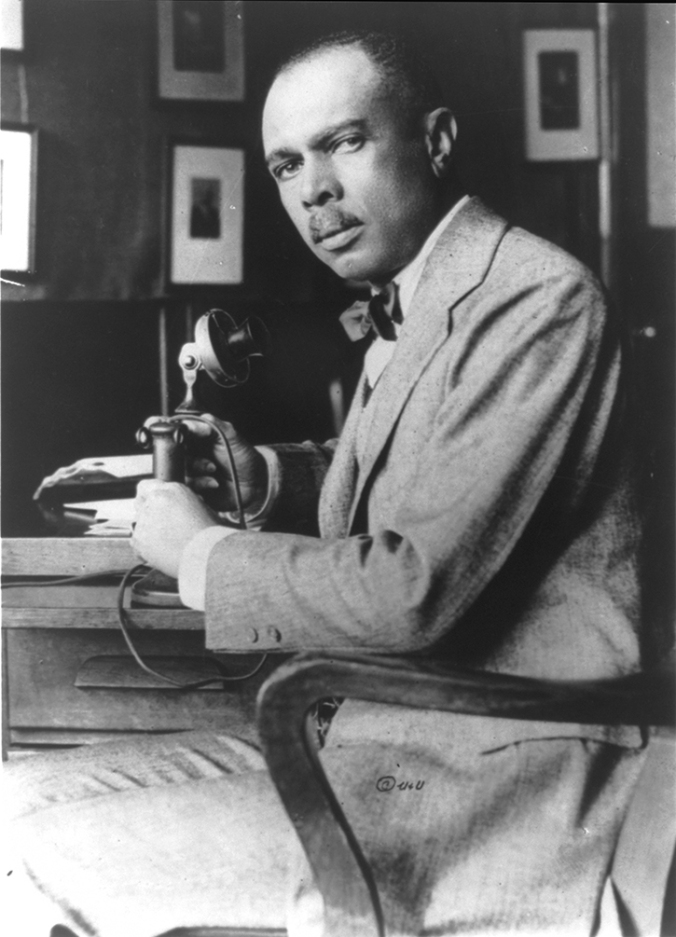

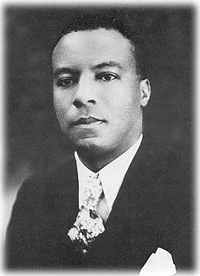

James Weldon Johnson, head of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. Photo taken around 1920.

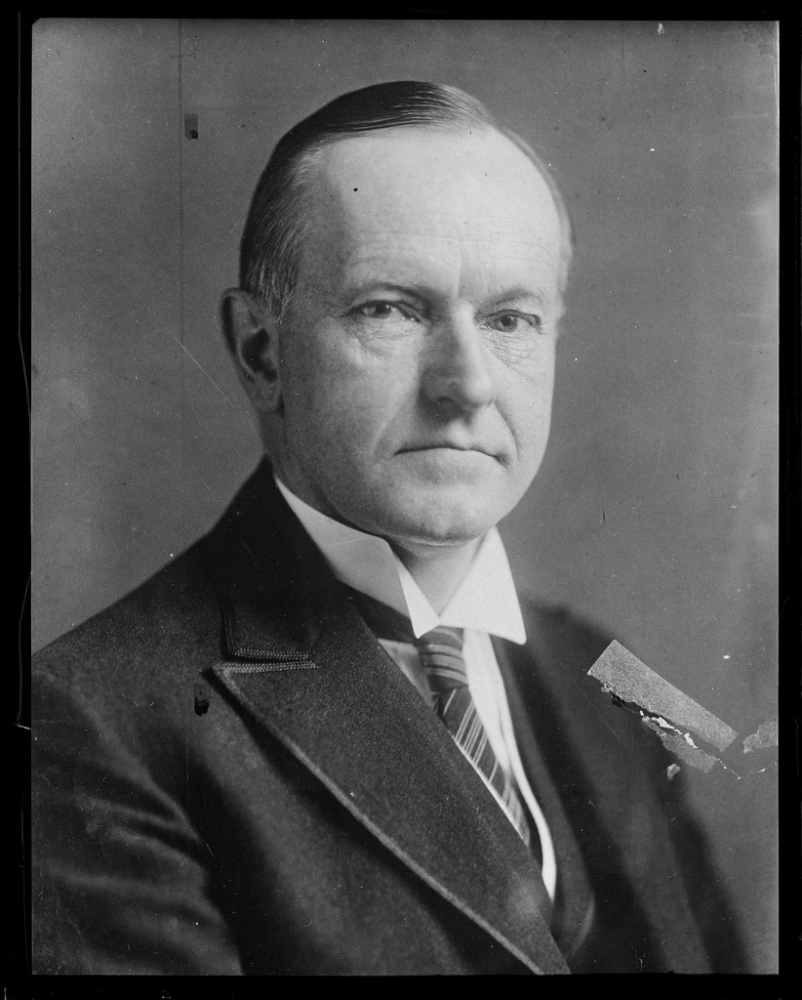

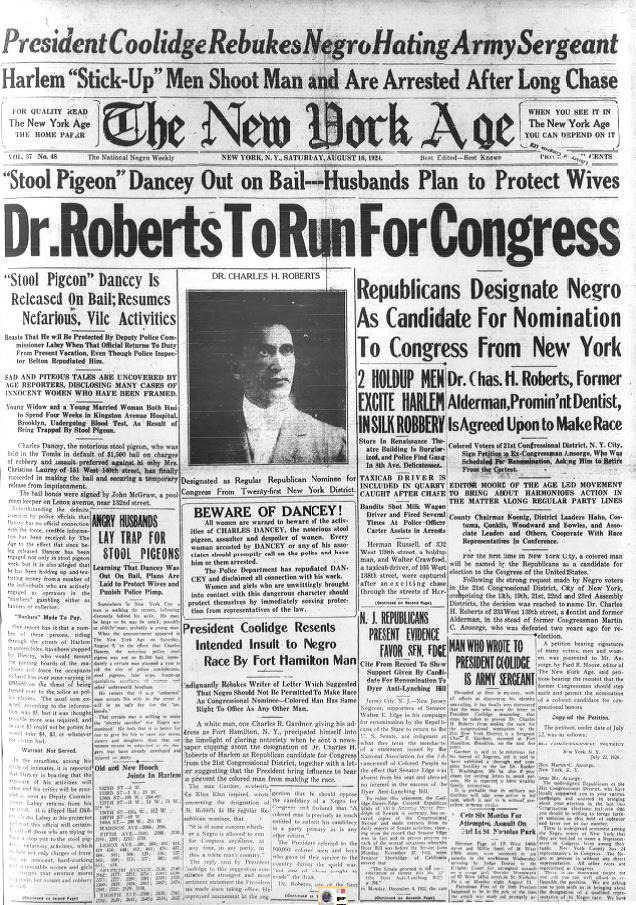

When it was arranged for James Weldon Johnson, the first black leader of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, to visit the White House in the early months of the Coolidge Administration, Mr. Johnson was not only glad to leave but, unfortunately, left with a completely mistaken perception of the President. Even more unfortunate, Johnson let that first impression influence future interaction with the Vermonter. Johnson wrote years later of this meeting,

“He, it appeared, did not want to say anything or did not know just what to say, I was expecting that he would make, at least, any inquiry or two about the state of mind and condition of the twelve million Negro citizens of the United States. I judged that curiosity, if not interest, would make for that much conversation. The pause was painful (for me at least) and I led off with some informational remarks; but it was clear that Mr. Coolidge knew absolutely nothing about colored people. I gathered that the only living Negro he had heard anything about was Major Moton (Booker T. Washington’s successor at Tuskegee). I was relieved when the brief audience was over, and I suppose Mr. Coolidge was, too.”

William Monroe Trotter, the fiery editor of the Boston Guardian. Coolidge had come across Mr. Trotter back in the Massachusetts Senate days in 1915.

Asa Philip Randolph of the preeminent news source, The Messenger, would go on to lead the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters in 1925. Randolph had accompanied James W. Johnson on his visit to the White House in February 1924. He would become an elder statesman during the 1960s Civil Rights Movement.

William H. Lewis, standing, argues a case before a Massachusetts court, 1910s. He had graduated Amherst three years before Coolidge, who wrote his father at the time about Lewis’ skill as a football player, saving the college team on more than one occasion. Lewis, a Republican, failed to see why Coolidge would not verbally condemn the Klan in 1924. Coolidge’s subtle yet more effective approach to the problem prevailed.

Born a slave, Giles Beecher Jackson worked his way to freedom, becoming a Richmond attorney and relentless advocate for a Negro Industrial Commission, which (thanks to his efforts) found its way into the Republican platform of 1924. Coolidge endorsed his idea and urged Congress to create it in 1923. Regrettably, Mr. Jackson died without seeing it come to fruition. Coolidge, however, continued to remind Congress (and anyone who asked about it) of the importance of this joint effort started by Mr. Jackson.

While this short meeting illustrates the importance of an accurate understanding it also demonstrates the need for a healthy measure of forbearance. It underscores that even someone as eager for a good relationship between blacks and whites was still vulnerable to prejudice sometimes. As Alvin Felzenberg points out, Mr. Johnson was completely unaware of the broad network of associations already forged between Coolidge and quite a few black leaders in education, business and media, including such notables as William M. Trotter, editor of the Boston Guardian, Nahum B. Brascher, Editor-in-Chief of the Associated Negro Press, A. Philip Randolph of The Messenger, William H. Lewis (who had been an upperclassman at Amherst with Coolidge), Giles B. Jackson, who introduced the idea of a Negro Industrial Commission, and numerous other educators and public servants. Felzenberg reminds us that this was simply the Coolidge temperament, making no distinction between what color the visitor was. We recall that Frank Strearns’ initial impression of “Silent Cal” was not favorable either. One could say that Mr. Stearns was still trying to acclimate to Coolidge’s reticent habits years after becoming good friends with him. Coolidge learned not merely by engaging in conversation, but by observation. His keen judgment of people’s character worked through it all, the quiet and the loquacious times. A person’s presence could tell him volumes about the individual. He explains what he was doing in his Autobiography,

“I called in a great many people from all the different walks of life over the country…It has been my policy to seek information and advice wherever I could find it. I have never relied on any particular person to be my unofficial adviser. I have let the merits of each case and the soundness of all advice speak for themselves” (p.188).

From the very earliest days in state government through his years in the White House, it became apparent to those who followed his career that Coolidge simply did not “slop over” with enthusiastic guarantees for anyone, regardless of who they were. A master of time management, he listened carefully, remained polite but curt and then followed up quietly without any of the standard operating procedures expected of politicians. This was what unsettled Mr. Johnson most and he never quite understood it. Consequently, we of today should not be so quick to condemn circumstances or people when, at the time, even the most dedicated leaders were struggling to understand each other accurately, addressing how to solve problems and determining what were the best means for everyone to move forward. The twelve million “colored” people in America no more agreed on one, solitary solution than did the rest of the country. It is a mistake to assume one-size-fits-all fixes from Coolidge or anyone else in Washington were capable of resolving each issue…especially when it involves people.

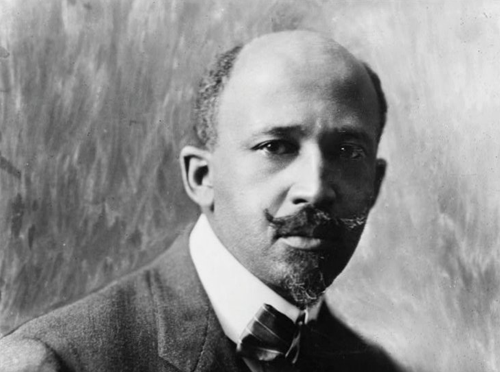

William Edward Burghardt DuBois (pronounced Doo-boyz) helped found the NAACP in 1909 and was a seminal influence on what was to be done about race relations in the twentieth century. Coolidge sought to include him in diplomatic work but Dr. DuBois declined to be part of what he considered a rigged political system. By refusing to participate, he unwittingly helped thwart the mechanism for an expression of popular government through party principles. He too, underestimated Coolidge’s courage and willingness to tackle the tough political questions between blacks and whites.

The “black community” of the 1920s was anything but monolithic. The death of Booker T. Washington in 1915 had left a vacuum of leadership and direction. Still, many wise and able leaders had stepped forward since the formal emancipation. Veteran reformer, W. E. B. DuBois, continued to work, write and influence the movement toward more drastic changes than the political process or economic growth could accomplish, he felt. Ever the skeptic, DuBois wanted sweeping action taken to right the wrongs through social justice. It would not happen by merely helping blacks help themselves improve through vocational training, commerce, and political involvement. For DuBois, it demanded expansive changes to society. Nevertheless, despite criticism by DuBois and others, real successes in a short seventy years could be claimed. Much remained to be done but it did not negate the very significant advances experienced by blacks through education, hard work and engaged civic participation. The path to addressing the problems in race relations was by no means clearly marked. We, who look back on the past, often mistake the hindsight of the present with the clarity of what should have been known and done at the time. This is but another form of prejudicial perception: interpreting what has been through the lens what now is.

Some favored a segregated civil service, like black attorney Perry W. Howard, while others sought a broad executive order to ban all discrimination and bigotry in government. Making the despicable act of lynching a Federal crime was paramount to many, including Coolidge himself, who considered the constitutional question of declaring martial law to confront areas especially rampant with lynching. Still others, distrustful of either political party, sought the development of literature and the arts as the means to racial equality, like James W. Johnson and the NAACP. Some believed that economic development should remain secondary to social and political changes, emphasizing the reform of voting rights and “Jim Crow” laws ahead of the self-help made possible by a strong educational and commercial effort, as exemplified by Booker T. Washington’s Tuskegee Institute, Howard University and other “colored” organizations. Even Marcus Garvey, directing the vibrant 400,000 member Universal Negro Improvement Association, gravitated to this concept of self-sufficiency applying it to a drastic break from American laws and institutions for a solution less committed to improving conditions in this country than to establishing a nationalist identity independent of the “white man’s” America. Yet, in 1927, it was Coolidge who commuted Garvey’s sentence of imprisonment for mail fraud, a penalty meted out by Wilson’s xenophobic Justice Department.

Marcus Garvey, native-born Jamaican, established and led the Universal Negro Improvement Association. Many, including DuBois, perceived him as a dire threat to blacks everywhere. This photograph was taken in the summer of 1924. He would leave his mark on movements around the world, including the Rastafari movement, which considers him a prophet. His second wife, Amy Jacques Garvey, petitioned President Coolidge for his release, which was granted in November 1927 followed by deportation back to Jamaica.

The Veterans’ Hospital was another trouble spot early in the Coolidge Administration. Led by an overtly bigoted official, the proposal among blacks and whites to temporarily keep segregation ensured that everyone received the care they needed without partiality or discrimination. The decisive action taken by Coolidge on this, as with the other specific moves to stop discrimination on his watch, will be discussed in the next part of our series. Yet, his energy to act in concert with those who did not always agree with him like William M. Trotter and William H. Lewis, using the talents of men like Emmett Jay Scott and William Matthews on behalf of the abused and aggrieved has been largely suppressed since it fails to neatly fit with the accepted narrative of a “racist white, Anglo-Saxon, Protestant” Republican Party and President. Prejudiced by ideology instead of honesty about the actual record, too many historians have mistaken, like the unfortunate James W. Johnson, a first impression of Cal’s “inactive” approach with the complete picture of Coolidge, the man and what he actually did about race relations.

In the third part of this series, we will examine in further detail how Coolidge responded to racial conflicts and helped lay a foundation for progress grounded in Christian forbearance, humility and voluntary collaboration. By emphasizing the respect we owe our neighbor, whatever race or color, and promoting constructive opportunities rather than perpetuating a victim mentality, more was done for people as the unique individuals we all are than the approach taken in subsequent decades to corral everyone into a collective existence centered around the determinations of what is “just” and “equal” from Washington.