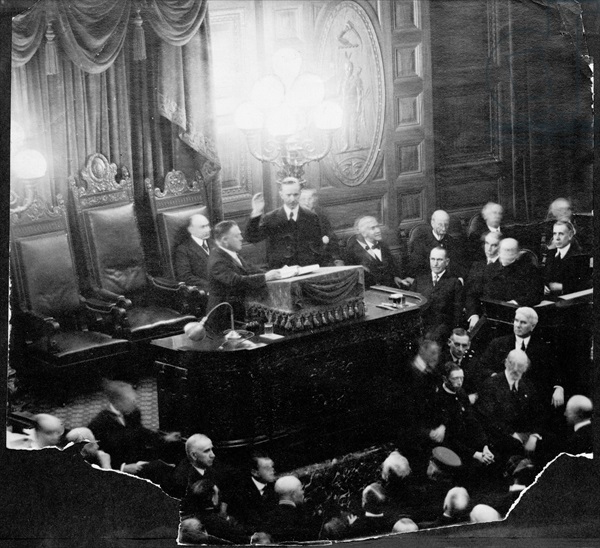

Calvin Coolidge (1873-1933), later taking the oath of office as Governor of the State, 1st January 1919. His father is seated beside the massive desk at right. This photo is often incorrectly shown reversed, making it appear as if Coolidge is raising his left hand to take the oath. Photo credit: American Antiquarian Society, Worcester, MA.

When Calvin Coolidge assumed office following the sudden death of Warren Harding in August 1923, it had not been the first time “President” was formally used to address Cal. Of course, his name had been touted by some leading up to and during the 1920 convention but before that Coolidge had been President of the Massachusetts Senate. Being the most prepared candidate for the Presidency, Coolidge came to the 1914 opening of the legislative session with the votes already aligned for an office many thought was going to host an open field.

Taking the podium around noon on that January 7th day, full of ceremony and significance, he delivered a speech that perhaps more than any other defined who he was and how he thought. It was, of course, the “Have Faith in Massachusetts” speech that would later coin the title of the first of three books bringing together some of his best speeches and written messages from a career lasting some thirty years.

The 1914 and 1915 session openings, signaled new beginnings. They were certainly new beginnings for him personally and professionally but new tests and challenges ahead for the people, their representatives, and each state. The interests of one intertwined with the interests of all. They could no more separate from one segment or group in society than a body could dispense with members because it deemed them unworthy or unnecessary. He reminded the legislators assembled before him that day that whatever waited for them around the bend, everyone was in it together. A society of atomistic individuals was complete fiction. It did not exist and to attempt to construct it through legislation would fail. Legislators and the laws they would make could not sever that symbiosis, that intertwining of interests that keeps society inseparable. It had tried with the dramatic flurry of lawmaking in recent years. Legislation could not punish or penalize one demographic without impacting many unforeseen others. The weakest and the strongest did not and could not live in cleanly-sealed vacuums of existence, independent of one another. America had not been built on that fantasy and it could not sustain itself by reconstituting it as such now. To fuel an “us” versus “them” approach to governing always hurt both the members who perpetrated it and those against whom it was attempted.

No law succeeds because people declare it so. Laws are discovered by resting on something eternal, something designed by Heaven not willed by majority vote. This is just as true for courts as it is for legislators. “Courts are established, not to determine the popularity of a cause, but to adjudicate and enforce rights. No litigant should be required to submit his case to the hazard and expense of a political campaign…A hearing means a hearing. When the trial of causes goes outside the court-room…constitutional government ends.”

Legislation cannot and will fail to do it all. But, the prospect of new beginnings Coolidge sought to rekindle that January day one hundred and five years ago, had to begin with faith in the enduring soundness of America’s representative government. Without that faith, a corrosive cynicism would leave nothing but a lifeless shell of what had been a vibrant blessing to millions. It would turn that blessing into a curse. It meant each day had its own work to be done, its own troubles to bear. Seeking to rectify all the injustices of the past neglected the work of the present.

Above all, the daily task of government was spiritual at its core. Eternal things were at stake with each great moment. Material things alone were not at issue. Each decision before the legislator was, at root, a spiritual challenge. Being human is just as indivisible a union of body and soul, spirit and flesh. We can no more live in defiance of this personally than we can as a society. “If it be to protect the rights of the weak, whoever objects, do it. It if be to help a powerful corporation better to serve the people, whatever the opposition, do that.” Coolidge was under no illusions this would make no enemies. On the contrary, “Expect to be called a stand-patter, but don’t be a stand-patter. Expect to be called a demagogue, but don’t be a demagogue. Don’t hesitate to be as revolutionary as science. Don’t hesitate to be as reactionary as the multiplication table.”

But, what should we not expect, President Coolidge? “Don’t expect to build up the weak by pulling down the strong. Don’t hurry to legislate. Give administration a chance to catch up with legislation.”

“We need a broader, firmer, deeper faith in the people…” Consequently, Coolidge closed, “Statutes must appeal to more than material welfare. Wages won’t satisfy, be they never so large. Nor houses; nor lands; nor coupons, though they fall thick as the leaves of autumn. Man has a spiritual nature. Touch it, and it must respond as the magnet responds to the pole. To that, not to selfishness, let the laws…appeal. Recognize the immortal worth and dignity of man…the recognition that all men are peers, the humblest and the most exalted, the recognition that all work is glorified. Such is the path to equality before the law. Such is the foundation of liberty under the law. Such is the sublime revelation of man’s relation to man — Democracy.”

The 1914 Senate took that to heart and President Coolidge could point to a landmark year where legislation substantially decreased while better laws, not merely more of them, were achieved. Quality not quantity prevailed. Self-government was given place to thrive again.

The ivory gavel bestowed to Calvin Coolidge in honor of his inauguration as President of the Senate, 1914.

When the new year rolled around, January 6, 1915, a reelected President Coolidge again took the podium. To him, words were not idle. If leaders are to deserve leadership, the same expectations they preach must be practiced in themselves. Looking to another year of new beginnings, now with the prospect of world war erupting, he spoke:

“My sincere thanks I offer you.” Gratitude led first for Cal as it always did but there was a little bit more to say.

“Conserve the firm foundations of our institutions.” This in 1915 was not a clarion call to prop up the status quo because it was there. It was a challenge to distinguish between the permanent and the ephemeral, the solid and the dubious, the partisan reaction and the principled response. The spiritual import of each choice had not become outmoded or passe. It was the same process he had mentioned the year before: to discover laws not merely make them, to identify the foundations not recklessly protect whatever had been built upon them.

“Do your work with the spirit of a soldier in the public service.” Work again was not only an honorable pursuit, it remained for the legislator to do it whole-heartedly. To adopt sight unseen, measure unread, details unchecked is many things but it is not the work of a legislator. If the office holder is not prepared to do that work, consigning it to “experts” or “advisers,” that person has no place in the role. Again, Coolidge employs the metaphor of battle because there is a metaphysical war constantly unfolding in each legislative hall. Yet, without both discipline and the ability to think for one’s self, directed to nothing higher than the public service, the heart and soul of the work of a legislator goes cold and derelict.

“Be loyal to the commonwealth and to yourselves.” Legislating demands loyalty just as it does for the soldier on the distant field of combat. The enemies may be just as difficult, if not more so, to identify but loyalty is not blindly or lightly given, it is faithfully and soberly bestowed. It does not go to just anyone to be arranged or rescinded with the constant adjustments of political alliances. It goes to the welfare of the whole citizenry, favoring no part of it above the others and in so doing retaining fidelity to one’s own conscience. If the legislator does not acquit the duty entrusted to him or her with care and integrity, forty years of reelections may be assured but it will mean nothing in the scales of eternity. Don’t sell your soul in the process. Don’t become something untrue and lose yourself for transient political advantage. It will all be gone tomorrow and what then will be left of you?

“And be brief; above all things, be brief.” In the shortest inaugural of contemporary memory and perhaps for all time, President Coolidge summarized the essential point – should all else be forgotten – to not forget brevity. Waste in the legislator is the most serious offense. It spends needlessly what is not his or her own. It dilutes the power of good laws. It diverts and misdirects attention and resources to destructive ends or to no purpose at all. It takes all the more time and work from each citizen to restore the damage done. Time is forever lost that could have strengthened wholesome and worthwhile endeavors, which are all the weaker for the waste.

Who would have known that Cal could say so much in forty-two words? Nor is the irony lost on this author that so much space is taken here on behalf of brevity.

Legislation cannot do it all and, even more importantly, should not try. Recognizing the natural limits of legislation, President Coolidge stood at the cusp of new beginnings to declare a sounder path than had been indulged in the opening years of the century. Certain truths had been forgotten along the way that needed to be recognized and restored again. It was not a worship of the past or a reactionary fear of change, it was a reaffirmation of principles that never eclipse but are written into human nature itself. Perspective revealed them but it also reaffirmed that everyone, for all the antagonism of class and caste, remained inseparably in the same boat. Our differences were not so great as to remove our shared humanness. To make every area of life subject to legislative overhaul, attempting to separate “your” interests from “my” interests on seemingly limitless fronts, had not only brought everyone to no good destination, it had proved far worse than the most optimistic imagined, a false and illusory path of terrible consequences for everyone. To insist on that former path works in defiance of eternal truths no one can overturn.

Coolidge pointed to a better way. It was not built on his own wisdom or glory but on the humble realization that we, like the human body itself, need all its members working in their different roles to advance the life and health of the whole. Though each works differently, the interests of all, being inexorably bound together, cannot survive severed from the rest. They are all enveloped by that intangible and seamless union of spirit and soul with the body which makes us unavoidably more than material beings. Our choices are much more than so many material effects but spiritual in dimension and eternal in reach. We can no more survive by indulging warfare among the members of our own body than we can in the political body of which we are all parts. It was thus why Coolidge took both occasions in 1914 and again 1915 to underscore the higher cause we serve when we take up the work of legislation.

Walk circumspectly then, dear legislators, in this coming year. Acquit your trust so faithfully that you will be able to know the freedom of a clean conscience when your work is done. Have the discipline to do all the work it requires. Avoid waste like it were a pestilence. Keep your words few and to the point. Master yourself first or you will not be fit to lead others. You may deceive voters for a time, but you will never escape the knowledge of a wrong done in secret. Know that you face spiritual battles ahead not merely political ones so armor up accordingly. Let what laws seeking your name and reputation reflect that same clarity of expression and clarity of purpose. Have the courage to withhold your vote when bills and resolutions fail to earn that clarity. Be loyal to the whole body of citizens you represent and to yourself. Rise to be worthy of the trust placed in you. You can go far but you never get away from a trust once broken. Take what President Coolidge urges you as a challenge to see if you really do measure up to the office you currently hold (not the one you aspire to next!). Begin anew, at this moment, whether or not you have practiced any of this up to now. The next hour may be forever too late. And remember, “be brief; above all things, be brief.”

The typed text of Coolidge’s second inaugural as President of the Senate, 1915. An interesting note in shorthand on the upper right compliments the speech. Photo credit: State Library of Massachusetts.