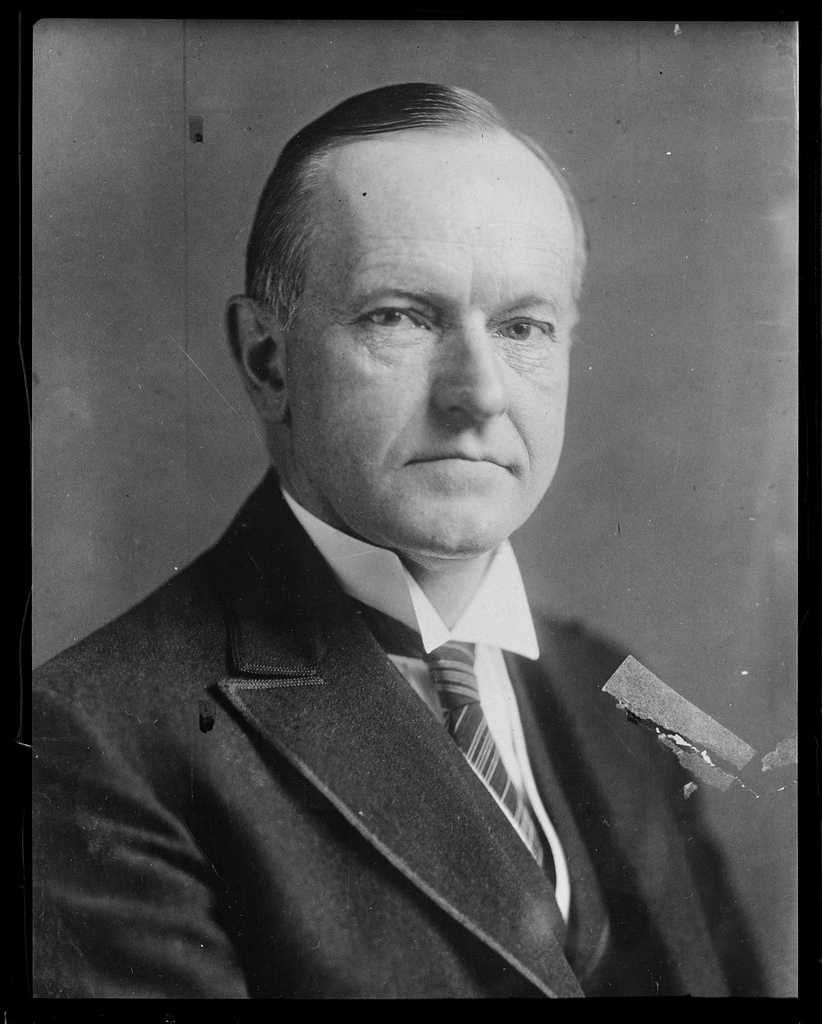

President Coolidge addresses those in the communications field assembled for the Third Radio Conference at the White House, October 8, 1924. On that occasion, he declared, “The Administration, through Secretary Hoover, has from the beginning insisted that no monopoly should be allowed to arise, and that, to prevent it, the control of the channels through the ether should remain as much in the hands of the Government, and therefore of the people, as the control of navigation upon the waters; that while we retain the fundamental rights in the hands of the people to the control of these channels we should maintain the widest degree of freedom in their use” (emphasis added) This, above all other principles, was why Coolidge signed the 1927 Act, as it kept radio free to grow in the hands of the people (as they envisioned it), limiting monopolization without delving into a regulation of content and censorship decisions. In fact, it specifically prohibited self-appointed censors from holding any legal authority under the Act (sections 18-19). Thanks to Coolidge, the commercial potential of radio was unleashed resulting not only in the benefits of economic opportunity for millions of people but also the spread of knowledge, civic participation and educational blessings as well. His faith in the judgment and ability of the American people to do best when they retain maximum liberty pervades his contributions to radio.

It was on this day in 1927 that President Coolidge signed the Radio Act which brought both continuity and order from the disarray of early radio communications. From the chaos over frequencies and content to oversight and licensing, the ground rules Coolidge established for the future of radio remain sound even with the passing of the years and the march of technology.

Coolidge dealt in essential principles ensuring that radio remained free to adapt flexibly and grow into a powerful medium for much good without stifling creativity or discouraging the opportunity for everyone to participate.

The legislation created a Federal Radio Commission, comprised of five members appointed by President Coolidge at the selection of Secretary Hoover. It was a crucial distinction for the future that this Commission remain under the authority of the Commerce Department. The bill provided that it would work as a quasi-independent body for 1 year and then return to the oversight of the Commerce Department and Coolidge’s Executive Branch. Thwarting yet another growth of government bureaucracy was essential to Cal. When the law was replaced under F.D.R. in 1934, the two basic changes to emerge by 1949 — since the essence of the Radio Act rested on so sound a foundation — were: (1) ensuring the permanent bureaucracy of the Commission, separated from elective accountability, replacing Coolidge’s merit-based practitioners in the radio field with professional politicians and (2) introducing by 1949 (under Truman) what became known as the “Fairness Doctrine” that exceeded the provisions of Section 18 of the 1927 Act by requiring all candidates be given equivalent airtime regardless of the programming format or broadcasting constraints. It was sold in terms of the public good but as those who experienced it quickly learned, it neither protected freedom of speech nor the public.

Coolidge commended Hoover for selecting men not for their party or political connections but for their practical experience in radio, electronics and broadcasting. Coolidge also approved of the safeguards in keeping a short leash on the Commission, helping to pull it back from independence outside the Executive Branch, authorized under the Constitution. Coolidge further backed both the commercial future of radio (by placing it under the Commerce Department’s administration) but also the maximum involvement of as many people as possible, rather than a few large conglomerates and monopolistic tycoons. He saw the future blessings of radio in the direction of order with participation and liberty with responsibility. In this way, he confirmed the future of freedom of speech in radio as well as ensuring that the medium best functioned not for the job security of a political class but as the expression of a free people engaged in their interests, work, commerce with and service to others.

Coolidge explained his mind on the danger of an unelectable, independent bureaucratization of radio this way on April 27, 1926, “I think it would be a wise policy to keep the supervision over radio or any other regulatory legislation under some of the present established departments. Otherwise, the setting up of an independent commission gives them entire jurisdiction without any control on the part of the Executive or anywhere else. That is the very essence, of course, of bureaucracy, an independent commission that is responsible to nobody and has powers to regulate and control the affairs of the people of the country. I think we ought to keep as far away from that as we can, wherever it is possible.”

Subsequent experience has certainly vindicated Coolidge’s principles on the matter.

For some excellent further reading, start with these:

Wallace, Jerry L. Calvin Coolidge: Our First Radio President. Plymouth Notch: Calvin Coolidge Memorial Foundation, 2008.

Banning, William Peck. Commercial Broadcasting Pioneer: The WEAF Experiment 1922-1926. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1946.

Barnouw, Erik. A Tower in Babel: A History of Broadcasting in the United States, vol. 1 – to 1933. New York: Oxford University Press, 1966.

Godfrey, Donald G. and Frederic A. Leigh, eds. Historical Dictionary of American Radio. Westport: Greenwood Press, 1998.

Smulyan, Susan. Selling Radio: The Commercialization of American Broadcasting, 1920-1934. Washington: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1994.