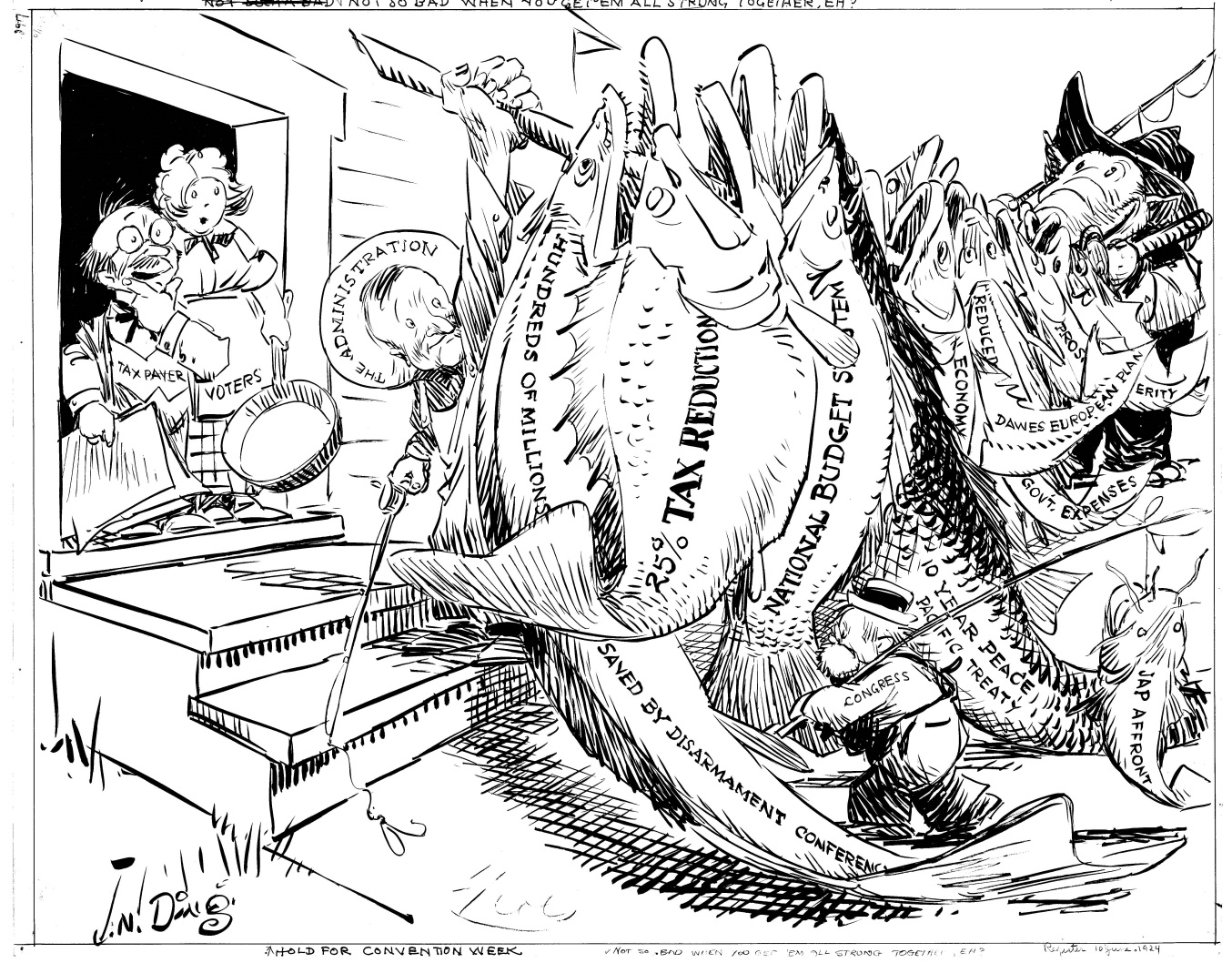

Glaringly absent from most of today’s training in political leadership is a straightforward connection to reality. For all too many, the money for each and every appropriation, political favor, or tax exacted will always be there upon demand. There is no realization that every time a tax goes up, someone has to work harder in order to pay it. Insulated from the outcomes of their own actions, most politicians fail to grasp what crushing price they inflict on the very people who create, work and struggle to produce in this country. Not so with Calvin Coolidge. Coolidge was instilled with a recognition of this inescapable truth from a very young age. It remained present in every act of his public life. “As I went about with my father when he collected taxes, I knew that when taxes were laid some one had to work to earn the money to pay them. I saw that a public debt was a burden on all the people in a community…” From this “good working knowledge of the practical side of government” Calvin understood that individual freedom and opportunity suffer in proportion to government taxation.

As Vice President, Coolidge knew that business is not the immortal “golden goose” to be raided infinitely by government whim. He knew this not as an academic abstraction or politician’s platitude but from working the country store back in Plymouth. “The business of the country, as a whole, is transacted on a small margin of profit,” he reminded his audience. The notion that profit was to be confiscated and “windfalls” penalized had even then been a fashionable demand during his youth. “The economic structure is one of great delicacy and sensitiveness. When taxes become too burdensome, either the price of commodities has to be raised to a point at which consumption is so diminished as greatly to curtail production, or so much of the returns from industry is required by the government that production becomes unprofitable and ceases for that reason. In either case there is depression, lack of employment, idleness of investment and of the wage-earner, with the long line of attendant want and suffering on the part of the people.” Then Coolidge zeroes in on the principle at stake, “After order and liberty, economy is one of the highest essentials of a free government.”

Experience confirmed the soundness of this precept time and again, as he would confirm, even more emphatically, two years later during his Inaugural Address, “The collection of any taxes which are not absolutely required, which do not beyond reasonable doubt contribute to the public welfare, is only a species of legalized larceny. Under this republic the rewards of industry belong to those who earn them. The only constitutional tax is the tax which ministers to public necessity. The property of the country belongs to the people of the country. Their title is absolute. They do not support any privileged class; they do not need to maintain great military forces; they ought not to be burdened with a great array of public employees…” Then, taking on the issue of punitive taxation directly, he said, “I am opposed to extremely high rates, because they produce little or no revenue, because they are bad for the country, and, finally, because they are wrong. We can not finance the country, we can not improve social conditions, through any system of injustice, even if we attempt to inflict it upon the rich. Those who suffer the most harm will be the poor.”

Keenly aware that “the power to tax is the power to destroy,” he summarized the essence of the matter at Memorial Continental Hall in June 1924, “A government which lays taxes on the people not required by urgent public necessity and sound public policy is not a protector of liberty, but an instrument of tyranny. It condemns the citizen to servitude. One of the first signs of the breaking down of a free government is a disregard by the taxing power of the right of the people to their own property. It makes little difference whether such a condition is brought about through will of a dictator, through the power of a military force, or through the pressure of a organized minority. The result is the same. Unless the people can enjoy that reasonable security in the possession of their property, which is guaranteed in the Constitution, against unreasonable taxation, freedom is at an end. The common man is restrained and hampered in his ability to secure food and clothing and shelter. His wages are decreased, his hours are lengthened. Against the recurring tendency in this direction there must be interposed the constant effort of an informed electorate and of patriotic public servants. The importance of a constant reiteration of these principles cannot be overestimated.”