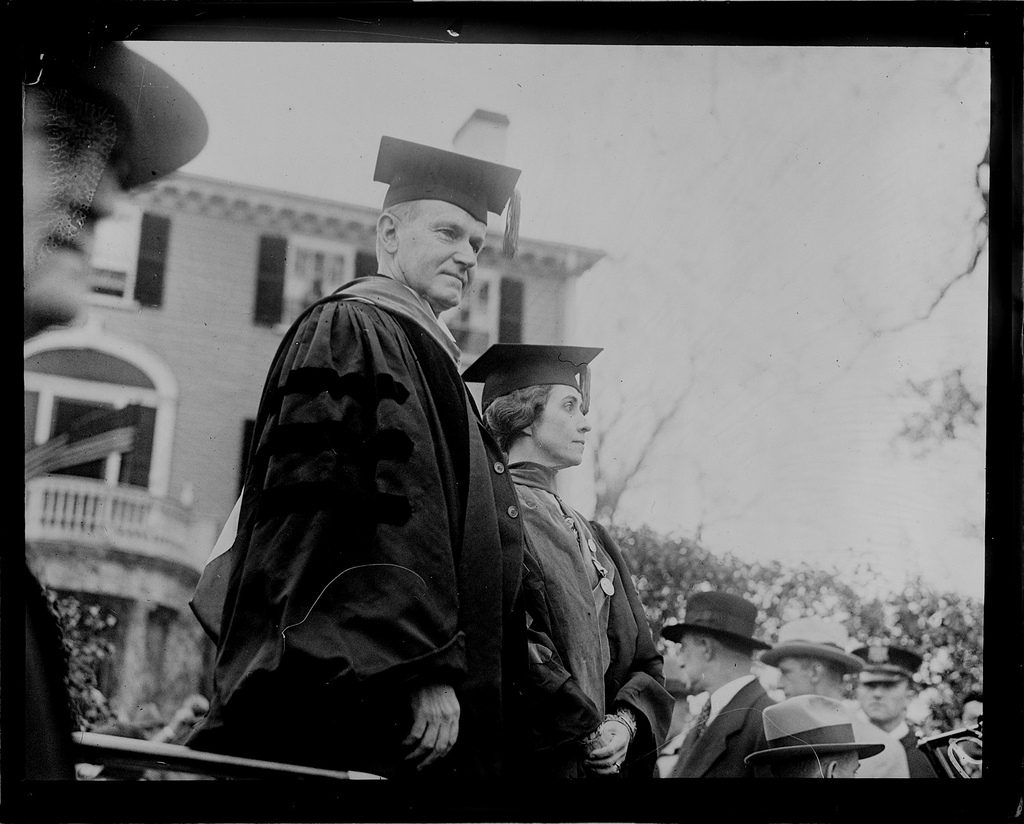

Surveying the immensely strong faculty of Amherst during the time Calvin Coolidge came into contact with the school, Claude M. Fuess, in his book on Amherst, turns to Charles Edward Garman, the professor of philosophy from 1882-1907. It was of Garman’s courses Coolidge would later observe, “all the other studies ‘were in the nature of a preparation’ ” and though Garman’s “actual career at Amherst covered less than a quarter of a century,” he “left behind him an influence such as almost no other college teacher in the United States has exerted.” Graduating from Amherst with the Class of 1872, ironically the year Coolidge was born, Garman went to Yale but his desire to teach brought him back to his alma mater by 1880 through the capable leadership of President Seelye. By 1882, Professor Garman had taken up his signature course in philosophy. Using no textbooks, he had a masterful grasp of dialectics and used it to great effect. “He tried to compel his students to think for themselves, to weigh evidence, to accept nothing on authority, and to follow the truth no matter where it led. He would permit them to build up one after one erroneous systems of belief — would, in fact, assist them in doing so; and then, by questioning, often by fierce discussion, he would destroy the heresy which they had come to regard as infallible. It is characteristic of his modernity that he used a wealth of illustrations from science…he compared public opinion to a cake of ice, which yields to slow pressure but cracks under a sharp blow.”

“…His influence on such men as Alfred E. Stearns, ’94, Harlan F. Stone, ’94, Calvin Coolidge, ’95, Dwight W. Morrow, ’95, and many other distinguished graduates of that period, cannot be overestimated. He has rightly been described as ‘a scholar with a keenly analytical mind, a masterly power of synthesis, and an ardent love of truth.”

His tenuous health required special care, creating an artificially tropical temperature in his room to protect his throat, riding in closed buggies and wearing a heavy coat and scarf even through the heat of summer. His infrequent public appearances combined with these eccentricities to create an atmosphere of mystery around the kindly man. “His heart was warm,” Fuess notes, “and he performed many good deeds which were never revealed.” It has been observed that the surest indication of a great teacher is preserved in the lives of his students. By such a test, Garman was one of the truly great. “He was to his pupils himself a model of intellectual curiosity, of tolerance, of idealism, whom they were eager to emulate.” Despite never publishing anything in his lifetime, the Amherst class of 1908, one of his last, set a tablet in the College Church inscribed with the simple tribute, “He chose to write on living men’s hearts.” The class of 1884 together with Garman’s widow prepared the only volume of his lectures, addresses and letters for publication in 1909, two years after his passing.

“But,” as Fuess continues, “in a very definite sense he still lives. Justice Stone declared recently that his work on the Supreme Bench had naturally brought him in touch with what were supposed to be the best brains in the country, but that he had yet to encounter an intellect that he considered equal to Garman’s. Coolidge is even more specific in his assessment of the man,

“We looked upon Garman as a man who walked with God. His course was a demonstration of the existence of a personal God, of our power to know Him, of the Divine immanence, and of the complete dependence of all the universe on Him as the Creator and Father ‘in whom we live and move and have our being’…The conclusions which followed from this position were logical and inescapable. It sets man off in a separate kingdom from all the other creatures in the universe, and makes him a true son of God and a partaker of the Divine nature. This is the warrant for his freedom and the demonstration of his equality. It does not assume all are equal in degree but all are equal in kind. On that precept rests a foundation for democracy that cannot be shaken. It justifies faith in the people…I know that in experience it has worked…In time of crisis my belief that people can know the truth, that when it is presented to them they must accept it, has saved me from many of the counsels of expediency.”

“…In ethics he taught us that there is a standard of righteousness, that might does not make right, that the end does not justify the means that expediency as a working principle is bound to fail. The only hope of perfecting human relationship is in accordance with the law of service under which men are not so solicitious about what they shall get as they are about what they shall give. Yet people are entitled to the rewards of their industry. What they earn is theirs, no matter how small or how great. But the possession of property carries the obligation to use it in a larger service. For a man not to recognize the truth, not to be obedient to law, not to render allegiance to the State, is for him to be at war with his own nature, to commit suicide. That is why ‘the wages of sin is death.’ Unless we live rationally we perish, physically, mentally, spiritually.

“…A great deal of emphasis was placed on the necessity and dignity of work. Our talents are given us in order that we may serve ourselves and our fellow men. Work is the expression of intelligent action for a specified end. It is not industry, but idleness, that is degrading. All kinds of work from the most menial service to the most exalted station are alike honorable. One of the earliest mandates laid on the human race was to subdue the earth. That meant work.

“If he was not in accord with some of the current teachings about religion, he gave to his class a foundation for the firmest religious convictions. He presented no mysteries or dogmas and never asked us to take a theory on faith, but supported every position by facts and logic. He believed in the Bible and constantly quoted it to illustrate his position.” In fact, to the surprise of all, he opened his remarks to the senior class of 1904 in chapel service with the unapologetic admission, “Believing as I do in the divinity of our Lord and Saviour, Jesus Christ…” Coolidge continues, “He divested religion and science of any conflict with each other, and showed that each rested on the common basis of our ability to know the truth.”

“To Garman,” Coolidge wrote, “was given a power which took his class up into a high mountain of spiritual life and left them alone with God. In him was no pride of opinion, no atom of selfishness.” Finishing his course students discovered what commencement meant as they stepped from formal education into the beginnings of “their efforts to serve their fellow men in the practical affairs of life.” Some professors expect fawning adulation, gathering followers devoted to one’s personality rather those who will take what they can from him while continuing to think for themselves, building on what they had learned. A cult of personality was not Charles Garman. He was not the Alpha and Omega of all that life had to teach. Christ more than adequately held unchallenged title to that. Garman expected his course “to be supplemented. He was fond of referring to it as a mansion not made with hands, incomplete, but sufficient for our spiritual habitation. What he revealed to us of the nature of God and man will stand. Against it ‘the gates of hell shall not prevail.’ “

“As I look back upon the college I am more and more impressed with the strength of its faculty, with their power for good. Perhaps it has men now with a broader preliminary training, though they then were profound scholars, perhaps it has men of keener intellects though they then were very exact in their reasoning, but the great distinguishing mark of all of them was that they were men of character.” Perhaps that is the ultimate explanation to Fuess’ query as to what made Amherst so unique among America’s colleges and universities in the 1880s and 1890s. It was principally the character of the men who taught — and learned — there that so special an environment existed for the development of the whole person, so capable of producing “such a large proportion of famous men” who would go on to lead successful lives, leaving indelible marks through their service in business, law, ministry, and government (Amherst, pp.244-5).

Justice Stone, writing to Fuess, confirms this estimation, “I think you and President Coolidge understand the case. After forty years of contact with all sorts of men both in and out of educational institutions, Garman, Morse, and ‘Old Ty’ are still in my opinion great men…” What made men and institutions great was not in some mystical attachment to “hocus pocus” or the nostalgia of youth, it was anchored firmly in the integrity of men like Garman whose reasoned conclusions merit renewed study and consideration. Experience has proven them to be more prescient and enduring than we may realize. Coolidge would agree.

“He was constantly reminding us that the spirit was willing but the flesh was strong, but that nevertheless, if we would continue steadfastly to think on these things we would be changed from glory to glory through increasing intellectual and moral power. He was right” — Calvin Coolidge on Charles Edward Garman, The Autobiography, (New York: Cosmopolitan, 1929, p.69).

For further reading

Booraem V, Hendrik. The Provincial: Calvin Coolidge and His World, 1885-1895. Lewisburg: Bucknell University Press, 1994.

Fuess, Claude Moore. Amherst: The Story of a New England College. Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1935.

Garman, Eliza Miner. Letters, Lectures and Addresses of Charles Edward Garman: A Memorial Volume. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1909.

Waterhouse, John Almon. Calvin Coolidge Meets Charles Edward Garman. Rutland, VT: Academy Books, 1984.