Charles Lindbergh lived an incredible life. Born in 1902, just before the discovery of flight by the Wright brothers, he would live to see not only the Apollo launches but the successful entry of Skylab into space, Lindbergh passing away in 1974. His work developing aviation to transcontinental and then intercontinental reach, his design of the perfusion pump, his gathering of intel on German and Russian air capabilities, his numerous survey flights around the world, his Corsair combat missions with the Marines in the Pacific and the contributions he gave to the development of rocket technology are just some of what make Lindbergh’s mark on modernity so felt even today.

The source of his fame, the incredible solo crossing of the Atlantic in his customized monoplane Spirit of St. Louis, opened doors he never imagined and changed the course of his life more than once. President Coolidge is a minor character in this recounting of his life, Lindbergh’s last autobiographical rendering, occurring only four times in connection with the President’s ordering the aviator home from Paris aboard the massive cruiser Memphis. Coolidge would first meet him at age 25, already having accomplished a great deal as an officer of the Air Corps and mail delivery pilot. His use of Lindbergh as a kind of aviation ambassador led, indirectly, to his meeting Dwight Morrow’s second daughter, Anne, on his flight to Mexico City.

Coolidge would successfully shepherd the advancement of aviation in his own sphere while Lindbergh took on the task of technical adviser to commercial and military applications of its growth and power. Wishing to travel more of Europe and at first chagrined that his plane, having made the primacy of oceangoing vessels obsolete, Lindbergh notes how the past seemed to be recapturing and mastering the future. That was only a temporary impression. Lindbergh finds the trip back to Washington to be rewarding to his curious and inquisitive mind.

The relentless acclaim and intense loss of privacy came as an understandable shock to him, a cost of his accomplishments few understood let alone respected. It resulted in tragedy: the kidnapping and murder of the Lindbergh’s first baby and the despicable media attention toward his second son forced them to leave America for seclusion in Europe. This combined with his confrontation of President Roosevelt regarding the disastrous air mail order and his secret travels – gathering intelligence on the German war machine – combined to further destroy his reputation in the eyes of many. The Autobiography explains each of these instances and shows how, properly understood, he merits our sympathies in this regard not our condemnation in historical memory.

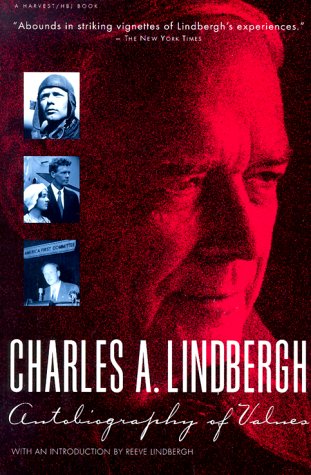

Lindbergh and his mother are guests of President and Mrs. Coolidge at the temporary White House at Dupont Circle, June 11, 1927.

His unpersuasive worldview, however, cultivated since childhood, leaves the reader empty and uninspired. He was clearly a man who had followed Rousseau’s autonomous humanism to its twentieth century conclusions only to step back from the precipice and be unable to explain how he got there and how to find a way out that was coherent and consistent with his hopeful faith in science to save. He admits the dehumanizing results of science when embraced without an objective source of values, leaving man as so much machinery in an impersonalized universe. He continues course to find that this readily leads civilization to its own destruction before an impersonal universe and values-neutral natural selection of the fittest genes. His story of the baby elephant and the Masai’s obstruction of better genetic material illustrate this dismal conclusion. Man and nature are ripped from their proper proportions and reality is impossible to decipher from non-reality or “dream,” as Lindbergh calls it. This is right where humanist man found himself in the twentieth century. Having removed what was rationalized to be religious superstition and Biblical myths, a replacement for objective truth and source of values had to be found. Man, first placing it in himself and his powers of reasoning learned the horrible results of his power unchecked by moral obligations in what was the Christian worldview. It was a worldview where man’s values come by being made in the image of God, God has spoken in the Bible, through Christ we have the redemption from a fallen world, and in Him we discover an ordered universe (with ourselves and nature in proper place) with all its unity of coherence, its cause and effect, its meaning and worth.

Lindbergh, hamstrung by his own worldview, could only see the terrors of Hitler’s regime as misguided or lacking balance, evil would be too strong a term when such values as good and bad, right and wrong were not only passe but incompatible with his relativity of value judgments. Of course, while he suggested leaving all he knew for the jungle, he did not live the way he spoke or wrote. He could not. Even Sartre and Gauguin could not find a consistent existence from their worldviews. Lindbergh could not bring himself to take the leap with humanist man off the cliff into post-modernity with all its fragmentation, pessimism, and apathy. For all of his rhetoric in this book, he remained stuck at the impasse, left only with non-reason as his feeble consolation. To do so he must deny the identity and value of the individual for the irrational concepts of Hindu and Buddhist absorption into collective identity with the objects of the universe. Man is not man, he has descended to the meaningless and impersonal identity of mere material masses that somehow pass the knowledge and enlightenment of the ages genetically while becoming one with everything around us. This bleak picture is all Lindbergh leaves for us as he ends his book.

It is a worldview Coolidge would not have countenanced, even with all he loss and grief he suffered, having retained his clear grasp of reality in faith and our important place in a universe God lovingly created and continued to nurture through the darkest of times. It was man’s fallibility and sinfulness that ushered in all the death, suffering, and turmoil. Within the Christian worldview, there was no less a wonder, curiosity, and joy in the complexity and beauty of the designed world, for the early scientists were inspired to learn more by their Christian worldview. Even Lindbergh’s simplistic view of the cell illustrates the aviator’s limited understanding of how complex the smallest designs are in our world. God did not tempt man, as Lindbergh claims, relegating him to the tyranny of his own awareness and knowledge. It was man’s will to enthrone himself and believe in his own perfectability that overthrew God’s good world and brought Lindbergh with the rest of modern man to the hopeless void he discovered. The actions of Christ, on the other hand, are what fueled Coolidge’s law of service and the obligations we have to each other, because we are beholden to what God has spoken and what Christ has done for us as individuals with eternal selves. For Coolidge, the love of God gives the values that so eluded humanist man. To Him we turn for the truth, and the real hope it gives, which nothing else can supply.