Once asked whether this author considered Senator Robert A. Taft to be the political/philosophical heir of Calvin Coolidge, I answered that Cal has no heir. He was unique and the idea that anyone could (or should) replicate Coolidge would be missing the mark, especially in his estimation. This doesn’t mean that his principles and qualities of character do not belong in public life again. They are gravely needed. Public questions are furnished by an array of leaders but each are raised for the needs of their generation. Nevertheless, Coolidge, as well as Taft, believed in proven and enduring principles — they were some of the few consistent ones to do so — and they also saw alike when it came to the strength of leadership at any given time. It does not rest on personality – the gravitas and popularity of a particular person – but on the precepts and principles of our Republic’s form of government. To them, the power of party or government administration was a dangerous weapon when one person became the indispensable savior or asset of the country.

This begins to reveal a powerful similarity between these two men that goes beyond the superficial. They shared a common mind and approach to public service. Both men led through war-time legislatures, striving to keep constitutional limits on their governments even in the midst of waging war, showing that our laws did not merely function in peacetime. Coolidge had extensive executive experience while Taft would lead legislative bodies but not direct executive ones. Both would lead following wartime upheaval, however, working to restore peacetime policies and scale back the militant agencies of Washington, whether it be the “alphabet soup” programs of the New Deal or Wilson’s “New Freedom” agenda. Both men rose to office at a time of national depression and stood against the tactics of those who would make wartime procedures permanent, consolidate bureaucracy and strip the individual of one’s rights and responsibilities. Both men saw rights and responsibilities as inseparably linked. One man’s freedom could not trample on the rights of others’ freedoms. Freedom would not remain free if one man’s freedoms were permitted to trample that of others, even when that meant expressing an unpopular thought or opinion.

A laissez-faire “free market” system was not absolute or even paramount to both men, who recognized a higher law of service that could not justly reorient a freedom to trade above other civil liberties. They showed no favors to the interests of their day, including the business libertarians of their time. They both insisted that something more than materialism, something transcending all the emphasis on a standard of living, was being overlooked and lost in the shuffle. It was not only ever economics to Coolidge or Taft. The simple morals and public virtue were of greater importance. These do not rely on affluence or prosperity for their validity and sustenance. Things did not make us better people. The development of character and the improvement of culture did. These are things government could not compensate for or supply. It remained where it always will to curb and correct: in the hands of the people. The emphasis on things was losing sight of what mattered far more, just as Coolidge had warned and Taft would reiterate.

Both believed in doing the day’s work and standing on what is right regardless of what votes were not “courted” or whose support did something for them. The right to join a union was just as important as the right to choose not to, coercive interests could not rightly compel an individual to do either. They both knew laws had limits. Law could no more reform human nature than a government bureau could competently handle only the job it was created to supervise. It was this unshakable sense of justice to all parties that lifted Coolidge and later Taft high in the estimation of even their political opponents. Yet, both men were unapologetic partisans, believing that the sovereignty of popular government is best represented in the party system. Both men constantly declared that principle, not expediency, had to drive the parties or else government by The People would break down. No other system would preserve freedom and order. A single-party state posed as much threat as a bureaucratic playground that took decision-making out of party principles and publicly pledged policies into an unaccountable and arbitrary rule by the few. Both men pointed back to self-government, the working out of one’s own salvation, rather than empowering some authority to take custody of it for you. They knew that government could not assume a part of the burden of the people or their business affairs without ultimately taking control of people and the market. Coolidge and Taft espoused a more profound and innovative progress – one grounded by the Founding – than that of the rigid, doctrinaire policymakers of the FDR and Truman administrations.

Both men held steadfastly to the practical and real. While others would ask them about some theoretical abstraction, they would kindly but simply dismiss it. They were not concerned with mere academic constructions or “what if” scenarios that sought to redesign society on paper, they were engaged and most concerned in the daily task of doing, working out public problems with principle and courage. That courage would manifest in two similar occasions. Coolidge would cast the tie-breaking vote that banned showing the racist film, “Birth of A Nation” in Boston. Taft would successfully oppose the admission to the Senate of a race-baiting Democrat, who had stolen the election by intimidating blacks in Mississippi. Neither man would tolerate or look the other way when racial prejudice sought acclaim. They shared an acute sense of justice that stood up for anti-lynching bills throughout their careers, not because it would curry favor but because it was justice that not even local government has authority to deprive (from emotional prejudice) any man of his life and liberty. Taft’s opposition to the Nuremberg Trials came not from any support for what the German high command had done but from his keen regard for true justice. He opposed the court’s barely concealed search to retroactively punish those who lost the war while absolving the Allies at the hands not of impartial law or due process but through a lynch mob. To Taft, victor’s justice was not justice at all. It was Versailles all over again.

Taft upheld the principle that segregation in schools was a clear denial of every man’s equality under the law yet, when it collided with his principle that education be left to the States, as Coolidge held before him (rather than imposed and directed from Washington), he held course and declared that for Federal authority to trump the States (however well-intentioned) would likewise be an unconstitutional grab of power. It had to change from the people upwards not down from Court ruling or legislative act. This was no popular stance even then but in light of the social and cultural turmoil of mandatory busing and other Great Society programs for community reorganization, Taft (and Coolidge) stand vindicated on the side of the regular folks whose lives are largely worse than before Washington got involved.

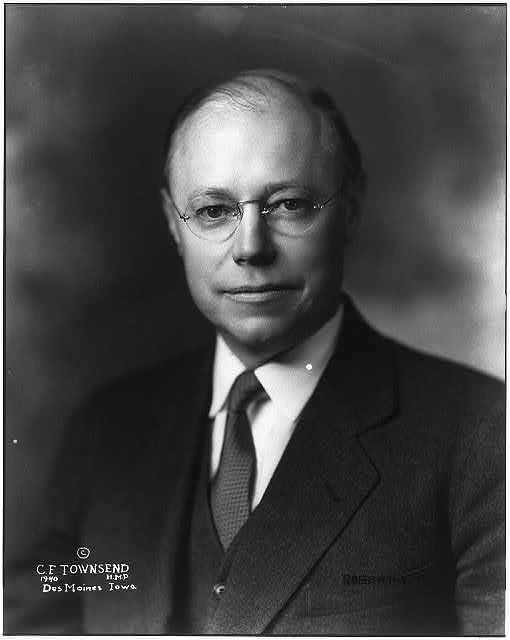

Senator Taft shortly after taking office in the Senate, 1939. He hit the ground running and took many by surprise with his thoroughly reasoned and original critiques of what had gone virtually unopposed by anyone in Congress for six years before he arrived. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Both were masters of debate, adept at mustering facts and figures to bear on complex issues needing practical analysis. Both saw the limits of Federal power and spoke when it was time to speak. Neither possessed that “flash-in-the-pan” persona but both were steady, level-headed, genuine, and diligent. While Taft never saw the Presidency (as his father had) and seemed to be followed not by “Coolidge luck” but by a recurring battle against weak, “me too” liberal Republican candidates (from Landon to Willkie to Dewey to Eisenhower), Taft had the overwhelming support of those in the trenches, just as Cal did. It was the state and county committee members who wanted Taft. The same fight being waged now for the path to victory was argued then by Taft who insisted that contrast not concession, principle instead of pandering was the answer. No favors were done by accepting the premise that Democrat Big Government was acceptable, had popular support, and could not be overturned and so could only be better managed not opposed. Taft rejected this premise and from 1938 onward was the voice for principle in Congress.

He was the voice for common sense that had been missing for six years against what seemed to be an unstoppable barrage of activities attacking the foundations of the American system of government. Together with conservative Democrats he halted the advance of any more New Deal programs. FDR never got another domestic policy through after that. Had it not been for the onset of World War II, FDR’s utter failure would have no where to hide today. When the White House turned abroad to embrace an expansionist foreign policy, assuming Europe’s problems, Taft took up the warnings against confusing American interests with those of the Old World. His reasoning against U.S. intervention sounded provincial by some at the time but it overlooks that he was speaking for a majority of Americans opposed — for very good reasons — to fighting yet another European war. Time has affirmed Taft’s insistence that American interests be specifically explained and directly involved before the nation goes to war.

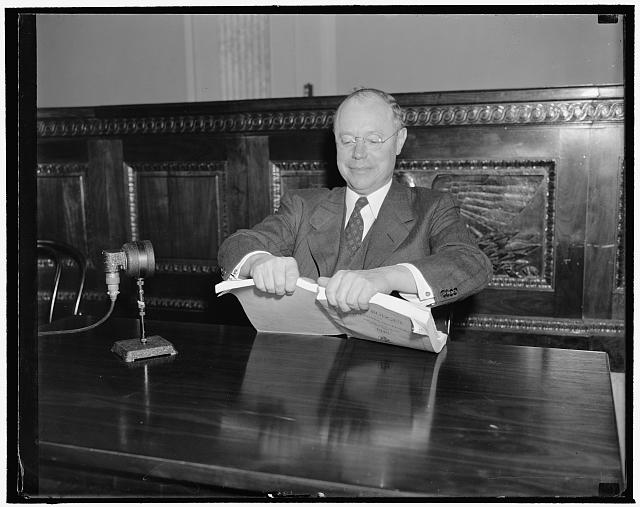

Senator Taft tearing apart the 1940 Budget. He fought for balance against an ever-growing deficit each year of the FDR administration.

Taft would continue the fight after the War for liberty without special provisions for select groups, just as Cal had. He prevented the Universal Military Training measure that would have required military training for every young man in America, a wartime power to enforce conformity in peacetime reprehensible to liberty, Taft believed. It is unfortunate that death took Taft so soon, not unlike it did in Cal’s case. However, both men stand on either side of the expansive edifice of the New Deal ideology for which we are still paying culturally, morally, and politically. Together they condemn it, reveal its deep and fundamental flaws, and appeal (seemingly in the wilderness these days) to that true course of limited governance, constitutional freedom, and the rights and responsibilities of citizenship. They warn Republican leaders of the danger in diluting principled party resistance for a distinction without a difference. They exemplify a courage and integrity that make them statesmen for our time as well as their own not simply self-serving, opportunistic office holders. They stand their ground, joined by Democrats who see past the moment to the larger issues at stake, the bigger principles that would tear the country apart and drag it down into an arbitrary and despotic future if they failed to recognize there remains a clear and unmistakable limit, a Constitutional one, to what government can do.

So, was Bob Taft the political heir of Calvin Coolidge? He certainly came closer than anyone else did during the 30s, 40s, and 50s. We suggest two great books: 1. The Political Principles of Robert A. Taft by Russell Kirk and James McClellan (New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers, 2010; new edition of a 1967 classic) and 2. The Coolidge equivalent of the first book, Why Coolidge Matters: Leadership Lessons from America’s Most Underrated President by Charles C. Johnson (New York: Encounter Books, 2013). Read them and decide for yourself.