At first glance, there do not appear to be many similarities between Calvin Coolidge and Harry Truman. Coolidge would never be heard uttering the kind of salty language Truman frequently employed. Coolidge knew how to be crisp and to the point without the colorful metaphors. Both had a strong sense of the Presidential Office’s duty, however, and guarded fiercely his own moral integrity. Aside from the obvious differences of party and regional upbringing, they both came from the country. Even so, 1923 and 1945 (the years they ascended to the White House) were about as different as any separate worlds can be despite being a mere twenty-two years apart. Both men succeeded following the deaths of their predecessors and would win elections in their own right, the 1924 three-way contest remaining the more decisive of the two. They would both lead into a post-war world, facing the challenges and uncertainty of returning to peacetime. War broke out again under Truman while Coolidge kept the peace. They both used the veto and executive power in decisive ways, neither without controversy. For both of them, the “buck stopped at the President’s desk.” They did things differently, to be sure, possessing distinct styles of executive administration, but both could be as immovable as granite when duty required. They would both preside over significant reconstruction projects of the people’s White House, the introduction of a steel-beamed third floor in 1927 and the 1949-1952 renovation, which remains the most substantial work done since the mansion’s burning in 1814. Both were efforts to correct the unfortunate installation in 1902 of a second floor truss and its subsequent strain on the overall structure.

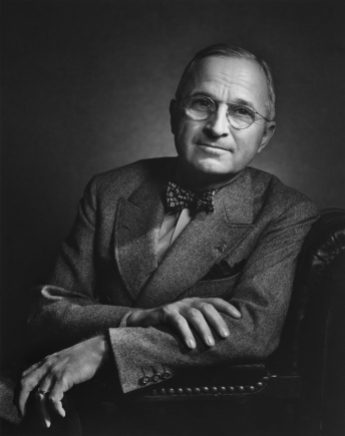

Though Coolidge and Truman apparently never met, they were being prepared for national leadership in different ways at the same time. Truman served as an artilleryman during the Great War and then ventured into haberdashery (his shop being hit by the 1921 depression) and then served as county judge before reaching the U.S. Senate while Coolidge was war-time governor of Massachusetts and then Vice President. Truman would enjoy a much longer post-presidency and yet both returned to the people from whom they came, quiet ‘Main Street’ America. While Coolidge left office adored by the people, it has been intellectuals who join in a chorus of hostility toward Cal while reserving accolades for Harry. Both were more alike than such academics usually countenance. Though, on the campaign trail, Truman helped echo this critical chord as a partisan candidate, I think even Harry learned to walk with greater perspective and a higher regard for his predecessors once he had also been there. They both knew the country could do just fine after their season of leadership had passed to others. They did not see themselves in any sense as indispensable forces. They were above all, thoroughly and authentically human. In one of those frequent points in history when only two former Presidents lived contemporaneously, the years 1924-1930 and 1945-1961 resemble each other. Truman would have the benefit of Hoover’s experience just as Coolidge had had from Taft before them. I think Harry now would find this animus against Coolidge has been unfair to #30 and be rightly repulsed by it. If nothing more, his sense of justice would find it intolerable. Not only this but, as his daughter once noted, Truman was an avid collector of Coolidge stories. He loved them. They were hilarious. They taught while they made you laugh.

Harry’s favorite was the old story about one of those mystifying pancake breakfasts Coolidge often held for legislators. The legislators never quite caught on to the rationale behind these breakfasts, failing to detect that Cal was taking his measure of them, sizing them up and seeing how they reacted, what made them tick, how they thought, how they worked and how they handled situations. Harry relished hearing and recounting the old instance when one of those legislators, Texas Senator Morris Sheppard, sat at table with a piece of bacon still lingering on his plate while Rob Roy, the ever-observant white collie, stared eagerly up at him. “He wants your bacon,” Cal cracked to Sheppard. The unsuspecting Sheppard gave it away and no new slice was forthcoming for the cajoled, but now baconless, Senator from Texas. In Aesop-like fashion: He gave too freely under pressure and illustrated that cautionary tale of legislators snookered by the lobbyist, even when it turns out that lobbyist is a dog.

Pingback: Coolidge in Jared Cohen’s “Accidental Presidents: Eight Men Who Changed America” | The Importance of the Obvious