Addressing those assembled at Arlington National Cemetery, May 30, 1924, President Coolidge spoke,

“American citizenship is a high estate. He who holds it is the peer of kings. It has been secured only by untold toil and effort. It will be maintained by no other method. It demands the best that men and women have to give. But it likewise awards to its partakers the best that there is on earth. To attempt to turn it into a thing of ease and inaction would be only to debase it. To cease to struggle and toil and sacrifice for it is not only to cease to be worthy of it but is to start a retreat toward barbarism. No matter what others may say, no matter what others may do, this is the stand that those must maintain who are worthy to be called Americans.”

During the Coolidge presidency, there were nine individuals whose actions merited the Medal of Honor, the highest recognition to those who distinguish themselves while wearing the uniform. Their actions were not all combat-related, as the years between 1923 and 1929 was a time of peace. Their courage and selfless service, however, be it in behalf of their brothers-in-arms, those around the world in need, or in the cause of greater possibilities (with nothing but uncertain flying crafts and their navigational skills) were testaments to what President Coolidge referred — those “worthy to be called Americans.” That tradition of selfless service will continue unbroken and it remains, rightly so, a reason to honor and aspire to those worthy of the name “American” to this day.

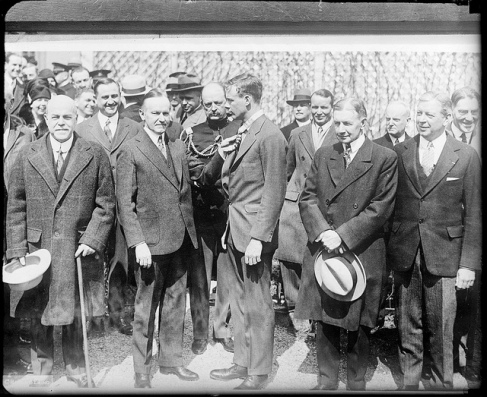

President Coolidge awarding the Medal of Honor to Machinist Floyd Bennett, USN (in front of him) and Commander Richard E. Byrd, Jr., USN (behind Coolidge), for their courageous risk of life in the first “heavier than air flight” to and from the North Pole in a tri-motor Fokker F-VII called the Josephine Ford.

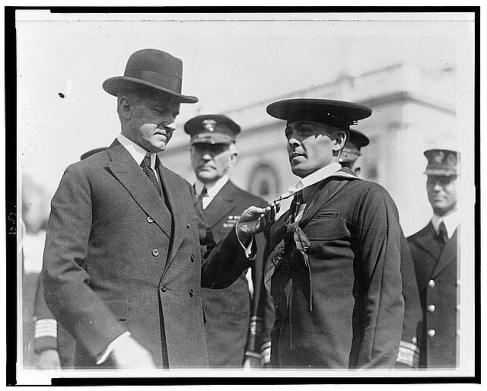

The awarding of the Medal of Honor to Torpedoman Second Class Henry Breault, USN, for his quick actions to rescue a shipmate in their submarine 0-5, which sank within one minute. Confined by the hatch that closed after him, he kept himself and his mate alive for thirty-one hours below the surface until rescued.

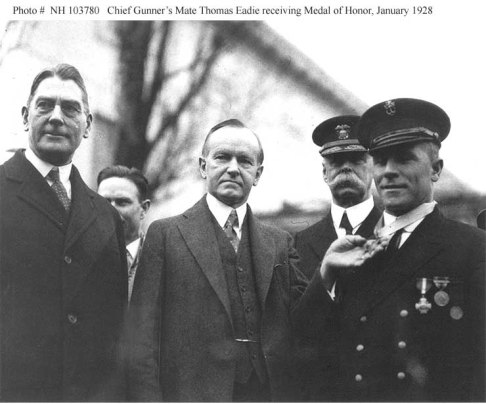

Chief Gunner’s Mate Thomas Eadie, USN, received the Medal of Honor for an extraordinary rescue of his shipmate, Chief Torpedoman Michels, whose line fouled 102 feet below while trying to connect an airline to the sub USS S-4. CGM Eadie (as his citation states) “knowingly took his life in his hands,” diving down to skillfully extract Michels, bringing them both back to the surface after two hours of heroic effort.

Lieutenant Commander Walter Atlee Edwards, USN, was awarded the Medal of Honor for his rescue of 482 men, women and children from the sinking French transport Vinh-Long, while aflame in the Sea of Marmora, off the coast of Turkey. While commanding the USS Bainbridge, he placed and kept his ship alongside the burning wreck until all alive were safely transferred to the American vessel.

Machinist’s Mate William Russell Huber, USN, was recognized here with the Medal of Honor for his exceptional heroism after a boiler exploded aboard the USS Bruce in Norfolk Navy Yard, 11 June 1928, he went into the “steam-filled fireroom and at grave risk to his life” successfully carried shipmate, Charles H. Bryan, to safety. Machinist’s Mate Huber went below again to aid in removing others from the room despite suffering severe burns to his arms and neck.

Captain Charles A. Lindbergh, Army Air Corps Reserve, was recognized with the Medal of Honor for both courage and skill despite the risk in navigating by nonstop flight from New York City to Paris, France, in the Spirit of St. Louis, a custom-built single-engine monoplane, achieving (as his citation, held here by President Coolidge, states) “not only…the greatest individual triumph of any American citizen but demonstrated that travel across the ocean by aircraft was possible.”

Ensign Thomas John Ryan, USN, was presented with the Medal of Honor for heroism in rescue of a woman trapped when fire broke out at the Grand Hotel in Yokohama, Japan, September 1, 1923, as the result of an earthquake that hit the city. Ensign Ryan disregarded his own safety to help another, as unexpected events demanded decisive action.

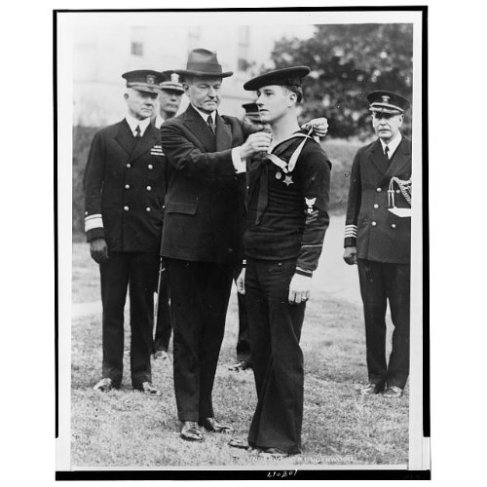

Here is First Lieutenant Christian Frank Schilt, USMC, to whom the President has just given the Medal of Honor for his superb actions in Quilali, Nicaragua, over the course of three grueling days in January 1928. First Lieutenant Schilt, following an intense fight to restore peace to the area, volunteered to evacuate all of the wounded by air and bring in a new commanding officer as relief. Taking off a total of ten times while under steady enemy fire from rough urban terrain, he removed all the wounded, saved three lives and brought back the necessary supplies to those in dire need on the ground.