No, it is not in Washington, D.C., but rests across the continent among the ancient forests of California. Declared by President Calvin Coolidge in 1926 to be the “Nation’s Christmas Tree” the “General Grant” sequoia in California’s Kings Canyon National Park is the third largest tree in the world, behind “General Sherman” and “President,” named for Warren Harding in 1923. This very deliberate designation for a tree as far removed as possible from the Nation’s capital underscores where our thirtieth President placed American identity: among the People themselves, not under an omnipresent shadow of Government. Estimated at over 1600 years of age, the tree stands 267 feet in height and 107.6 feet in circumference.

The “Nation’s Christmas Tree” in the middle of summer. The snow on the ground reminds us how aptly named it was by President Coolidge. It is here, in the majesty of America’s sequoias, that the Christmas Tree finds its most distinctive representation.

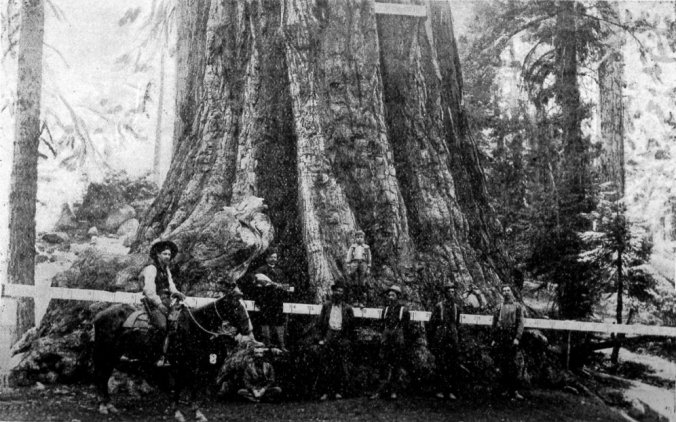

As documented by James C. Clark in his book, Presidents in Florida, this picture of another very big tree was widely circulated soon after President Coolidge’s visit to the Lake Wales area in February 1929 despite being a case of doctored photography. The superimposed image of the Coolidges beside the 3500 year old cypress tree known as “The Senator” was circulated anew after the tree caught fire and collapsed in 2012 (Clark pp.92-93).