“Death and life are in the power of the tongue; and they that love it shall eat the fruit of it” — Proverbs 18:21

“A word fitly spoken is like apples of gold in fittings of silver” — Proverbs 25:11

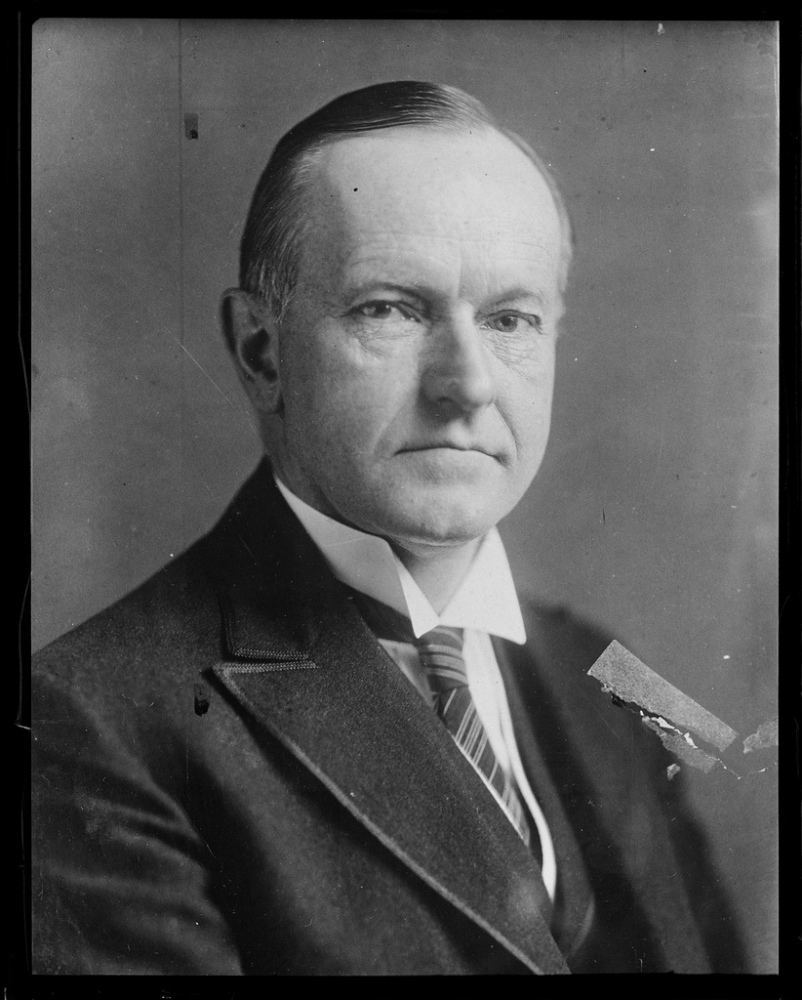

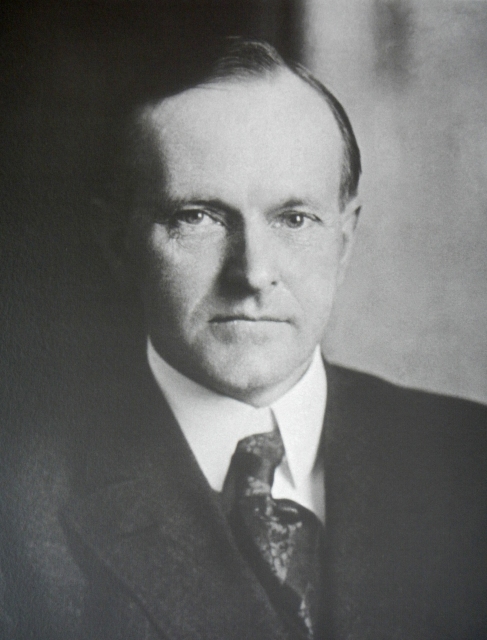

Few, especially in public life, have respected the truth of these maxims than Calvin Coolidge. He understood the power of the spoken word. It carries the ability to inspire one to greater heights of goodness and nobility or to destroy with malice and hatred. It can build up the soul or crush the spirit. It carries a potency that cannot be entirely harnessed or contained once uttered and thus dare not be exercised flippantly or with casual disregard for the responsibilities which fall to the speaker, especially as the President of the United States of America.

Coolidge wielded this power effectively during his Presidency by deploying the spoken word sparingly, giving what he would say maximum effect upon the listener. Coolidge knew the speaker can control the timing of what is said while the damage done to credibility by spiteful and vindictive rhetoric cannot be undone. If the President gave legitimacy to what is petty, hateful and divisive, however culturally or politically influential those forces may be, it would be no less an abdication of duty than the Boston police abandoning their posts to the lawless and violent. It would bring impugn not only the trust placed in our leaders but upon what America is and what it has done, as Coolidge noted in his Inaugural Address in 1925. This is why he so carefully withheld his words and refrained from being the first to intervene with “comment” upon every area of life. Experience taught him that more harm came when a President indulges the desire to be “quick to speak” and “slow to hear” without a fair hearing of all the facts thereby taking sides against the fairness and decency of Americans. This is why his silence and refrained involvement, so often mistaken for insensitivity, disinterest or rudeness, were actually measured with a sincere and heartfelt regard for the situation and what was in the best interest of everyone directly concerned. His respect for people gave him pause. After all, Coolidge understood what too many current politicians find to be an inconvenient, confining truth: Freedom is a zero-sum game. Every action taken by the President removes a commensurate ability from individuals to so act for oneself.

With a word, Presidents can exacerbate strife and division or heal and comfort. To have used the Presidential platform and denounced the Klan, as the Democrat candidate Mr. Davis urged in 1924, would have validated an utterly illegitimate organization with enough importance to warrant a sitting President’s attention. The Klan, despite how politically powerful they were, simply did not merit a moment of official recognition. Instead, he went to Howard University and spoke of the genuinely phenomenal advancement of black Americans since emancipation. To a Mr. Gardner, who wrote protesting the participation of black candidates that election year, Coolidge replied,

“Our Constitution guarantees equal rights to all our citizens, without discrimination on account of race or color. It is the source of your rights and my rights. I propose to regard it, and administer it, as the source of the rights of all the people, whatever their belief or race. A colored man is precisely as much entitled to submit his candidacy in a party primary, as is any other citizen. The decision must be made by the constituents to whom he offers himself, and by nobody else. You have suggested that in some fashion I should bring influence to bear to prevent the possibility of a colored man being nominated for Congress. In reply, I quote my great predecessor, Theodore Roosevelt: ‘I cannot consent to take the position that the door of hope–the door of opportunity–is to be shut upon any man, no matter how worthy, purely upon the grounds of race or color.’ ”

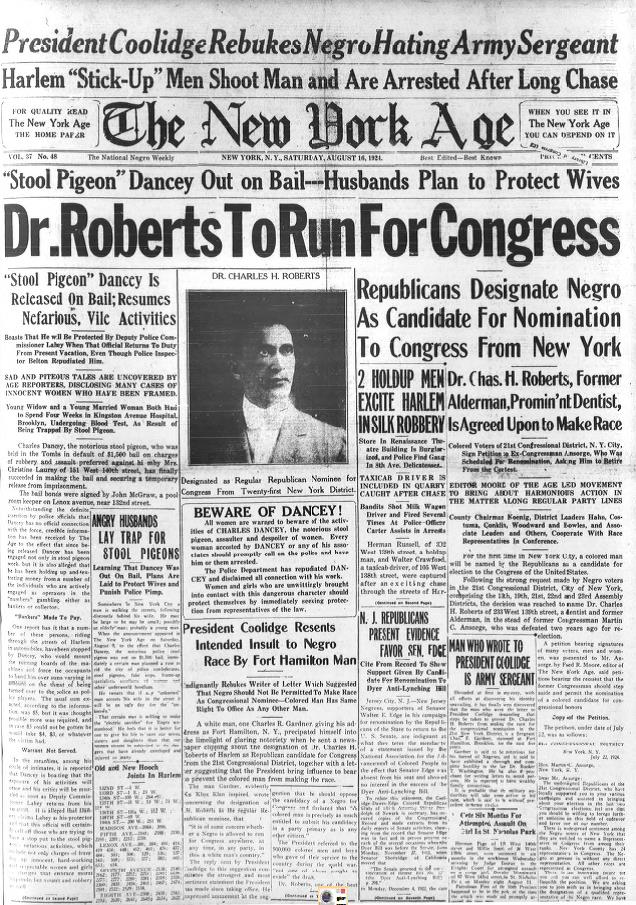

August 16, 1924 edition of The New York Age. Coolidge’s emphatic endorsement of Harlem’s candidate, Dr. Roberts, further strengthened the credibility and trust between Cal and black Americans. W. E. B. DuBois estimated that 1 million blacks voted for Coolidge that fall.

He went to the Holy Name Society and declared, “He who gives license to his tongue only discloses the contents of his own mind. By the excess of his words he proclaims his lack of discipline. By his very violence he shows his weakness.” He went to Omaha, two years after Klan-inspired riots shook the city, and Coolidge spoke before the American Legion on October 6, 1925, saying,

“If we are to have that harmony and tranquility, that union of spirit which is the foundation of real national genius and national progress, we must all realize that there are true Americans who did not happen to be born in our section of the country, who do not attend our place of religious worship, who are not of our racial stock, or who are not proficient in our language. If we are to create on this continent a free Republic and an enlightened civilization that will be capable of reflecting the true greatness and glory of mankind, it will be necessary to regard these differences as accidental and unessential. We shall have to look beyond the outward manifestations of race and creed. Divine Providence has not bestowed upon any race a monopoly of patriotism and character.”

He went to the Congress annually over the course of nearly six years to devote a portion of each Message to the circumstances of what then were 12 million “colored” Americans. Offering his set of proposals for Congress to act upon, he recognized “that these difficulties are to a large extent local problems which must be worked out by the mutual forbearance and human kindness of each community. Such a method gives much more promise of a real remedy than outside interference.” He would confront discrimination firmly and bigotry honestly but he would not strip an individual of his or her freedom in order to pursue the impossible: perfect equality through government-directed vengeance.

In what the coming years would reveal was the last desperate gasp of “respectable” Klan retrenchment, the KKK took advantage of Coolidge’s absence from Washington to follow the debacle that was the 1924 Democrat Convention to march down Pennsylvania Avenue, August 8, 1925. Coolidge would help deliver the decline and demise of the Klan’s membership and influence in the years ahead. They would never again be the nationally regarded organization it had been under President Wilson.

He could have opined the injustice of it all, decried the unfairness of “the system” and demanded sweeping legislation to “fix” it. Because he did not hardly makes him a do-nothing enabler, he was appealing to higher ideals than perpetual victimhood. Ideals that constructively edify and encourage everyone to rise above the typical to strive for the exceptional, opportunities at self-betterment and self-sufficiency only possible when individual freedom is honored. It seems that bad laws simply do not exist in the eyes of this current regime. As with any authoritarian, any action is justified to meet the situation. The President behaves as it there is no virtue in refrained action, withholding the use of power to take stock of what collateral damage is being done. In actuality, the array of unintended and intended consequences meted out to political enemies in order to settle scores and correct “inequities” in America’s traditions and institutions is the exact opposite of wisdom or justice. Coolidge reminds us that there are situations when the best use of power is not to parade it, when the wisest means of diffusing conflict is not to advertise it and the surest solutions rest not in Executive word or deed but in the renewed commitment to the ideals on which America began. These ideals find expression not merely in great parchments and speeches but in the lives of a people free to govern themselves.

In the series that will follow on race and Presidential power, we are going to examine Coolidge’s record on race, reappraising what he did do when it came to differences between Americans, how he addressed discrimination and segregation, how he fought to end lynching, how he worked to build up not tear down with the power of the spoken word and acted, usually behind the scenes, to handle requests and calm tensions all without sweeping civil rights legislation or grandiose executive might. His record on race, as with most of Coolidge’s accomplishments, is underrated not because it was uneventful or he did nothing about it but because his record under-promised but over-delivered. In a very real way, Coolidge’s approach to race relations achieved more than the boldness of TR, the retrenchment of Wilson or the flashy promises and empty results of FDR and LBJ. We will explore how in the coming days.

“The words of the President have an enormous weight and ought not to be used indiscriminately. It would be exceedingly easy to set the country all by the ears and foment hatreds and jealousies, which, by destroying faith and confidence, would help nobody and harm everybody. The end would be the destruction of all progress” — Calvin Coolidge, The Autobiography, p.186.