“In Massachusetts the 19th of April is known as Patriots Day. It is honored and set apart. The whole Nation is coming more and more to observe it. As the time lengthens from the occurrences of 1775, its significance becomes more apparent and its importance more real. It stands out as one of the great days in history, not because it can be said the American Revolution actually began there, but because on that occasion it became apparent that the patriots were determined to defend their rights.”

“The Revolutionary period has always appeared to me to be significant for three definite reasons. The people of that day had ideals for the advancement of human welfare. They kept their ideals within the bounds of what was practical, according to the results of past experience. They did not hesitate to make the necessary sacrifice to establish those ideals in a workable form of political institutions. As I have examined the record of your society, I believe that it is devoted to the same principles of practical idealism enshrined in institutions by sacrifice.”

Grace Coolidge leading by example, completes her absentee ballot on the White House lawn, while she urges all Americans to get out and vote in that year’s election, 1924.

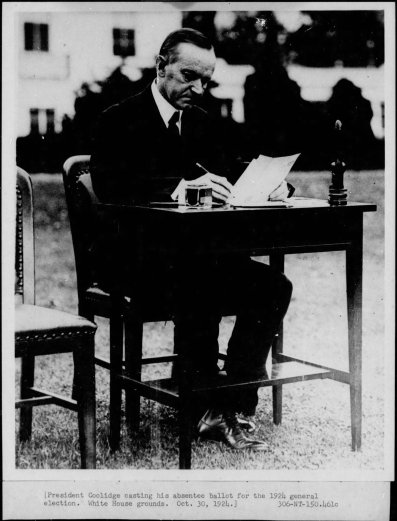

Calvin likewise, filling out his absentee ballot in front of the White House, encourages everyone eligible to exercise an informed choice at the ballot box.

These words, given before the Daughters of the American Revolution on April 19, 1926 by President Calvin Coolidge, underscored that the principles which fueled the fight for independence were neither abstract concepts nor rigged systems of thought to consolidate power in the hands of a few men, at the expense of all individuals, including women. As Coolidge continued,

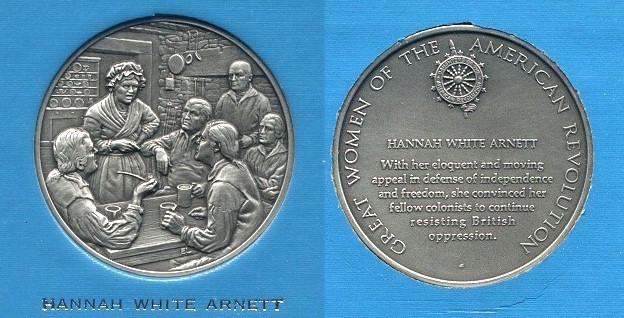

“This is but the natural inheritance of those who are descended from Revolutionary times. In this day, with our broadened view of the importance of women in working out the destiny of mankind, there will be none to deny that as there were fathers in our Republic so there were mothers.” Cokie Roberts was hardly the first to recognize and praise this all too obvious truth. As Coolidge goes on, “If they did not take part in the formal deliberations, yet by their abiding faith they inspired and encouraged the men; by their sacrifice they performed their part in the struggle out of which came our country. We read of the flaming plea of Hannah Arnett, which she made on a dreary day in December, 1776, when Lord Cornwallis, victorious at Fort Lee, held a strategic position in New Jersey. A group of the Revolutionists, weary and discouraged, were discussing the advisability of giving up the struggle. Casting aside the proprieties which forbade a woman to interfere in the counsels of men, Hannah Arnett proclaimed her faith. In eloquent words, which at once shamed and stung to action, she convinced her husband and his companions that righteousness must win.”

Hannah was not some isolated instance, though, in a supposedly chauvinistic society, as Coolidge points next to others, some named and many more unnamed who shared in the burdens of freedom. “Who has not heard of Molly Pitcher, whose heroic services at the Battle of Monmouth helped the sorely tried army of George Washington! We have been told of the unselfish devotion of the women who gave their own warm garments to fashion clothing for the suffering Continental Army during the bitter winter of Valley Forge. The burdens of the war were not all borne by the men.”

The President would go on to commend the laudable record and work by the Daughters of the American Revolution for carrying on out of a wisely crafted charter and many acts of service the practical ideals of that Revolutionary generation of men and women. Yet, who could assert that in a Republic the work of one generation is adequate? To continue a free people with republican institutions, the sacrifice of each citizen of every generation is necessary for liberty to last. “Our Republic gives to its citizens greater opportunities, and under it they have achieved greater blessings than ever came to any other people. It is exceedingly wholesome to stop and contemplate that undisputed fact from time to time.” As a corollary to this apparent realization, it becomes necessary that if so many good things are to continue to be enjoyed, it demands “a corresponding service and sacrifice. Citizenship in America is not a private enterprise, but a public function.” None of us can opt out of our duty to vote and still reasonably expect someone else will execute what is ours to exercise. When we refuse to exercise the duties of freedom, we will soon find ourselves severed from the benefits that inseparably accompany them. It short, “disaster will overtake the whole fabric of our institutions.” Participation is the heart of our Republic. “If we are to maintain the principle that governments derive their just powers from the consent of the governed, if we are to have any measure of self-government, if the voice of the people is to rule, if representatives are truly to reflect the popular will, it is altogether necessary that in each election there should be a fairly full participation by all the qualified voters.” Put another way, if we do not participate in the direction of America, that choice will be made for us, usually without our consent and against those principles for which we would vote as informed individuals. As Phyllis Shlafly once put it, our vote is to be a choice, not an echo.

Coolidge did not have much to commend on the participation of voters, even after the victory for woman’s suffrage went into effect just before the 1920 election. “It was hoped,” the President noted, “that giving the vote to women would arouse a more general interest in the obligations of election day. That has not yet proved to be the case.” Calculations from 1920 found that out of some 27 million votes cast, only 37 per cent represented the votes of women. While Coolidge knew that blaming women for failing to exercise so recently recognized a privilege was not entirely fair, yet he understood that it was symptomatic of an even more serious problem when the voter disenfranchises herself or himself by simply not showing up. It remained a “startling fact that in the past two presidential elections [1920 and 1924] barely 50 per cent of those qualified to vote have done so.”

President Coolidge signs the “Nation’s Birthday Book” and the Patriot’s Pledge of Faith, standing with 13 women of the Sesquicentennial and Thomas Jefferson Centennial Commissions seeking to purchase and preserve Monticello, May-June 1926.

Returning to the practical idealism of our Revolutionary generation, Coolidge believed that the solution would be found not in legal disenfranchisement or punitive action but in “all bodies of men and women interested in the welfare of his country to join together under some efficient form of organization to correct this evil which has been coming on us for more than 40 years, but which within the last decade has become most acute.” This is what made the Daughters of the American Revolution so pivotal a contributor to real results in the future of the country. It was not for lack of effort that turnout was declining — as the President made clear in the very next statement — praising the work of numerous volunteer efforts from the National Civic Federation, the National League of Women Voters and many other citizen groups banding together to inform and inspire all Americans to get involved, using the power each citizen already possesses through the ballot box to express one’s will in public decisions. Yet, Coolidge saw the glass not as half empty but as fuller than it would have been had not all of these worthy efforts been made to educate civic responsibilities. Numbers were already revealing that most of the world’s leading nations had far higher voter rates that ours. Even Italy produced more involvement.

Coolidge was not indulging the forces that find fault in America because it has not lived up to some unrealistic definition of perfection, he was urging every man and woman to embrace the duty that goes hand in hand with freedom. What made the indifference toward voting so perilous was its “insidiousness,” the subtle illusion that no harm is inflicted on the future by sitting out the election. In actuality, by abstaining, our interests and choices — the popular will — go unrepresented every time we decline to vote. We need not fear that faith in our foundations is somehow invalidated. The people, even in the gravest emergencies, prove worthy of self-government. “It is only the approach of some silent and unrecognized peril that needs to give us alarm. Such a situation will develop if the Government ceases to represent the people because the public has become inarticulate…But if the people fail to vote, a government will be developed which is not their government.”

Notice the woman next to President Coolidge’s left is his Assistant Attorney General, Mabel Willebrandt.

As Coolidge summarizes to the Daughters of the American Revolution gathered on this day eighty-eight years ago, “This is not a partisan question, but a patriotic question. Your society, which is organized ‘to cherish, maintain, and extend the institutions of American freedom,’ may well take a leading part in arousing public sentiment to the peril that arises when the average citizen fails to vote…The whole system of American Government rests on the ballot box. Unless citizens perform their duties there, such a system of government is doomed to failure.”

If we stay home this year – 2014 – what is to say America will not pass that point of no return, the failure of which Coolidge warned, a future shut off forever from that “second chance” to assert the power that was always ours but having been abdicated for so long, now rests with others insulated from and unaccountable to our choice, our consent and our control.