“Friends and Fellow Citizens:

“It is one of the glories of our country that we all have the privilege of being Americans. Some of us were born here of an ancestry that has lived here for generations. Others of us were born abroad and brought here at a tender age, or have come to these shores as a result of mature choice. But when once our feet have touched this soil, when once we have made this land our home, wherever our place of birth, whatever our race, we are all blended in one common country. All artificial distinctions of lineage and rank are cast aside. We all rejoice in the title of Americans. But this is not done by discarding the teachings and beliefs or the character which have contributed to the strength and progress of the peoples from which our various strains derived their origin, but rather from the acceptance of all their good qualities and their adaptation to the requirements of our institutions. None of those who come here are required to leave any good qualities behind, but they are rather required to strengthen and fortify them and supplement them with such additional good qualities as they find among us.

“While it is eminently proper for us to glory in our origin and to cherish with pride the contributions which our race has made to the common progress of humanity, we can not put too much emphasis on the fact that in this country we are all bound together in a common destiny. We must all be united as one people. This principle works both ways. As we do not recognize any inferior races, so we do not recognize any superior races. We all stand on an equality of rights and of opportunity, each deriving just honor from their own worth and accomplishments. It is not, then, for the purpose of setting one people above another that we assemble here to-day to do reverence to the memory of a great son of Sweden, but rather to glory in the name of John Ericsson and his race as a preeminent example of the superb contribution which has been made by many different nationalities to the cause of our country. We honor him most of all because we can truly say he was a great American.

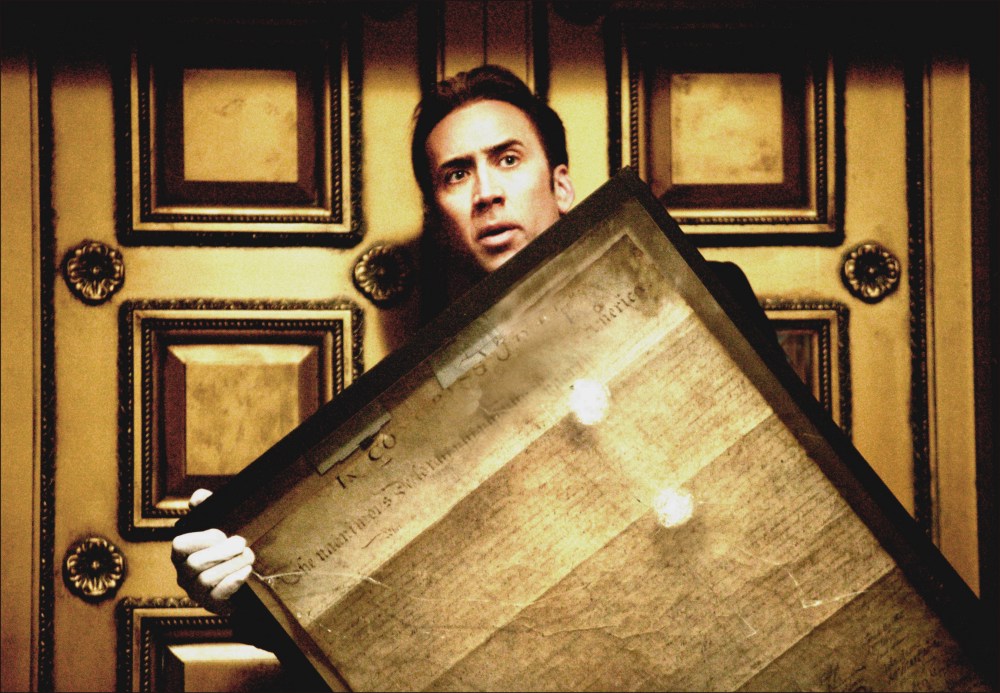

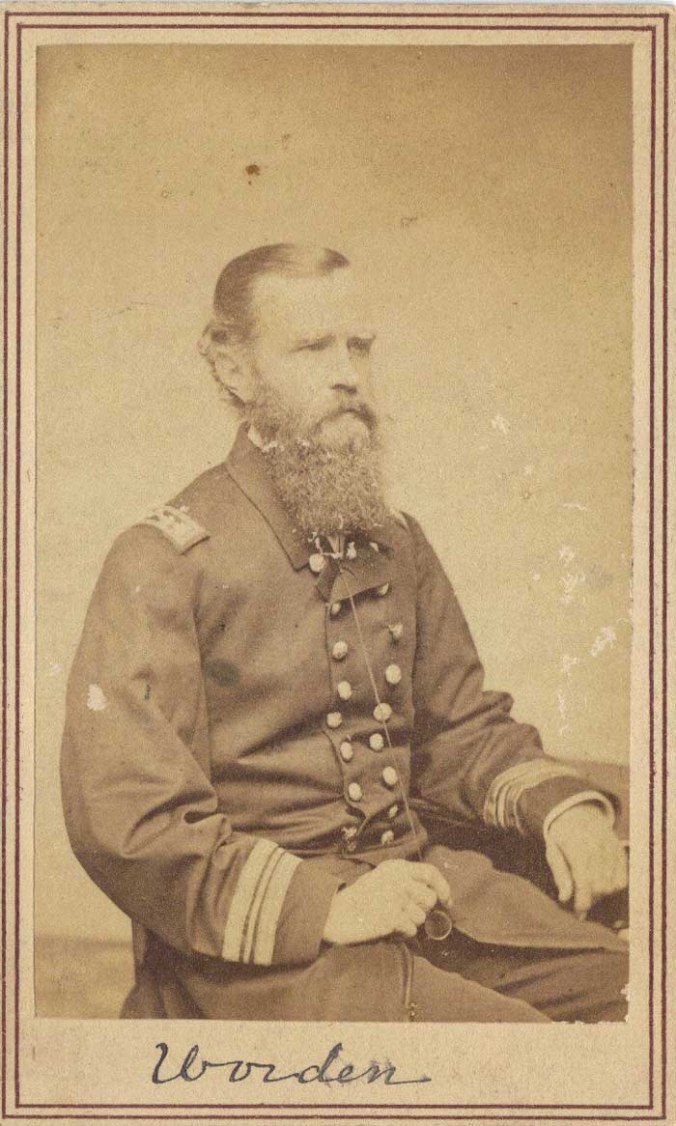

John Ericsson, 1862

“Great men are the product of a great people. They are the result of many generations of effort, toil, and discipline. They do not stand by themselves; they are more than an individual. They are the incarnation of the spirit of a people. We should fail in our understanding of Ericsson unless we first understand the Swedish people both as they have developed in the land of their origin and as they have matured in the land of their adoption.”

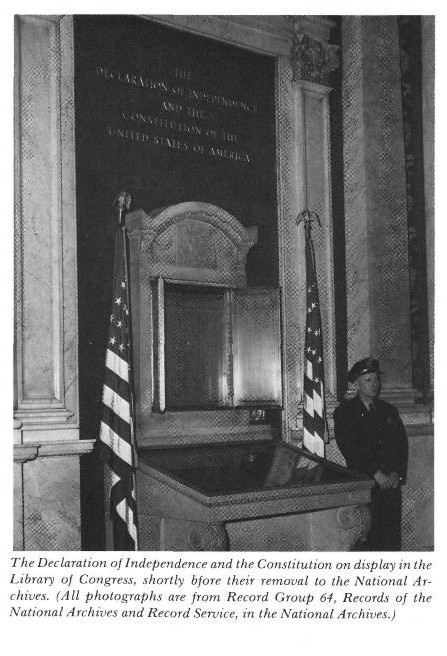

Coolidge proceeded to recount precisely that development of the Swedish people. From the rugged terrain under the Arctic these hardy people have demonstrated “independence, courage and resourcefulness” since ancient time, taking to the seas, defending greater and greater religious freedom and leaving a fixed imprint on the growth and success of America. Establishing a colony here in 1638, they “laid the basis for a religious structure, built the first flour mills, the first ships, the first brickyards, and made the first roads, while they introduced horticulture and scientific forestry into the Delaware region.”

“Landing of the Swedes” by Stanley M. Arthurs, depicting the first contact in 1638 between Swedish settlers and Delaware Indians along the Christina River in what is now Wilmington.

They not only cleared and cultivated the forests and prairies but they built churches and charities, established schools and businesses. Despite being “few in numbers…they supported the Colonial cause and it has been said that King Gustavus III, writing to a friend, declared, ‘If I were not King I would proceed to America and offer my sword on behalf of the brave Colonies.’ “ John Mortenson was among the Signers of the Declaration and John Hanson among those to hold the office of “President of the United States in Congress Assembled.” It would be Sweden to become the “first European power which voluntarily and without solicitation tendered its friendship to the young Republic” in 1783. But also, with the removal in 1843 of restrictions in their native land, the large number of Swedish immigrants began their move to America and greater liberty.

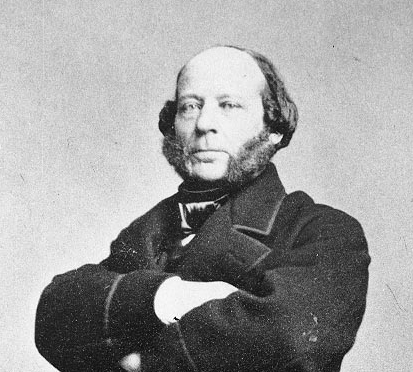

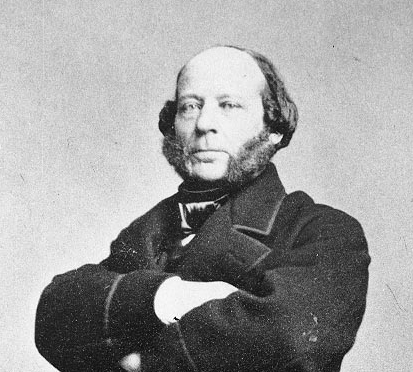

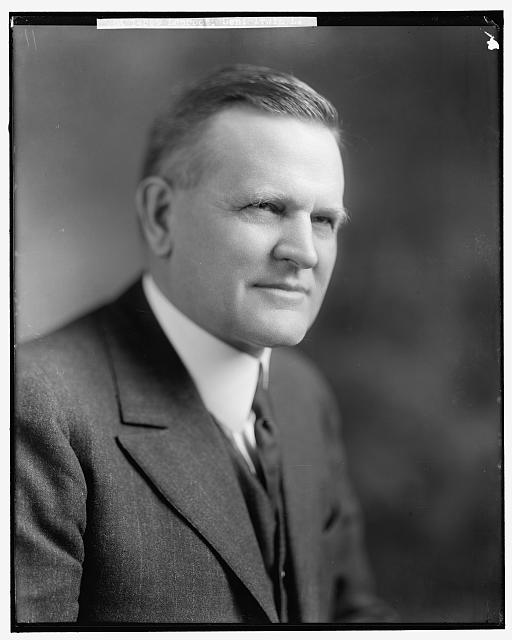

“As these Americans of Swedish blood have increased in numbers and taken up the duties of citizenship, they have been prominent in all ranks of public life.” They have served with equal distinction not only as governors and mayors, generals and admirals but also painters and musicians. Yet, Coolidge took the occasion to name one of many who exemplified that “old Norse spirit, a true American,” Irvine L. Lenroot of Wisconsin. While it is ironic that Senator Lenroot was supposed to be the Vice Presidential choice alongside candidate Harding at the 1920 Republican convention, the rank and file delegates had very different ideas of who was best qualified. Of course, we know their choice fell enthusiastically and spontaneously upon Calvin Coolidge. It is noteworthy that now as President in his own right, Coolidge exacts no political gloating or grandstanding. Instead, Mr. Coolidge recognizes his earliest national rival with respect and selfless praise, making his point of American exceptionalism even stronger.

Irvine Luther Lenroot, Senator from Wisconsin, 1918-1927, was the man who “might have been the thirtieth president of the United States.” Coolidge, despite being decisively chosen by the delegates over Lenroot, exemplified dignity and class as his words at this dedication of Ericsson’s memorial illustrate.

“…Such is the background and greatness of the Swedish people in the country of their origin and in America that gave to the world John Ericsson. They have been characterized by that courage which is the foundation of industry and thrift, that endurance which is the foundation of military achievement, that devotion to the home which is the foundation of patriotism, and that reverence for religion which is the foundation of moral power. They are representative of the process which has been going on for centuries in many quartered of the globe to develop a strain of pioneers ready to make their contribution to the enlightened civilization of America.” The strength of America is not in its multicultural diversity, the non-essentials that keep us divided, but in its ability to attract and assimilate so many good qualities around a shared identity, a common set of principles, creating a new union of peoples called Americans.

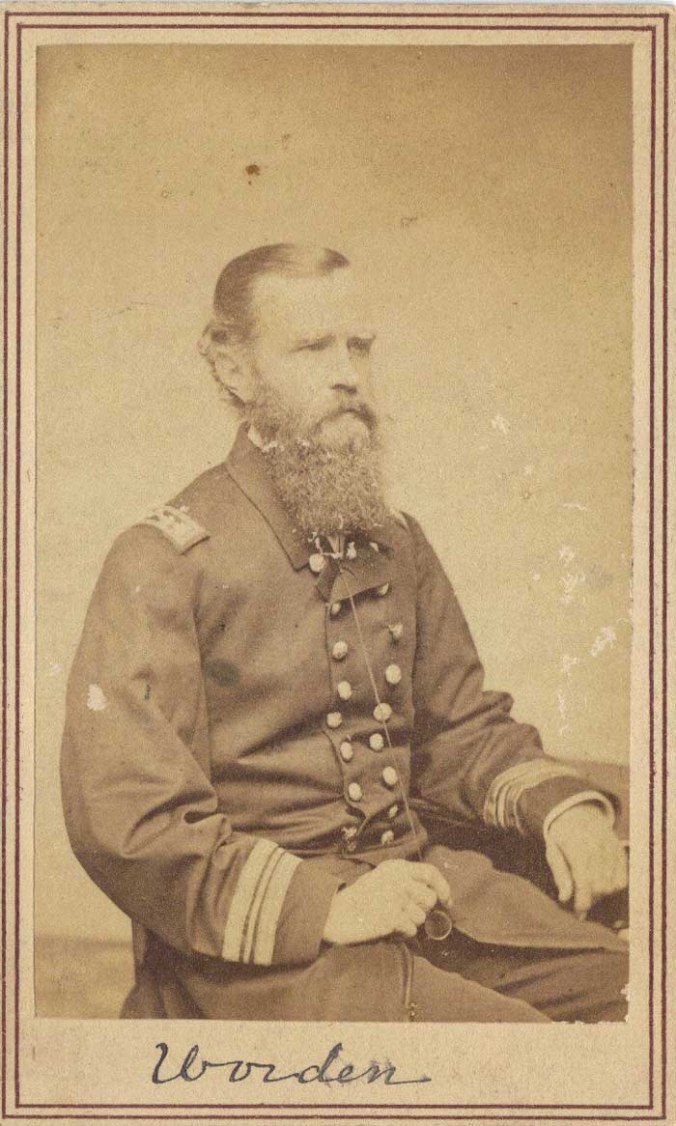

John Ericsson validates that long-proven tradition. “The life of this great man is the classic story of the immigrant,” Coolidge reminds us, “the early struggle with adversity, the home in a new country, the final success.” Ericsson’s focus and fascination with engineering made possible the accomplishment of the Princeton, “which was the first man-of-war equipped with a screw propeller and with machinery below the water line out of reach of shot.” Ericsson did not stop there, however. His next great achievement “steamed into Hampton Roads late after dark on the day of March 8, 1862. It arrived none too soon, for that morning the Confederate ironclad Virginia, reconstructed from the Merrimac, began a work of destruction among the 16 Federal vessels, carrying 298 guns, located at that point.” The Cumberland had been pummeled to submission, the Congress was grounded and aflame, and the Roanoke and Minnesota were “damaged and run ashore.” Europe watched and stood ready to recognize the Confederacy with the next swift victory. Yet, the unprecedented success of the Merrimac would be matched with an equally “new and extraordinary naval innovation” in the Monitor. As Admiral Luce would observe years later, it was the Monitor which “exhibited in a singular manner the old Norse element in the American Navy,” since it was Ericsson “who built her,” Dahlgren “who armed her,” and Worden “who fought her.”

The USS Monitor battles the CSS Virginia, formerly the USS Merrimac, Hampton Roads, March 8, 1862. Depiction by J. O. Davidson.

“After a battle lasting four hours in which the Monitor suffered no material damage, except for one shell which hit the observation opening in the pilot house, temporarily blinding Lieutenant Worden, the commanding officer, the Merrimac, later reported to have been badly crippled, withdrew, never to venture out again to meet her conqueror. The old spirit of the Vikings, becoming American, had again triumphed in a victory no less decisive of future events than when it had hovered over the banner of William the Conqueror…That engagement revealed that in the future all wooden navies would be of little avail…The great genius of Ericsson had brought about a new era in naval construction…Great as were these achievements, they are scarcely greater than those which marked the engineering and inventive abilities of this great man, which were to benefit the industry, commerce, and transportation of the country. He was a lover of peace, not war. He was devoted to justice and freedom and was moved by an abiding love of America, of which he had become a citizen in 1848.”

Admiral John A. Dahlgren, beside one of his inventions, a 50-pounder Dahlgren rifled gun. His “soda bottle” design ensured greater safety and accuracy in artillery operation. The Monitor had two such guns.

Lieutenant John L. Worden, commander of the Monitor in that historic match between steam-powered ironclads, March 8-9, 1862.

“Ericsson continued his labors in his profession with great diligence, even into his eighty-sixth year, when he passed away at his home in New York City on the 8th of March, 1889, the anniversary of the arrival of Monitor in Hampton Roads. At the request of the Royal United Kingdoms of Sweden and Norway, all that was mortal of the great engineer was restored to his native land during the following year.” In debt to what we owed to Sweden for what Admiral Schley called “the gift of Ericsson,” his body was returned to “his native country.” “Crowned with honor” by not only the land in which he was born but also America, “the land of his adoption, he sleeps among the mountains he had loved so well as a boy. But his memory abides here.”

It was this occasion that rejoined both America and Sweden in the dedication of “another memorial to the memory of this illustrious man.” President Coolidge would stand with Crown Prince Gustaf Adolf and Crown Princess Louise “to be present…and join with us in paying tribute to a patriot who belongs to two countries. It is significant that as Ericsson when he was a young soldier had the friendship and favor of the Crown Prince of that day, so his memory has the marked honor of the Crown Prince of to-day.”

“As the ceaseless throng of our citizens of various races shall come and go,” Coolidge concluded, “as they enter and leave our Capital City in the years to come, as they look upon their monument and upon his and recall that though he and they differed in blood and race they were yet bound together by the tie that surpasses race and blood in the communion of a common spirit, and as they pause and contemplate that communion, may they not fail to say in their hearts, ‘Of such is the greatness of America.’ “

The John Ericsson Memorial, sculpted by James Earle Fraser from pink Milford granite. Fraser would create some of the most iconic images of modern time, including the Indian head on the Buffalo nickel, the bronze of General Patton at West Point, the Franklin Memorial in Philadelphia and the Contemplation of Justice atop the Supreme Court Building in Washington.