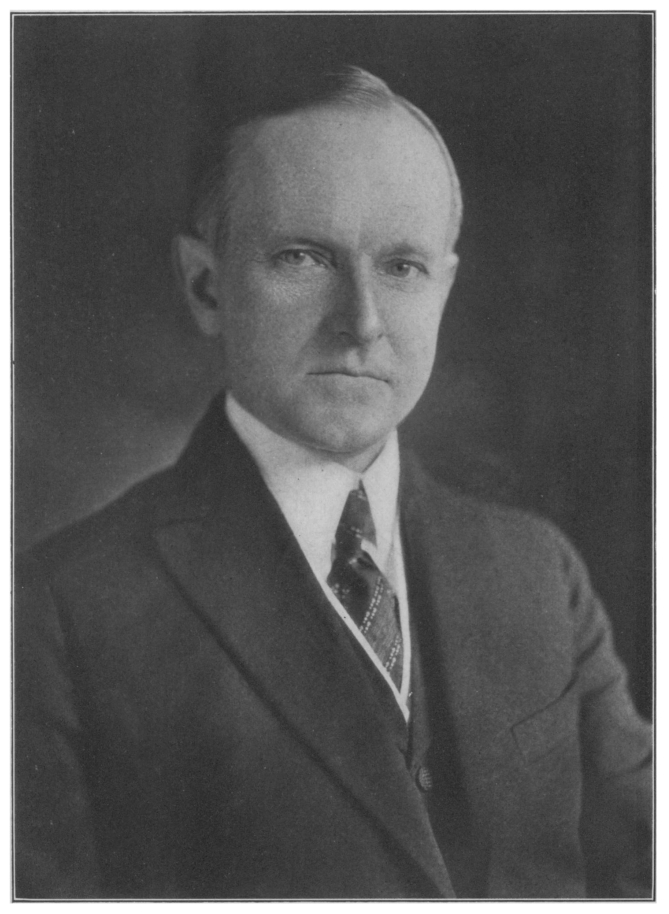

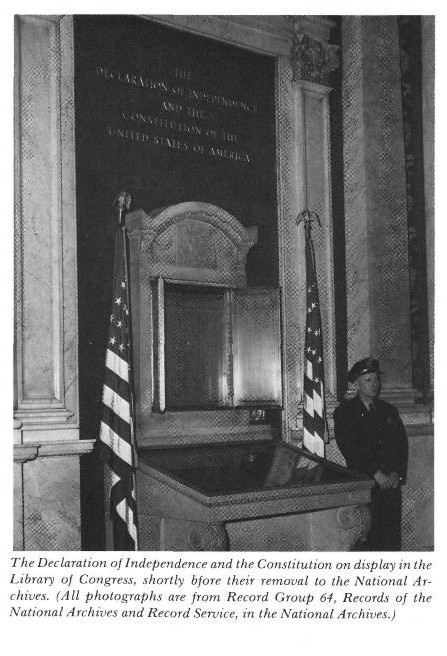

Francis H. Bacon began drawing a design for what journalists dubbed at the time, a “sort of shrine” to the great principles articulated in these two documents. It would be Bacon’s brother, Henry, who conceived the Lincoln Memorial which was dedicated in May that same year. It would not be until early 1924, however, before what was to be a suitable final resting place was ready for the Constitution and Declaration. Bronze frames with double-paned glass would house each manuscript. Between each pane of glass was placed a layer of gelatin film to block out any damage inflicted by light. Marble carefully selected from New York, Tennessee and, of course, Vermont, surrounded and supported the two bronze frames. Greek and Italian marble comprised the display’s flooring and ballustrade to match the materials in the rest of the Library. American materials only would have the closest contact with each document, however. A 24-hour guard would be placed to ensure the site remained protected. Gold-plated bronze doors would open to present the Declaration above the glass and marble case containing the Constitution. At last complete, the site would be dedicated by none other than President Calvin Coolidge, joined by Mrs. Coolidge, Secretary Hughes, Librarian of Congress Putnam, and numerous other dignitaries on February 28, 1924.

President and Mrs. Coolidge, with Mr. Putnam and others come together to ensure both documents are properly preserved for generations to come, February 28, 1924.

What struck everyone, and would distinguish that occasion from later dedication ceremonies, was its quiet simplicity. Unlike the 1952 move of that same historic pair of treasures to their current home at the National Archives, there were no elaborate ceremonies, no speeches, no troops, no Marine Corps Band. Those gathered witnessed a much humbler scene in the Great Hall of the Library of Congress on that February day in 1924. Two Library policemen held flags lowered in salute on either side of the display, raising them at the crucial moment to reveal the Declaration and Constitution viewable together at last. All remained silent as the Librarian of Congress, red-headed Herbert Putnam, stepped forward to place both documents into their respective bronze fittings. Finally a small choir of Library employees took up the familiar lines of Samuel Smith’s 1832 anthem, America. Attended by our red-headed President and Mrs. Coolidge, it was not long before many in the audience were singing along. No doubt Grace’s melodic voice stirred many present to join in that spontaneous expression of their love for America’s ideals. Together the crowd sang two stanzas and the ceremony was over. It was altogether a fitting tribute to the two greatest charters of liberty humanity has ever known.

My country, ’tis of Thee,

Sweet Land of Liberty

Of thee I sing;

Land where my fathers died,

Land of the pilgrims’ pride,

From every mountain side

Let Freedom ring.

…Our fathers’ God to Thee,

Author of Liberty,

To thee we sing,

Long may our land be bright

With Freedom’s holy light,

Protect us by thy might

Great God, our King.

From “The Empty Shrine: The Transfer of the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution to the National Archives” by Milton O. Gustafson, published in American Archivist 39.3 (July 1976): 271-285. Digitized courtesy of the Society of American Archivists at http://archivists.metapress.com/content/n50n22w711j64203/fulltext.pdf. The materials comprising this display, emptied of the Declaration and Constitution, were finally placed into storage in the late 1990s.

For further reading see also:

John Y. Cole, “The Library and the Declaration: LC Has Long History with Founding Document,” The Library of Congress, http://www.loc.gov/loc/lcib/9708/declare.html (accessed June 4, 2014).

A comic strip narrating the 1924 dedication and subsequent history at the National Archives can be found in “Flashbacks” by Patrick M. Reynolds at http://www.redrosestudio.com/Natl%20Archives.html.