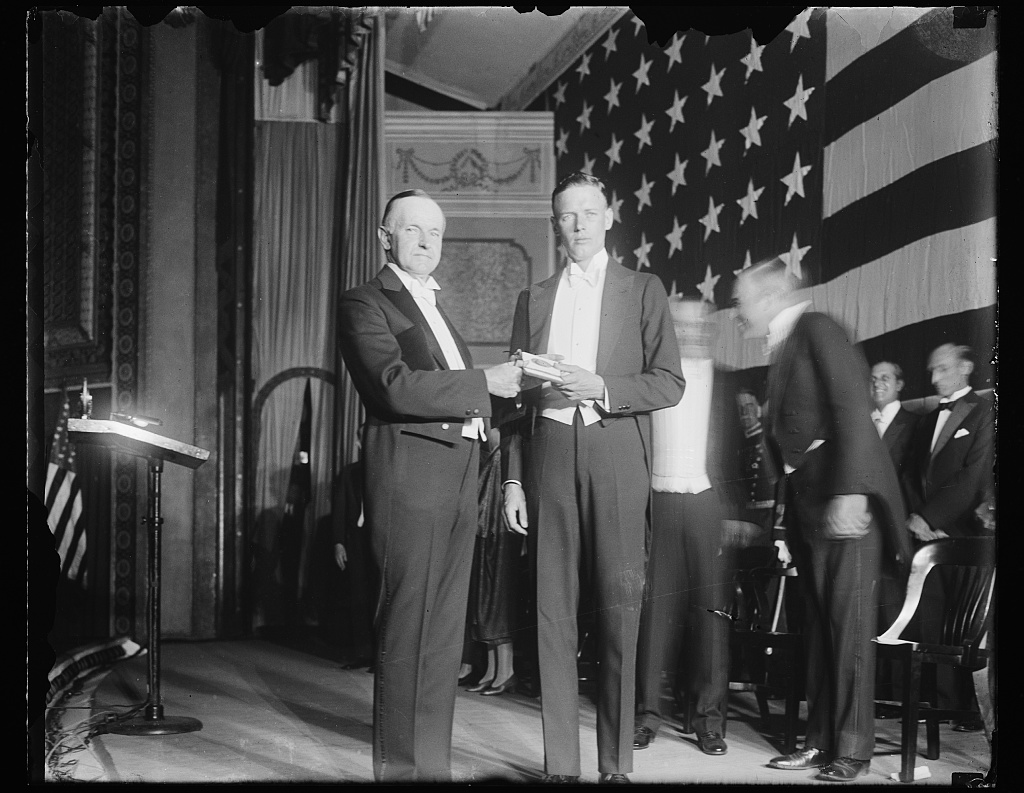

In observance of our 400th post here, together with the anniversary this week of Calvin Coolidge’s 1928 Address before the 400 delegates gathered together from the American Federation of Arts and the American Association of Museums, we will offer some especially cogent highlights from the speech. These excerpts illustrate what Coolidge thought of art and that what gave it value and meaning resides in its revelation of reality, truth, and beauty. Here are some of my favorite gems from a little known, oft overlooked but insightful message from President Calvin Coolidge:

“While we have been devoted to the development of our material resources, as a nation ought to be which heeds the admonition to be diligent at business, we have not been neglectful of the higher things of life. In fact, I believe it can be demonstrated that the intellectual and moral awakening which characterized our people in their early experiences was the fore-runner and foundation of the remarkable era of development in which we now live. But in the midst of all the swift-moving events, we have an increasing need for inspiration. Men and women become conscious that they must seek for satisfaction in something more than worldly success. They are moved with a desire to rise above themselves. It is but natural, therefore, that we should turn to the field of art…

“…[I]n a wider sense, the arts include all those manifestations of beauty created by man which broaden and enrich life. It is an attempt to transfer to others the highest and best thoughts which the race has experienced. The self-expression which it makes possible rises into the realm of the divine.” Not everything is art or artistic, Coolidge knew, and though beauty may be in the eye of the beholder it is real art to conceive and design something that broadens and enriches life, that serves as a vessel to bequeath the “highest and best thoughts” mankind has known. That inspiring standard is simply missing from much of what is now sponsored as great, modern art.

A night snapshot of “White City” with its famous tower. The tower was a landmark visible up to fifteen miles away. In his mention of this turn-of-the-century amusement park, Coolidge lauds one very specific quality of that site: the inspiration it fostered in those “who had the good fortune to visit it” of a desire to beautify surroundings nation-wide. Coolidge was keenly aware that circumstances had not always been peaceful in and around White City and many had never been there — yet, as with so many things, Coolidge appealed to higher ideals, to what could and should be, to the potential each individual possesses instead of an acceptance of what is now.

Emerging out of the struggle to survive during the first half of the nineteenth century and then to build the country, America turned to the mastery of architecture. Coolidge recounts the great names whose mark remains in the lines and form of Henry H. Richardson’s work, Trinity Church in Boston, the labors of Stanford White and Augustus Saint-Gaudens, the resplendence of the White City in south Chicago, the ornate grandeur of the murals at the Library of Congress and the majestic redesign of Washington’s public buildings making it, as even Coolidge envisioned, “the most beautiful capital in the world.”

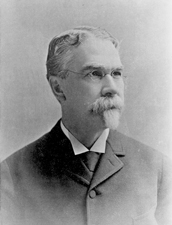

Born in Louisiana, Henry H. Richardson would become a legendary designer of many a Northern landmark, ushering in his own Romanesque style and standing as one of the foremost influences on American architectural designs.

It was not only in creating great art, however, that service to nobler principles is rendered, it is also in the preservation and availability afforded by museums that people can find “the development of an artistic sense” as well as “the love of the beautiful.” Coolidge ushers us to the expansive outdoors in full appreciation for the unsurpassed natural canvas within our reach. “Encouragement and aid have been given in the establishment of new museums, particularly those of the small-community type. To furnish facilities for nature study and to enhance the enjoyment of life out of doors, museums have been started in our National and State parks. Whatever may be done to increase museum facilities and to render their collections of more use to mankind as a most valuable service…deserves every encouragement.”

The profile of Stanford White’s Madison Square Garden stand against the skyline, left of the Clock Tower (at right), in this photograph from 1923. It was the second tallest building in New York City in its time.

Here is the very controversial statue of Diana the huntress standing at the pinnacle of the Madison Square Gardens’ tower. It was designed by none other than the great Augustus Saint-Gaudens. Concerns over the modesty (or lack thereof) of the design caused quite an uproar for many years. A cloth was actually manufactured to cover the statue but it soon blew away. Interestingly, Diana now resides with the Philadelphia Museum of Art, given in 1932 by the owners of the old Garden location, New York Life Insurance Company.

For Coolidge, the importance of art was not merely its aesthetic qualities but its practical role in improving our lives and the places around us. It meant getting out of the stifling office and back to the woods, the hills and plains, steams and lakes of our country. It meant getting back outside, reconnecting with reality and regaining the unique perspective time in nature can alone provide. “If clothes make the man – and certainly good dress gives one a sense of self-respect and poise – how much more is it true that clean, beautiful surroundings lend a moral tone to a community.” Consequently, without a single government program or legislative package, the “squalor of the slums of our big cities and…the oppressive ugliness of some of the small towns” began going away during the 1920s, a point Coolidge praised. Economic growth encouraged by Coolidge’s tax and budgetary cutting helped, of course, but so did his repeated admonitions to take stock of spiritual things, cultivating our moral power above and beyond our material success. After all, it was the strength of the soul and the resilience of the family that made the home stand, not the steel and concrete or bricks and mortar of a building, however impressive on the outside.

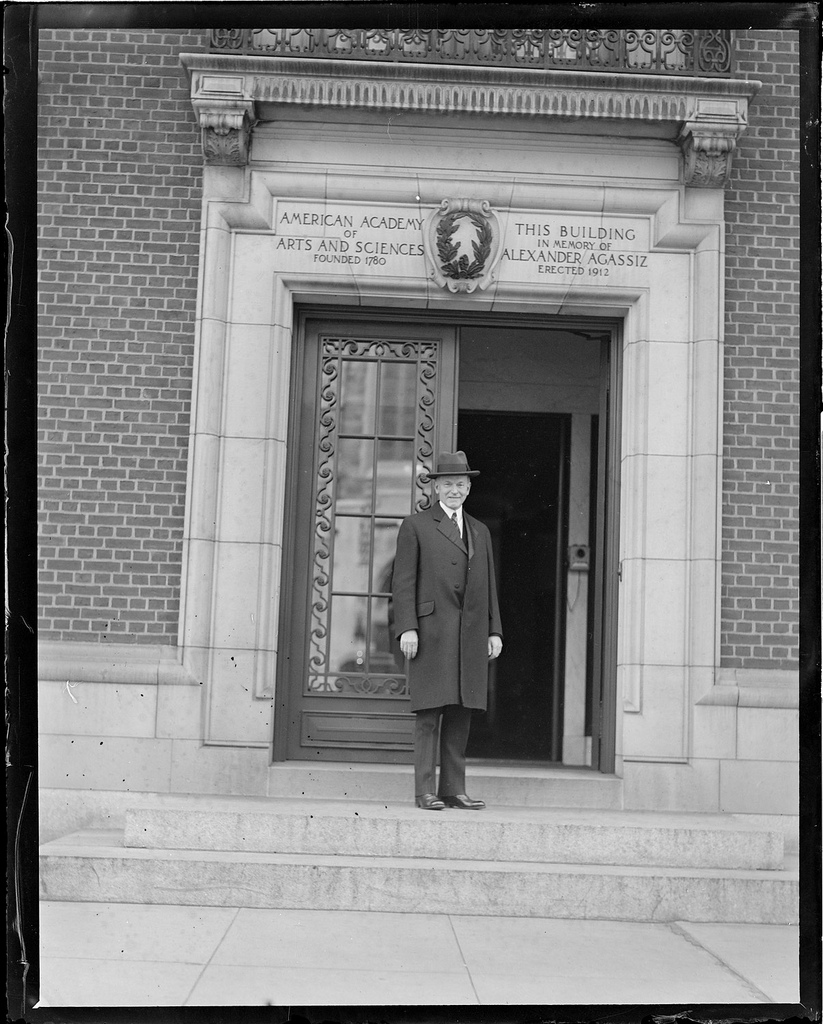

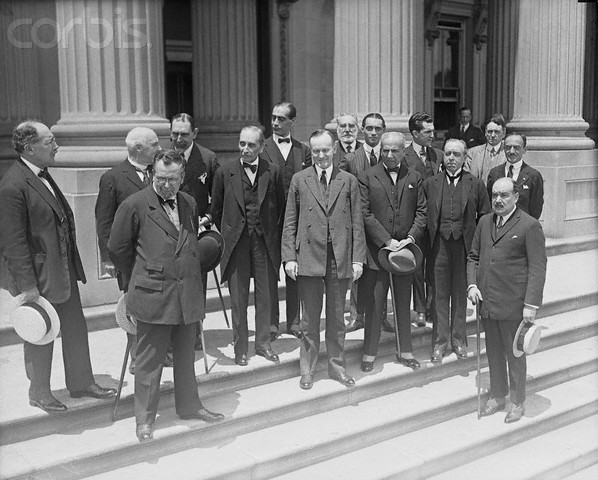

Envisioned by Mcmillan and his commission to convey the dignity and grandeur of our Republic, as embodied in its traditions and institutions, the “Federal Triangle” project had been advocated for many years before the 1920s. It would be largely through the sacrifice and persistence of Treasury Secretary Andrew Mellon (including no insignificant part by Coolidge himself) that it would finally see completion in 1938.

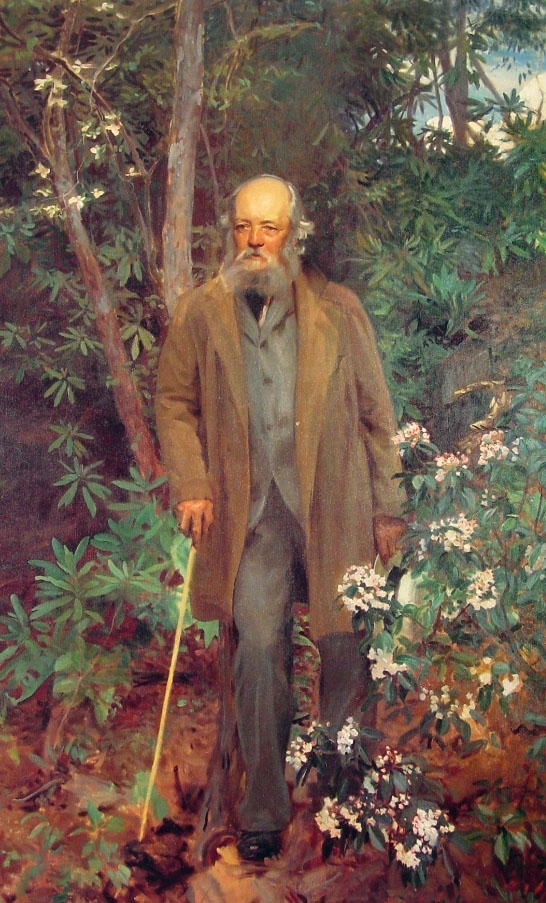

The incomparable Frederick L. Olmstead left a profound mark on landscape architecture in America, from New York’s Central Park to the design of the Capitol grounds in Washington and, through sons John and Frederick Jr., from the Chicago World’s Fair to the Bok Tower and Gardens in Lake Wales, Florida. He, more than any other designer of his time, underscored the enduring importance of what Coolidge emphasizes in this speech: renewing again our appreciation for and connection to America’s natural beauty.

Art was something more to him than a mere abstraction, it was a reflection of the soul, a diagnosis of the spirit, nationally and individually. This is why caring about genuine beauty and truth had a larger significance than the artifacts in a museum gallery. “It is especially the practical side of art that requires more emphasis. We need to put more effort into translating art into the daily life of the people. If we could surround ourselves with forms of beauty, the evil things of life would tend to disappear and our moral standards would be raised. Through our contact with the beautiful we see more of the truth and are brought into closer harmony with the infinite.”