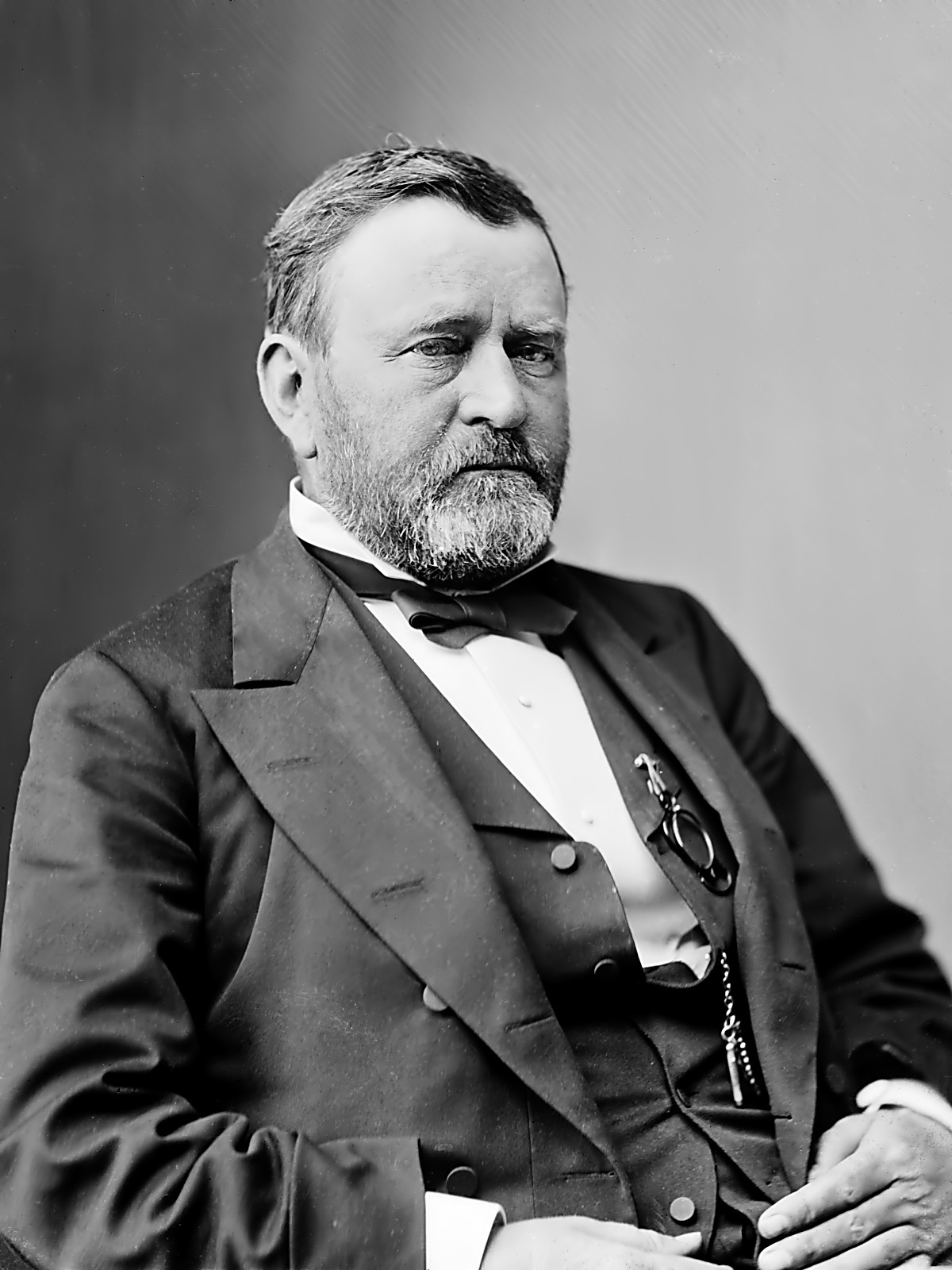

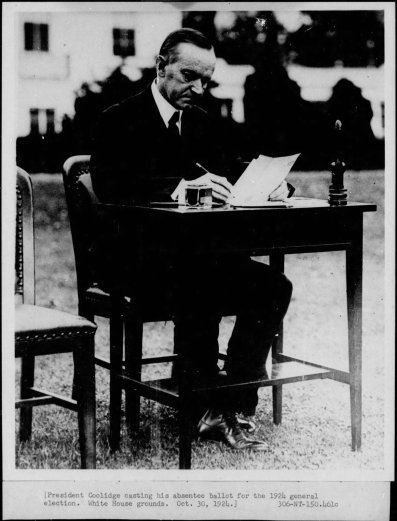

Dedication of the Grant Memorial near the foot of the Capitol Building, where Vice President Coolidge delivered these remarks, 1922.

Ninety-two years ago, 1922, marked the occasion Vice President Coolidge dedicated the Monument to General Ulysses S. Grant in Washington, coinciding with the centennial of President Grant’s birthday, April 27. As with many of his predecessors in the Presidency, Coolidge (though yet to rise to that great office) would have some very thoughtful and profound assessments of the man and his contributions to our institutions, our republican system and to liberty itself.

Grant was, and rightly belongs, among those we honor as a “great American, who was sent into the world endowed with a greatness easy to understand, yet difficult to describe: the highest type of intellectual power–simplicity and directness; the highest type of character–fidelity and honesty. He will forever hold the admiration of a people in whom these qualities abide. By the authority of the law of the land, with the approving loyalty of all his fellow countrymen, in the shadow of the dome of the Capitol which his work proved and glorified fittingly, flanked on either side by a group of soldiers in action, looking out toward the monuments of Washington and Lincoln, this statue rises to the memory of General Ulysses Simpson Grant. It is here because a great people responded to a great man.”

“…He had the ordinary experiences of the son of an average home maintained by a moderately prosperous business. He went to West Point, not so much with the purpose of becoming a soldier as from a desire to secure an education. He liked horses and rode well. He did not appear brilliant, but he had industry. He worked. He made progress. He had that common sense which overcame obstacles. After his graduation he remained in the army for eleven years, rising to the rank of captain” serving through the Mexican War, resigning voluntarily in 1854. “Destiny sent him to private life, where he could better feel the rising tide of freedom. The next few years he spent as a farmer and a business man. He still worked hard, but he did not prosper, scarcely making a living. He had little taste for small things; it required an emergency to call forth his powers.” The “great crisis” of Union found him in Illinois, working his father’s craft, leather. Volunteering himself again, he declared, ‘Whatever may have been my political opinions before, I have but one sentiment now. That is, we have a government and laws, and a flag, and they must all be sustained.’

Appointed by the Governor to lead the 21st Illinois Regiment, he took command with characteristic directness, ” ‘Men, go to your quarters.’ Within four years he was to be recognized as the greatest soldier in the world.” His capture of Fort Henry and Fort Donelson, his struggle at Pittsburgh Landing and finally his success at the surrender of Vicksburg combined to make Grant a major-general in the regular army. However, it was at Lookout Mountain and his maneuvers at Chattanooga that “demonstrated his great military genius, both of plan and execution.” The following March would find him taking command of the Army of the Potomac, unleashing “blow upon blow from the Wilderness to Appomattox…”

“…His work finished, though the President had invited him to attend the theatre, he left the city on that fatal evening of April 14. He mourned the loss of Lincoln, but his first allegiance was to his country. His attitude toward Johnson was all that could be required of a general toward his commander-in-chief, until the President, seeking to embroil him in his own political disputes, charged him with bad faith…While Johnson sank in the public estimation, Grant rose, being unanimously nominated and handsomely elected President of the United States.” Coolidge was four months old. As a boy, he would acquire a deepening respect the more he learned of the first President he would recall in youth.

Grant “had little taste for political manuevres. He found his eight years fell on a time of confusion, both of thought and action. He worked as best he could with the contending elements which made up Congress…Although he broke with a well-meaning reform element of his party, which supported Horace Greeley, he was triumphantly re-elected. One of the important contributions which he made to the public service was his veto of the bill which provided for the inflation of the currency by issuing $400,000,000 in greenbacks. At a time when the political ideals of the country were very low, President Grant held to his own high standard of honorable public service…”

“…Through the contested election of Hayes and Tilden, in 1876, he took a course marked by a high spirit of patriotism. ‘No man worthy of the office of President, should be willing to hold it if counted in or placed there by fraud. Either party can afford to be disappointed in the result. The country cannot afford to have the result tainted by the suspicion of illegal or false returns.’ When the man who knew how to command armies took this position for the enforcement of the law, the country stood behind him and peacefully accepted the decision of the electoral commission.”

“His closing years were marked with great tragedy. Betrayed by one whom he trusted, he saw his property dissipated and large obligations incurred. A lingering and fatal malady added anguish of the body to the anguish of his soul. Never was he greater than in these last days. With high courage, without complaint, on a bed of pain, seeking to retrieve his losses, he was preparing his memoirs…He was still thinking of his country, not as a partisan but as a patriot, not even as the general the armies he had led but as an American.” Being near death, he observed, “I have witnessed since my illness, just what I have wished to see since the end of the war–harmony and good-will between the sections.”

“…Great as he had been, his armies had been greater still…As they supported him in the field, their bronze forms support him here.”

Coolidge would reflect on Grant’s great enemy, General Robert E. Lee, seeing two equally noble champions of integrity, recalling that both reflected what was best about America just when it was most needed.

“Men are made in no small degree by their adversaries. Grant had great adversaries. They fought with a dash and a tenacity, with a gallantry and an enduring purpose which the world has known in Americans, and in Americans alone. At their head rode General Robert E. Lee, marked with a purity of soul and a high sense of personal honor which no true American would ever stoop to question. No force ever quelled their intrepid spirit. They gave their loyalty voluntarily or they did not give it at all.”

“It is not so much the greatness of Grant as a soldier but his greatness as a man, not so much his greatness in war as his greatness in peace, the consideration, the tenderness, the human sympathy which he showed toward them from the day of their submission, refusing the surrender of Lee’s sword, leaving the men of the Southern army in possession of their own horses, which appealed to that sentiment of reconciliation which has long since been complete. It was not a humiliation but an honor to remain under the sovereignty of a flag which was borne by such a commander…”

Summing up the significance of this great American and honorable President, never an easy task, seems effortless in the words of Coolidge,

“Our country and the world may well consider the simplicity and directness which marked the greatness of General Grant. In war his object was the destruction of the opposing army. He knew his task was difficult. He knew that the price would be high; yet amid abuse and criticism, amid misunderstanding and jealousy, he did not alter his course. He paid the price. He accomplished the result. He wasted no time in attempting to find some substitute for victory. He held fast to the same principle in time of peace. Around him was the destruction which the war had wrought…He refused to seek refuge in any fictions. He knew that sound money values and a sound economic condition could not be created by law alone but only through the long and toilsome application of human effort put forth under wise law. He knew that his country could not legislate out its destiny but must work out its destiny…His policy was simple and direct, and eternally true. In the important decisions of his life his fidelity and honesty are equally apparent…He never betrayed a trust and he never deserted a friend. He considered that the true test of a friend was to stand by him when he was in need. When financial misfortunes overtook him he discharged his obligations from whatever property he and his family could raise. Here was a man who lived the great realities of life…There was no artifice about him, no pretense, and no sham. Through and through he was genuine. He represented power.”

“A grateful republic has raised this monument not as a symbol of war but as a symbol of peace. Not the false security, which may come from temporizing, from compromise, or from evasion, but that true and enduring tranquility which is the result of a victorious righteousness. The issues of the world must be met and met squarely. The forces of evil do not disdain preparation, they are always prepared and always preparing…The welfare of America, the cause of civilization will forever require the contribution of some part of the life of all our citizens to the natural, the necessary, and the inevitable demand for the defense of the right and the truth. There is no substitute for a militant freedom. The only alternative is submission and slavery.” What Grant gave, “America shall give.”