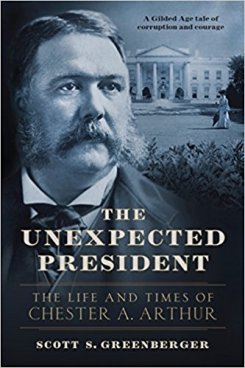

Just ahead of the one year anniversary for the publication of Mr. Greenberger’s book, we finally review “The Unexpected President” published by Da Capo Press. “Unexpected” achieves the unexpected: stepping into an era about which most Americans know nothing and consequently leaving us with a sense of its newness and color.

Many know so little about Chester Arthur – aside from those signature muttonchops – that, for many readers, learning who he was may seem like meeting a new President altogether.

Mr. Greenberger, a journalist himself, infuses the sights, sounds, smells, and feel of the places we encounter in this book, in the spirit of the descriptive reporting that defined New York’s news coverage at the Times, Sun, Tribune, and Herald during the late nineteenth century. He is the former editor of Stateline, focusing on state-related news and policy, as well as a co-author in 2009 with former Senator Tom Daschle of Critical: What We Can Do about the Health Care Crisis.

The central question is simple but profound: Can making a man President change him for the better? Does the office improve the man, carrying the potential to overcome the worst, self-serving pasts? Chester Arthur certainly had such a past, in servitude to a political clique openly employing public office for personal advantage. When Arthur succeeded to the Presidency in September 1881, it seemed certain the country would soon rush headlong into a corrupt abyss, merchandising public trust and remaking the Presidency into the likeness of New York’s political boss, the vain and promiscuous Roscoe Conkling. It was one quiet, reclusive woman, from Arthur’s own New York — Julia Sand — who refused to accept this as a foregone fate. In the first of nearly two dozen letters she wrote between 1881 and 1883, Sand answers this question resoundingly in the affirmative. It is her faith in Arthur’s ability that arrives just when it seems most needed, as then Vice President Arthur stands friendless on the cusp of succeeding the wounded Garfield. It is this faith of an unknown, regular American lady that certainly helps Arthur find the courage to do what was right, to overcome what he had become, to rekindle his moral integrity, and to serve the office and the nation, not himself or his cronies, with honor.

For those of us who study the underrated and oft undeservedly forgotten Presidents, Chester Arthur shares some remarkable similarities with another Vermonter and later tenant at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue, Calvin Coolidge. Both serving as Vice Presidents who succeeded upon the tragic deaths of their predecessors, they possessed an abiding reverence for the Office. Both emptied themselves to serve the whole people, knowing fully that the people had not elected them. Of course, in Coolidge’s case, they would enthusiastically do so the following year of his tenure. Both understood the somber, lonely duty the Office extracted and they still poured everything they had into its obligations. The Office demanded the best they had to give and they gave all in keeping with the sacred oath they would take as Presidents. Remarkably, both took the oath of office at around the same early morning hour, though in very different settings forty-two years apart. Both lawyers by profession, Arthur would enter the New York bureaucracy while Coolidge would steadily earn promotion in the state government of Massachusetts. Both would take office after the taint of public scandal and political corruption had impacted members of their own party, in Arthur’s case…his own association with Conkling. Both would experience the loss of a son and, in Arthur’s case, a wife as well. The intense grief would not incapacitate either man when the need to serve summoned. Still, the Office would carry a heavy toll on both men, arguably hastening their own deaths at ages 57 (Arthur) and 60 (Coolidge). They were unafraid to exercise the veto power to check Congressional pork spending, even more remarkable for Arthur whose life had been built upon perpetuating that very system. They dissented on the limitation of immigration, especially from the Far East, but recognized the constitutional authority Congress possessed to legislate in that field. They understood their limitations and knew themselves well enough to recognize power is deceptive, fame is fleeting, and no leader is indispensable. They knew when to leave, as gentlemen do. They left the nation better than they came to it but neither cherished much concern for their legacies. This presents hardship at times for the historian but it leaves us admiring the men all the more.

We agree with Mr. Greenberger that the Gilded Age is severely misunderstood and unknown. It seems so foreign to us not so much because it is unstudied (though, it is!) but because the era has been characterized for us as unworthy of our attentions for too long by the supposedly larger, more challenging events of the twentieth century. Such ingrained emphasis on what came after (as if that were the starting point of history) remains a disservice to our comprehension of events unfolding now and yet to unfurl in the future. It was in the latter half of the nineteenth century that much of the form and character of the America we know developed. The War of 1861-1865 changed what the nation would be forever but it was in Reconstruction and its aftermath, the Gilded Age, that we would define what we are and who we will be in fundamental ways. Like the Presidency, can America change what it is? To work out the ongoing obligations of citizenship, we will find the task impossible of perspective if we do not reckon honestly with the Gilded Era.

Though no book can do everything, Mr. Greenberger’s “The Unexpected President” is a popular history and as such does not venture into a detailed discussion of the policies and particulars of President Arthur’s administration: from modernizing the U.S. Navy, implementing genuine civil service reform, to facing the immigration debate raging even then. A welcome care is shown by the author for the primary source material and with only a few exceptions, does he deviate from this respect (though Julia Sand’s frankly unknown views about the 1883 Supreme Court repudiation of the 1875 Civil Rights Act is a conspicuous exception). Arthur certainly saw what was coming in 1884, with his own retirement and the election of Grover Cleveland, the first Democrat President since James Buchanan in 1856. Arthur observed greater courage in Cleveland and admired it, a courage that extended to a public association with freedmen like Frederick Douglass and his wife at official functions (something neither Garfield nor Arthur were willing to do). When tackling perhaps the least known President of the latter half of the nineteenth century, one cannot avoid relying substantially on the scholarship of Arthur’s leading biographer, Thomas C. Reeves, as the author freely acknowledges. Mr. Greenberger slides past much of the drama surrounding Garfield’s assassination and his subsequent, slow decline, leaving those to Candice Millard (whose 2011 Destiny of the Republic reintroduces Reeves’ discovery of Julia Sand and her letters to President Arthur). Having been over forty years since Reeves’ biography of Arthur, the author introduces to us a virtually brand new study. It is unfortunate, however, that the author declines to reference equally insightful and important studies by Michael J. Gerhardt (who devotes an entire chapter in his The Forgotten Presidents: Their Untold Constitutional Legacy to Chester Arthur) and Jean Edward Smith (whose biography Grant published in 2001). Smith documents President Grant’s substantial achievements on civil rights, reduction of the nation’s debt, return to solvent finances, and his pivotal role as a peacemaker when the nation needed healing after four terrible years of War and four more of Congressionally-imposed Reconstruction. Unfortunately, in “The Unexpected President,” Grant is only seen through the eyes of the basic narrative about him (reinforced by a few sideways frowns from Julia Sand). Grant’s fault, like Coolidge’s predecessor Harding, was not personal corruption but a trusting loyalty in untrustworthy subordinates who lived Arthur’s pre-White House credo. That Arthur himself would condemn them in keeping with the honor due the Office is the timeless and inspiring reminder of Mr. Greenberger’s fine book.

“The Unexpected President” has a welcome place in a renewed study of America’s forgotten past, especially the Gilded Age. That era, like Calvin Coolidge’s Roaring Twenties, reminds us that the nation is best served when our leaders empty self, earning honor not for what they receive but for what they give. By upholding their oath, revering the Office, and validating the faith regular citizens reposed in them, the legacies of Presidents like Arthur and Coolidge shine brighter when others tarnish with time.