Tomorrow, April 15, will mark the ninetieth anniversary of the dedication by President Calvin Coolidge of Arizona’s distinctive state stone into the internal walls of the Washington Monument in 1924. Despite being the last of the 48 to join what Coolidge called the “family” of states, the President knew Arizona would not be the last. In his vision of the future, Arizona, like all of America’s states, carried boundless potential and would reach into vast horizons of great achievement.

“It was a fine conception, this, of placing a stone for every State in the Monument to Washington. Who among us will venture to guess how many more times this ceremony will be performed?” He would venture that guess, “…I think we may almost say the assurance, that before many more years our successors will gather here again and once more survey the wonder of American development, as they dedicate the stone of the 49th State. After that, the story of the States will be written by the finger of destiny on the scroll of a long future. It is not for us to know what that story may be. I hope it can be of duty done to the world, but without aggrandizement, without imperialism…”

“I have thought of today’s ceremony as a sort of home gathering of the States, in honor of the coming of age of the youngest member of the family. It is Arizona’s day, and to Arizona we bring our congratulations, our tributes, our affection and our good wishes for her future…It is to this Arizona of tomorrow, to this greater Southwest which the not distant future will know, as we cannot yet fully conceive it, that we today extend the hand of welcome. We dedicated its stone in this national Monument…yet it is only one of the 48 imperial communities which make up our Nation, in which the people hold the proud distinction of being at once citizens and sovereigns.”

Coolidge identified the significance of this dedication not merely as another occasion to deliver a speech or appeal to mundane platitudes but as an opportunity to consider the importance of each state in our political system, celebrating the principle of local self-governance and the strength each state contributes to the soundness of the whole structure. Coolidge reminds us that an all-encompassing, all-consuming National Government is not an indicator of health and well-being, but rather stems from the failure of that most crucial pillar of local governance. If the people, through their States, abdicate the responsibility to manage their own affairs and make their own decisions, they become suppliant supplicants to Washington, and hasten the collapse of the entire structure.

“This occasion has its important and impressive symbolism. Just as this stone and its associates when joined together make a new and altogether different structure than is represented by each standing alone, so the joining of the States makes a new and different political structure.” Just as each stone had to retain its solidity to sustain the Monument, “so in our Nation each State must remain intact, or the political edifice falls.”

Composed of three petrified logs from the Chalcedony Forest in Holbrook, Arizona, the 2 x 4-foot stone rests at the 320-foot level of the interior wall in the Washington Monument.

As Coolidge stood beside Arizona’s striking contribution to the Monument honoring Washington, he understood that “two policies must always be supported. First, local self-government had to continue persisting not simply as a slogan or motto but “in harmony with the needs of each State. This means that in general the States should not surrender, but retain their sovereignty, and keep control of their own government.” The one-size-fits-all “democracy” enforced from a given Federal agency, office or bureau destroys this powerful role each State possesses. If the States lose control of their own sphere of obligations, it only enables the National Government to assert itself with even more inept and reckless results. Still, Coolidge understood that our system did not succeed with a rejection of all government for libertarianism. As he continues, what he would outline next was as equally indispensable for the future of America’s States as the first policy. Second, local sentiments must be a reflection of a “nation-wide public opinion. Each State must shape its course to conform to the generally accepted sanctions of society and to the needs of the Nation. It must protect the health and provide for the education of its own citizens. The policy is already well recognized in the association of the States for the promotion and adoption of uniform laws.” If the States deviated too far from the moral aims and cultural norms of the country as a whole, it would lead to the disregard and impotence of law everywhere. Even more dangerous, it would furnish another excuse for Washington to assume control in order to bring “security” to the situation: asserting jurisdiction over property it did not lawfully possess, over rights no more permitted to grant than to take away, and over details it could not competently understand.

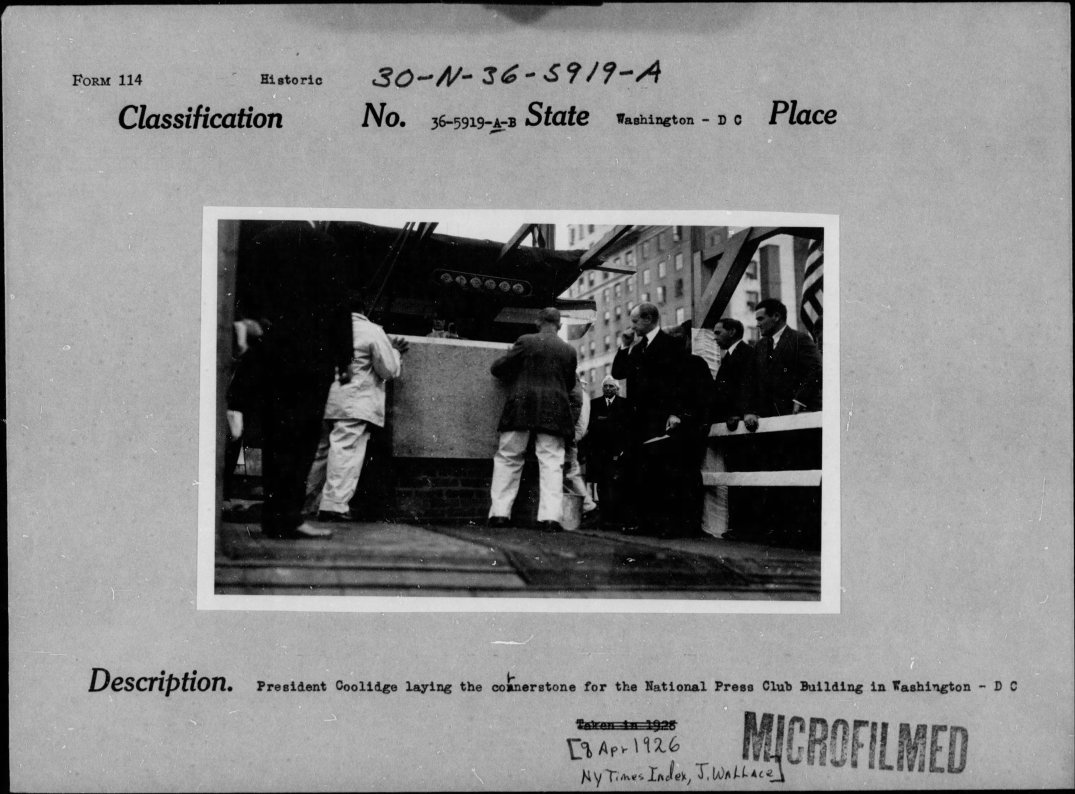

While there would three other states (North Dakota, 1926; New Mexico, 1927; and Idaho, 1928) to join the “family” of State stones during the 1920s, President Coolidge would return only once more to dedicate the 47th state, New Mexico’s contribution, on December 2, 1927. Here is a small snapshot of that occasion.

President Coolidge then drove the point home, “Throughout our whole Nation there is an irresistible urge for the maintenance of the highest possible standards of government and society. Unless this sentiment is heeded and observed by appropriate state action, there is always grave danger of encroachment upon the states by the National Government. But it must always be realized that such encroachment is a hazardous undertaking, and should be adopted only as a last resort. The true course to be followed is the maintenance of the integrity of each state by local laws and social customs, which will place it in comparative harmony with all the others. By such a method, which can only be the result of great effort, constantly exerted, it will be possible to maintain an ‘Indestructible Union of Indestructible States.’ The maintenance of this position rises in importance above the hope of any other benefits, which constant changes would be likely to secure. The Nation can be inviolate only as it insists that Arizona be inviolate.”

We will do well to reflect on this ninetieth anniversary of a great dedication to Arizona and the Monument to our first President. But that is not all. Tomorrow also affords us the occasion to reflect on our responsibilities, the continuous duty we bear to zealously preserve self-government, vigilant States and a limited Washington.