Aerial view of Midtown Manhattan, May 1925. The Plaza Hotel is in the foreground. The Empire State Building would not be constructed until 1931.

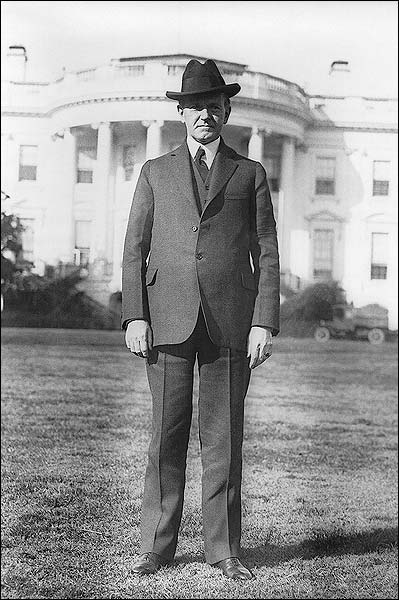

When Calvin Coolidge accepted the invitation to address the Chamber of Commerce of the State of New York on November 19, 1925, he would speak to the oldest collaboration of entrepreneurs, merchants and businessmen in America. This Chamber, after all, preceded the Declaration of Independence by eight years. Coolidge came to the bustling hub of the nation’s commerce to stand before some of the most accomplished leaders of the marketplace. Not intimidated by either their presence or reputations, Coolidge was caught by the awe and admiration he felt for what New York represented: “the genius of the American spirit.” He observed, “We are met not only in the greatest American metropolis, but in the greater center of population and business that the world has ever known. If any one wishes to gauge the power which is represented by the genius of the American spirit, let him contemplate the wonders which have been wrought in this region in the short space of 200 years. Not only does it stand unequaled by any other place on earth, but it is impossible to conceive of any other place where it could be equaled.” It was all due to the exceptionalism of America’s design, Coolidge would go on to declare. It was no accident that economic freedom could achieve such heights. Such was inherent in recognizing and protecting the opportunity of each individual.

Whereas ancient empires had consolidated political and economic controls into one central government, America was different. New York was still “an imperial city, but it is not a seat of government. The empire over which it rules is not political, but commercial.” This separation was not only deliberate but wise to maintain, Coolidge continued. It was right that, especially in New York City, the government remain merely one tenant among many, not an authoritarian landlord.

He likened Washington and New York City to free-flowing streams which run parallel to one another without ever joining. Had that clear separation never been made, however, the results would have been disastrous not only for New York but for the commerce of the entire country. “When we contemplate the enormous power, autocratic and uncontrolled, which would have been created by joining the authority of government with the influence of business, we can better appreciate the wisdom of the fathers in their wise dispensation which made Washington the political center of the country and left New York to develop into its business center. They wrought mightily for freedom.” The opposite holds equally true today. When government grows, individual opportunity shrinks in proportion to it. For Coolidge, the advantages of keeping business separate from government were easily apparent and readily justified.

What was lacking between the economic world and the political world was not greater supervision but greater understanding between them. While Coolidge could accurately assert that were any contest to take place between the knowledge of business by government and government by business, government officials would win. Considering the profound experience of administration leaders like Andrew Mellon and S. Parker Gilbert at Treasury, Charles Evans Hughes at State and Herbert Lord at the Budget Bureau, including many others with backgrounds in monetary and commercial fields, Coolidge was not exaggerating. Back then, there were highly capable businessmen in government, not to obtain favors for cronies but to serve for the good of the entire country. These were men who understand both worlds and yet even they knew their personal and constitutional limits and respected them.

Coolidge then said, the “general welfare of our country could be very much advanced through a better knowledge by both of those parties of the multifold problems with which each has to deal.” Even so, Coolidge explained, “I should put an even stronger emphasis on the desirability of the largest possible independence between government and business. Each ought to be sovereign in its own sphere.” Washington was not be lord and master subjugating commerce to each bureaucratic whim. The throne of commerce was not to be usurped and co-opted by political power. Likewise, governance for the welfare of all was not salable to the ambitions of business interests.

The outcome, when either authority is supplanted, was clearly abhorrent to Coolidge. “When government comes unduly under the influence of business, the tendency is to develop an administration which closes the door of opportunity; becomes narrow and selfish in its outlook, and results in an oligarchy.” This is what makes the charge ring hollow that Coolidge blindly served “Big Business” at the expense of the country as a whole. Individual opportunity is measured in several ways but by every standard — from unemployment rates of 3.8 per cent to 4.5 per cent annual growth to any number of consumption statistics — the door of opportunity was wider than it had ever been before thanks to an unwavering commitment to keep limited government and commercial freedom separate. Coolidge did not stop there, noting the other “side of the coin,” “When government enters the field of business with its great resources, it has a tendency to extravagance and inefficiency, but, having the power to crush all competitors, likewise closes the door of opportunity and results in monopoly.” Through a “reasonable vigilance” by the people to “preserve their freedom” the threat was not serious then and can be thwarted now.

As Coolidge stood before Chamber President Ecker and those comprising the organization, he took the occasion to define what he meant by “business.” His exposition should put an end to the long-cherished claim that he “worshiped ‘Big Business’ ” (i.e., rich corporations) at the expense of the “little guy” (the small business operator, the single entrepreneur or the blue-collar worker). On the contrary, to Coolidge, business meant everything Americans do. He did not see a series of groups in conflict: labor versus capital, industry versus agriculture, creditor versus debtor. Instead he saw a symbiotic collaboration made possible when opportunity is maximized, where all serve and are served.

He said, “I have used the word in its all-inclusive sense to denote alike the employer and employee, the production of agriculture and industry, the distribution of transportation and commerce, and the service of finance and banking. It is the work of the world.” Capitalism was not institutionalized selfishness; “it rests on a higher law. True business represents the mutual organized effort of society to minister to the economic requirements of civilization. It is an effort by which men provide for the material needs of each other. While it is not an end in itself, it is the important means for the attainment of a supreme end. It rests squarely on the law of service. It has for its main reliance truth and faith and justice.”

Those gathered in downtown Manhattan that day could have expected Coolidge to roll out grand assurances of preferential treatment by his Administration. Perhaps some of those present thought he would validate an unqualified laissez-faire policy, where government would, with a wink and nod, ignore any future abuses by corporations. They would both be disappointed. Coolidge ventured into the controversial territory of the purpose for government involvement in business. He rejected the “autocratic practice abroad of directly supporting and financing business projects.” The socialist approach where government subsidized particular entities it favored would have no place here in normal, every day America. Solyndra would have never obtained a dime under Coolidge. Stimulus appropriations, especially those benefiting winners and losers based on political alliances, would have been a betrayal of government’s proper purpose.

The emergency of the moment did not preclude the rule that America was to nurture free markets. Coolidge laid out his policy, “we have rather held to a democratic policy of cherishing the general structure of business while holding its avenues open to the widest competition, in order that its opportunities and its benefits might be given the broadest possible participation.” To Coolidge, government was not nor should it be participant in the “game.” Government was to encourage an environment of friendliness, not hostility, to the fullest involvement of everyone, letting the market decide success and failure. The government, enforcing the law to prevent monopolies and place standards of regulation on transportation and trade was not to assume powers belonging to business, it was “to have business remain business. We are politically free people and must be an economically free people.” The welfare of all the people is given to the national government, not to an independent commission or trade association. Government cannot farm out that responsibility if opportunity for everyone is to be maximized.

Coolidge was no blind believer in government power, as he made plain next, “It is notorious that where the government is bad, business is bad.” The protection of property and the enforcement of lawful order is government’s first and most essential contribution to business. Even these necessary functions have been misapplied and “run into excesses…Regulation has often become restriction, and inspection has too frequently been little less than obstruction.”

Recalling the experiences of the recent past, Coolidge noted that long after informed public opinion corrected the abuses by those taking advantage of economic freedom to abuse others, an unwarranted prejudice remained. That widespread public prejudice becoming enshrined in legislation ended up doing far more harm than good to economic opportunity. “It is this misconception and misapplication, disturbing and wasteful in their results, which the National Government is attempting to avoid.” Coolidge neither nursed a prejudice against business to conscientiously correct abuses nor did he subscribe to an unquestioned confidence in government to right all wrongs.

The lesson of history was not to grasp for greater regulatory countermeasures but to keep faith in the American people, who corrected the abuses without legislation in the past and could be trusted to do so with continued vigilance into the future. The answer was not to be found by looking to government to “fix” business. The answer is found in the public upholding common standards for just dealing.

Seeing the return of prosperity and unprecedented expansion of opportunity, Coolidge seized the occasion to enumerate the additional ways government reinforces business. First, a policy of economy provides the “only method of regeneration.” Pairing tax reduction and protective tariff rates releases pent-up capital and gives production the incentive to produce. Second, a policy pursuing the elimination of waste in the use of resources protects the “smaller units of business,” the producer, the wage earner and the consumer. The previous five years, Coolidge praised, could lay claim to many successes on the part of business allowed to find solutions, instead of government mandating actions. By offering a cooperative environment in which to work, government fostered freer business.

The regulation of corporations twenty years before had served its purpose, now this shift for government and business was no less important. The collaboration underway was producing a real and solid progress. One need only see the improvement of living standards, the increase in affluence and the free movement of capital to perceive its success. This was not all, however. Debt was liquidating while taxes were coming down. Wages were actually going up while prices were actually coming down. These were results everyone could see. “The wage earner receives more, while the dollar of the consumer will purchase more,” Coolidge told the Chamber. “It must be maintained” because more work remained to be done. Business still had much to do and government needed to keep policy consistent so progress continued.

All of these advancements were not merely the simple give and take of a market transaction. They contained great moral and spiritual implications, not only for America but for the rest of the world. America had just saved Europe from “complete collapse,” Coolidge reminded his audience. “It ought everywhere to be welcomed with rejoicing and considered as a part of the good fortune of the entire world that such an economic reservoir exists here which can be made available in case of need.” Government economy then pertains as much to foreign policy as to domestic good. It was no less imperative in the settling of foreign war debts. “Peace,” Coolidge would say, “rests to a great extent upon justice, but it is very difficult for the public mind to divorce justice from economic opportunity.” Our political affairs cannot attain righteous ends without preserving the freedom of the marketplace.

As Coolidge neared the close of his remarks, he urged his listeners of the great expectations placed on America, within man’s work in this world. “The working out of these problems of regulation, Government economy, the elimination of waste in the use of man effort and materials, conservation and the proper investment of our savings both at home and abroad, is all a part of the mighty task which was imposed upon mankind of subduing the earth. America must either perform her full share in the accomplishment of this great world destiny or fail.”

Then Coolidge pressed the point home that all of our efforts, all of our relations must rest on “a system of law.” It is upon law, the reasonable and orderly appeal to higher standards that success will continue. Reflecting on George Washington, President Coolidge derived his closing inspiration in what the future held. As Washington did, “[w]e must meet our perils; we must encounter our dangers; we must make our sacrifices, or history will recount that the works of [George] Washington have failed. I do not believe the future is to be dismayed by that record. The truth and faith and justice of the ancient days have not departed from us.”