It matters not what era or generation we find ourselves, there is an irrepressible impulse to search for and take pride in exceptional deeds, heroic achievements and great examples of character, courage and competence. As Americans we especially prize the opportunity to honor noble men and women. It reminds us that good is still rewarded and it renews our faith. Such was the occasion eighty-seven years ago, when young Charles Lindbergh completed the first ever solo transatlantic flight, a 3,600 mile, 33 and a half-hour feat, from Roosevelt Field in New York to Le Bourge Field, outside Paris, on May 20-21, 1927.

It matters not what era or generation we find ourselves, there is an irrepressible impulse to search for and take pride in exceptional deeds, heroic achievements and great examples of character, courage and competence. As Americans we especially prize the opportunity to honor noble men and women. It reminds us that good is still rewarded and it renews our faith. Such was the occasion eighty-seven years ago, when young Charles Lindbergh completed the first ever solo transatlantic flight, a 3,600 mile, 33 and a half-hour feat, from Roosevelt Field in New York to Le Bourge Field, outside Paris, on May 20-21, 1927.

Returning to his homeland, Colonel Lindbergh found a nation ready to recognize what he had done not only for its contributions to aviation but to a much larger degree how he furnished a front-page opportunity to take stock of what was really good and worthwhile about America. Not unlike today, Americans had heard enough negativity and criticism of their ways, their institutions, their shortcomings. Too little regard had been given to her accomplishments, to the things that were genuinely wholesome, admirable and worthy of praise when it came to America. Americans, then as now, loved their country and wanted others to better understand why that love remained justified. It was more than a chance to display scientific acumen, to gloat at what others had failed to do, it was a time to manifest good will, charity and service, especially as the people of France mourned the loss of the two pilots (Charles Nungesser and Francois Coli) sent westward to complete the same challenge just 13 days before Lindbergh’s arrival in Paris. It was not a time to flaunt greatness for its own sake, it was a time to commend bravery and ingenuity in the midst of tangible danger. It was a celebration of what was best about America, not with militaristic nationalism, but with humble circumspection and joy at reaching a human goal that had been years in the striving.

The occasion that bestowed the Distinguished Flying Cross, a medal signed into existence by President Coolidge the summer before, on Colonel Lindbergh was not the result of one man or one city, it was the product of some of America’s finest engineers and innovators, like Fred Rohr, whose design of the fuel system for The Spirit of St. Louis made greater distances reachable for the first time. It was the people of San Diego and the determined folks of Ryan Airlines, who turned a tuna cannery into the creator of one of the most exceptional planes ever constructed. They met Lindbergh’s sixty day deadline, spending hundreds of thousands less than the forest of competitors rushing to build the plane that would make the crossing. It was creative minds like those of Donald Hall, the chief engineer for Lindy’s plane, who devised a way to furnish enough lift despite a fuel load heavier than the aircraft itself. On and on the list could go, recounting the great deeds of those who dreamed big dreams, dared to test the bounds of the possible, and finally reaped the rewards and the risks of what had never been done before but now could be thanks in no small part to America’s freedoms and opportunities.

Welcoming this young American home, President Coolidge addressed the 100,000 gathered on this day on the north side of the Washington monument:

“My Fellow Countrymen:

“It was in America that the modern art of flying heavier-than-air machines was first developed. As the experiments became successful, the airplane was devoted to practical purposes. It has been adapted to commerce in the transportation of passengers and mail and used for national defense by our land and sea forces. Beginning with a limited flying radius, its length has been gradually extended. We have made many flying records. Our Army flyers have circumnavigated the globe. One of our Navy men started from California and flew far enough to have reached Hawaii, but being off his course landed in the water. Another officer of the Navy has flown to the North Pole. Our own country has been traversed from shore to shore in a single flight.

“It had been apparent for some time that the next great feat in the air would be a continuous flight from the mainland of America to the mainland of Europe. Two courageous Frenchmen made the reverse attempt and passed to a fate that is as yet unknown. Others were speeding their preparations to make the trial, but it remained for an unknown youth to tempt the elements and win. It is the same story of valor and victory by a son of the people that shines through every page of American history.

“The absence of self-acclaim, the refusal to become commercialized, which has marked the conduct of this sincere and genuine exemplar of fine and noble virtues, has endeared him to everyone. He has returned unspoiled. Particularly has it been delightful to have him refer to his airplane as somehow possessing a personality and being equally entitled to credit with himself, for we are proud that in every particular this silent partner represented American genius and industry. I am told that more than 100 separate companies furnished materials, parts, or service in its construction.

“And now, my fellow citizens, this young man has returned. He is here. He has brought his unsullied fame home. It is our great privilege to welcome back to his native land, on behalf of his own people, who have a deep affection for him and have been thrilled by this splendid achievement, a colonel of the United States Officers’ Reserve Corps, an illustrious citizen of our Republic, a conqueror of the air and strengthener of the ties which bind us to our sister nations across the sea, and, as President of the United States, I bestow the distinguished flying cross, as a symbol of appreciation for what he is and what he has done, upon Colonel Charles A. Lindbergh.”

Created from section 12 of the Air Corps Act on July 2, 1926, the eventual design was completed by Miss Elizabeth Will and A. E. DuBois of the Army’s Heraldic Section (now called the Institute of Heraldry), who integrated the symbolism of a cross for sacrifice, superimposed with four propellers and completed by five sun rays in each angle of the cross to denote the greatness of the deeds for which it would be bestowed. Finally the red, white and blue drawn from our national colors completes the distinctive yet simple appearance of the medal. Despite criticism of the design by those who did more than most to champion its creation, the rank and file soldier, Marine, sailor and airman always had a strong affection for it. Consequently, despite pressure to alter it, the original design has remained unchanged since its inception eighty-eight years ago.

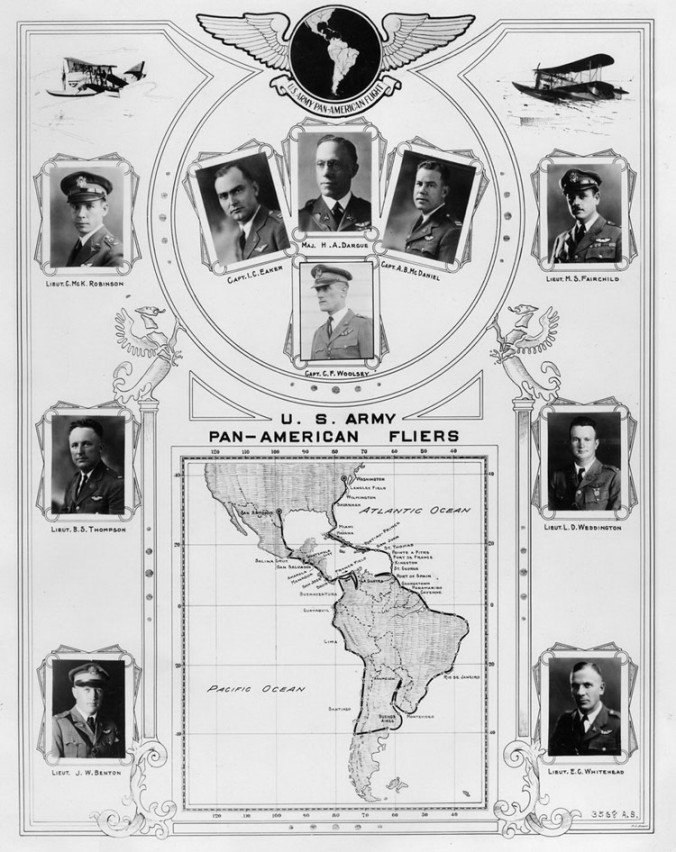

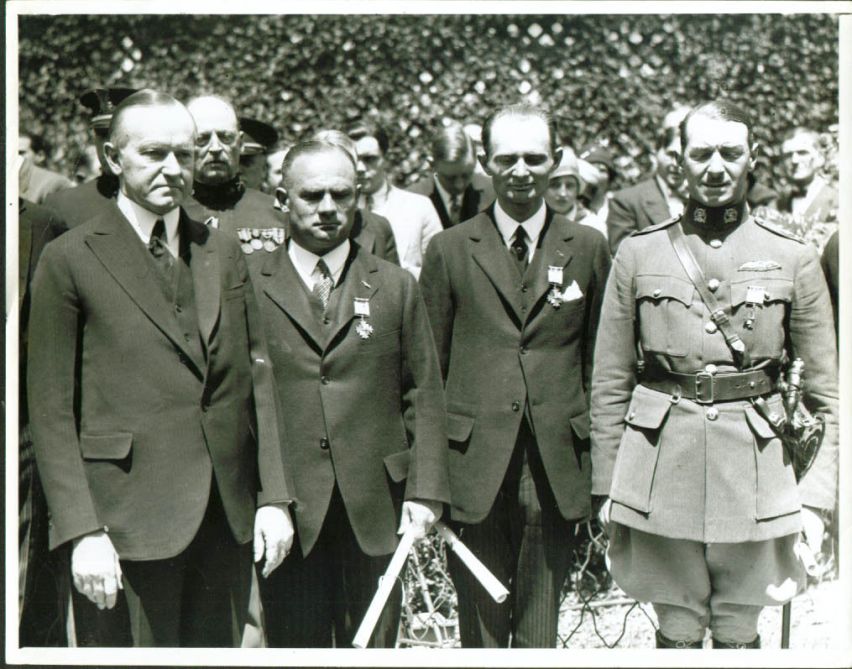

While Lindbergh was the first to receive the Distinguished Flying Cross in medal form on June 11, he was not the first to receive the citation, as the ten pilots of the Pan-American Goodwill flight of 1926 were, seen here. Lindbergh would join a vast assembly of aviators, inventors and entrepreneurs, before and after him, who would take on the unknown and leave their mark on the development of flight. As Coolidge would recount, from the earliest efforts of Wilbur and Orville Wright, along the shores of Kitty Hawk on December 17, 1903, to the circumnavigation of the globe by Major Frederick L. Martin in 1924, the effort to make flight attainable came through much trial and error, failure and success. Commander John Rodgers would begin a transpacific crossing in 1925 and be rescued after ten days at sea off the coast of Hawaii. Commander Richard E. Byrd, joined by Warrant Officer Floyd Bennett, would fly over the North Pole on May 9, 1926. The first shore to shore non-stop flight would be done by Lieutenants John A. Macready and Oakley Kelly from New York to San Diego in May 1923. After signing the legislation that created the Distinguished Flying Cross, President Coolidge would recognize upwards of fifty-eight aviators between 1927 and 1929 whose “act of heroism or extraordinary achievement” merited the honor.

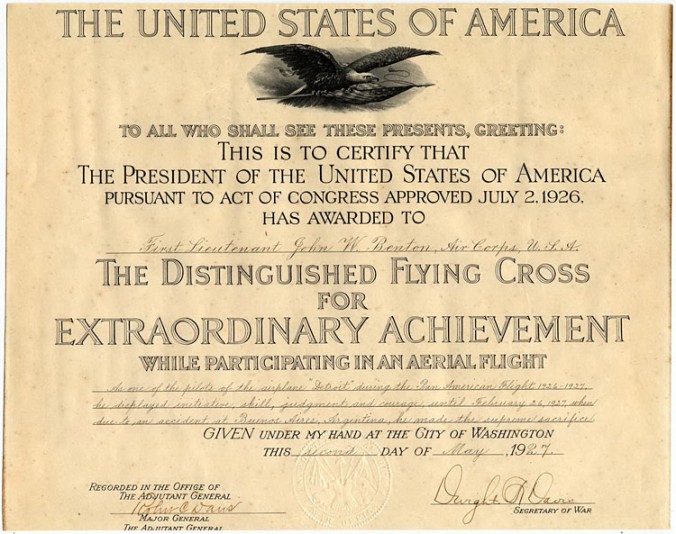

President Coolidge gave the Distinguished Flying Cross certificate for the first time just over a month before the Lindbergh ceremony. Here, at Bolling Field in Washington, Major Herbert A. Dargue accepts one of the ten awards bestowed that day, May 2, 1927. Two would be given posthumously in recognition of Captain Clinton Woolsey and Lieutenant John Benton, who tragically died from collision with another of the 5 ships participating in the Pan-American Goodwill Flight, February 26, 1927.

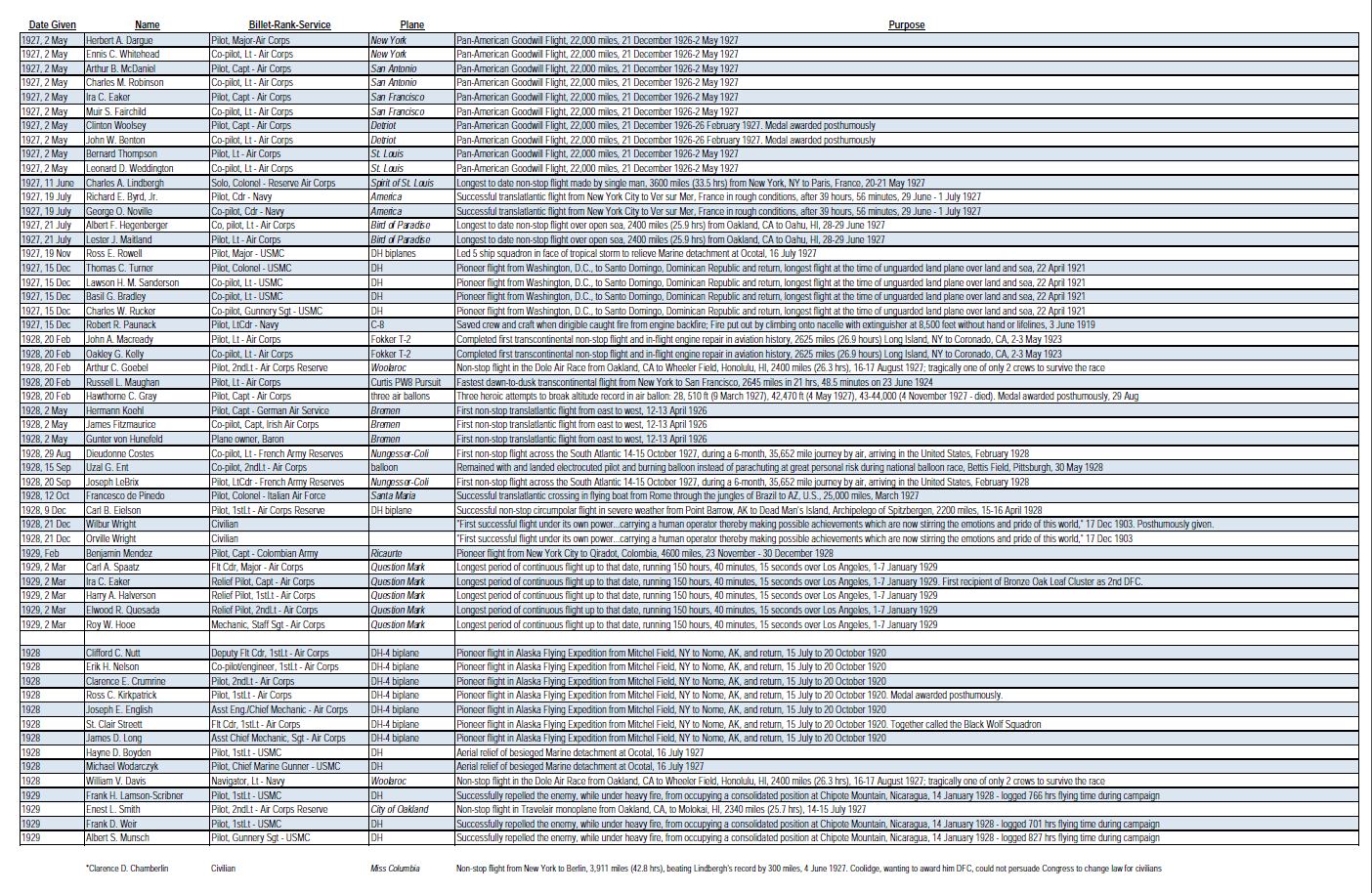

Here is a working list of the 56 individuals who were awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross during the Coolidge years. Many are not on this list including those who flew operations during this time period but were recognized after Coolidge’s term of office ended and certain civilians to whom the award was granted prior to revision of section 12 of the Air Commerce Act by Coolidge’s Executive Order 4601 effective March 1, 1927. As best research confirms the names are in chronological order by date of award, with a second list noting known recipients by year only. The name at the bottom is one whom the President tried unsuccessfully to have approved for the medal by Congress. Mr. Chamberlin declined the requirement of qualification: joining either the Air Corps or Navy as an aviator. As such he was never awarded the DFC. Also absent from this list are the tanker crews who collaborated in the endurance tests of Question Mark but failed to receive official recognition until 1976.

Lieutenant John W. Benton’s Distinguished Flying Cross citation, May 2, 1927, representative of what was given by President Coolidge to the aviators of the Goodwill flight that day.

As pointed out by the Distinguished Flying Cross Society, the law contained three fascinating elements in awarding the DFC:

1. The medal could be bestowed retroactively, as would be done by Coolidge for the Wright brothers, who were recognized on December 18, 1928. Wilbur received it posthumously, having died in 1912. Orville, still alive, would meet Lindbergh and take an active part in the Civil Aeronautics Conference in 1928. Many would carry out their work in aviation during the early 1920s but not be honored until after Coolidge’s time.

2. The medal was not predicated upon combat heroism, it placed an equal esteem for heroism in peacetime. Of the fifty-six given under the Coolidge administration, the vast majority would be for actions done outside of hostilities. James Doolittle would earn his first two Flying Crosses for the first cross-country flight in 1922 and work with acceleration in 1924 but not be officially recognized until August 1, 1929. For the first endurance record, logging 150 hours in air, all five crewmen of the Question Mark would be given the Flying Cross as one of Coolidge’s last official acts in January 1929. Even aviators of other countries were recognized with the medal for their pioneering work, such as Captains Hermann Koehl and James Fitzmaurice with Baron von Hunefeld, who were the first to cross the Atlantic from Europe to America eleven months after Lindbergh landed in Paris.

Captain James Fitzmaurice of Ireland being presented with the Distinguished Flying Cross by President Calvin Coolidge, at noon on May 2, 1928.

Coolidge also recognized Captain Koehl of Germany and the owner of the Bremer, Baron von Hunefeld (between Koehl and Fitzmaurice), with Flying Crosses for making the trek jointly thereby becoming the first to successfully cross the Atlantic from east to west and proving that in spite of stiffer wind patterns travel could go both ways by air.

3. The medal was the first to be universal to all branches of the service. Up to then, medals were distinct to the specific part of the military to which one was attached. The Distinguished Flying Cross, representing sacrifice and flight, is not only the oldest military aviation medal but, perhaps more than any other, encapsulates America. In a unique way the medal brought down artificial barriers and reminded us of our obligations to others, celebrating what is best about our country and most noble in human nature itself. Maybe that is why Coolidge liked it so much. He understood more enduring good could be secured not by fixating on her imperfections but by reflecting on the reasons America inspires and remains worthy of respect and admiration. If our nation was to improve, it remained with us not to tear down but build up, not nurse old hatreds and envies but contribute by first being better people, better neighbors, and better citizens ourselves.

Lindbergh and his mother hosted by the Coolidges at DuPont Circle, where the President and his wife stayed during repairs to the White House roof that spring of 1927. Notice how everyone is cheerful except the unexpectedly sober figure on the right. Lindbergh, about to appear in a light suit, was corrected by Coolidge who chose a dark suit for him as better befitting the formality of the occasion. Even returning heroes need to take care of the way they dress. They set a deeper example than even they may realize. It is one that should not be treated flippantly.