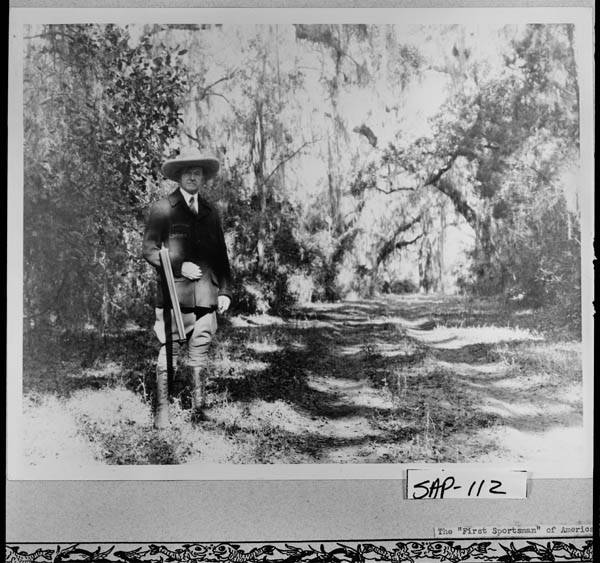

President Coolidge, dubbed here “The ‘First Sportsman’ of America,” pausing before his quail hunt in the scrub of Sapelo Island, Georgia.

President Coolidge, dubbed here “The ‘First Sportsman’ of America,” pausing before his quail hunt in the scrub of Sapelo Island, Georgia.

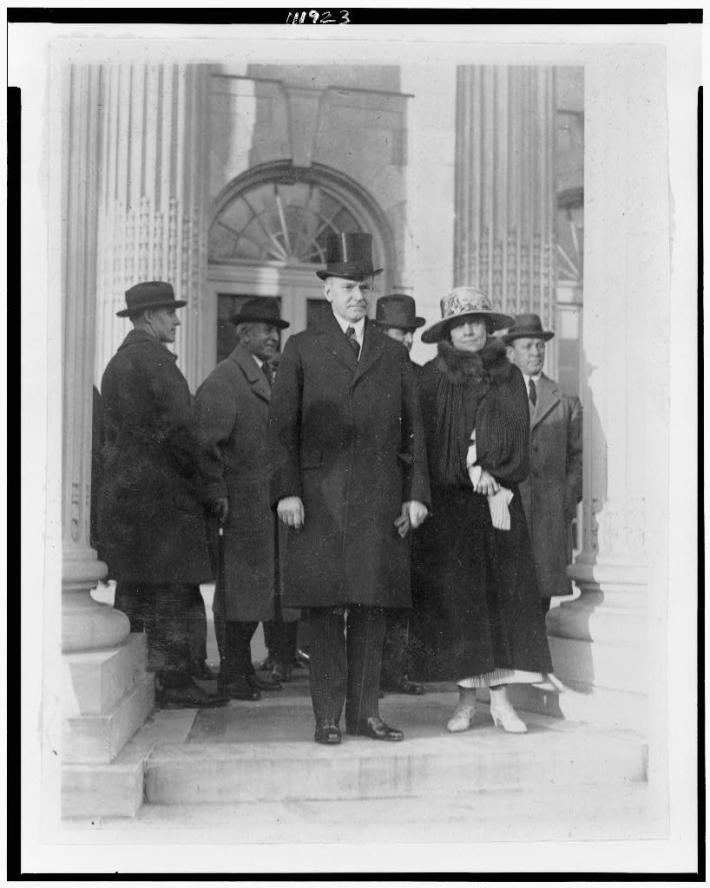

President and Mrs. Coolidge arrive at the train station in Brunswick, Georgia, before heading out to Sapelo Island. Courtesy of the Georgia Archives.

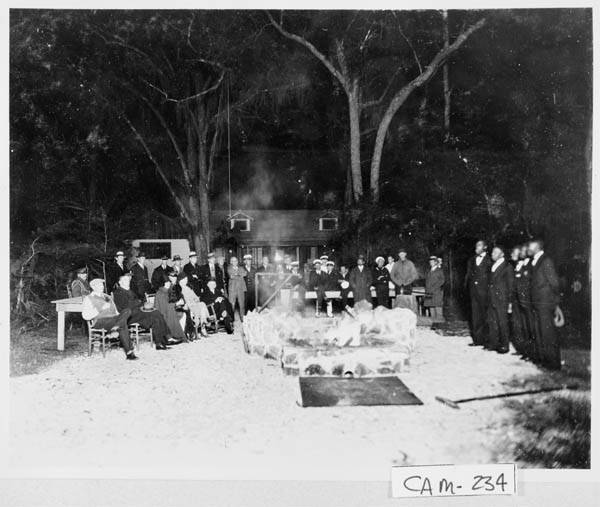

The Coolidges at Cabin Bluff enjoying an old-fashioned oyster roast around the fire. The President and Mrs. Coolidge are seated in the front row on the left (Grace is third from left, Calvin sits on the far right end). Courtesy of the Georgia Archives.

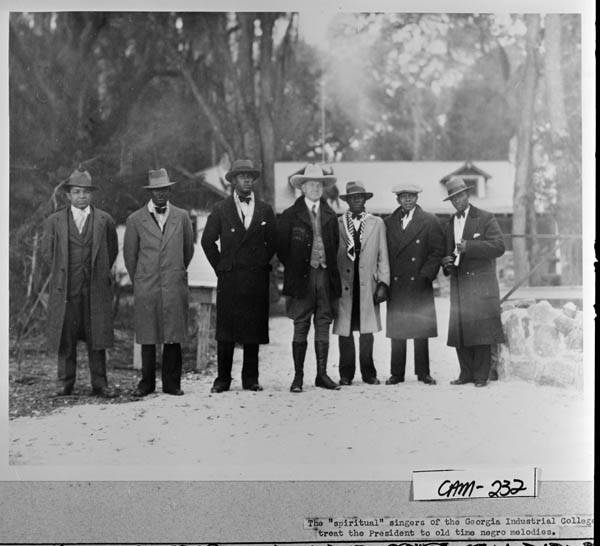

President Coolidge at Cabin Bluff with the “spiritual” singers of Georgia Industrial College. Courtesy of the Georgia Archives.

The Coolidges visit the Sugar House ruins, St Marys, belonging to John H. McIntosh. Notice the tabby oyster shells used commonly along the Virginia, Carolina, Georgia and Florida coasts as a building material. These were thought to be the ruins of the old Spanish mission of Santa Maria. Courtesy of the Georgia Archives.

Crowds gathered to see the First Lady at a reception in her honor, St Marys dock. Courtesy of the Georgia Archives.

President and Mrs. Coolidge welcomed by their hosts, Mr. and Mrs. Howard E. Coffin, at the Sea Island Yacht Club. Courtesy of the Georgia Archives.

At Sea Island, December 1928, Coolidge planted “The Constitution Oak” on the grounds of newly constructed Spanish Revival style hotel, The Cloister, designed by Addison Mizner and owned by Howard E. Coffin and his wife (pictured here beside Grace Coolidge). Courtesy of the Georgia Archives.

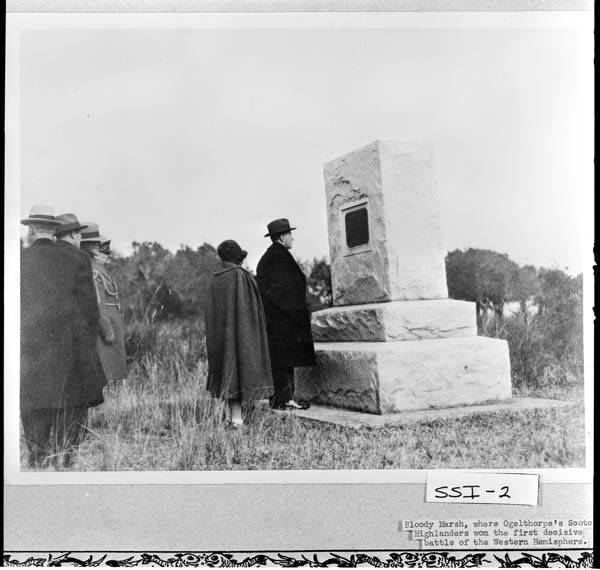

The Coolidges visiting the Monument to the Battle of Bloody Marsh, July 7, 1742, when the Spanish attacked Georgia held by the British, under General James Oglethorpe, whose Scottish Highlanders soundly defeated the Spaniards in what proved to be the first decisive engagement in the Western Hemisphere. General Oglethorpe redeemed his reputation after the defeat at St. Augustine two years before. It would set America further down the road on her course to independence. Courtesy of the Georgia Archives.

President Coolidge watches the steer riding along the beaches of Sapelo Island, December 1928. Courtesy of the Georgia Archives.

Coolidge and Mr. Coffin happen upon some sea turtles on the beach, Sapelo Island. Courtesy of the Georgia Archives.

President Coolidge, unsuccessful at quail, and military aide Colonel Latrobe, proudly display the pheasants shot during their hunt, Sapelo Island. Courtesy of the Georgia Archives.

The motor yacht Zapala sails with the Presidential party aboard. Note the President’s flag is raised. Courtesy of the Georgia Archives.

President Coolidge and another man, perhaps Secret Service, standing on the afterdeck of the Zapala. Courtesy of Mystic Seaport and Connecticut History Online.

The Coolidges on the afterdeck of the Zapala, the yacht designed by A. E. Luders and built in Stamford, CT, in 1927. Courtesy of Mystic Seaport and Connecticut History Online.

The Presidential hunting party disembarks from the Zapala, which would consider Georgia its home base for fourteen years, 1927-1941. Courtesy of the Georgia Archives.

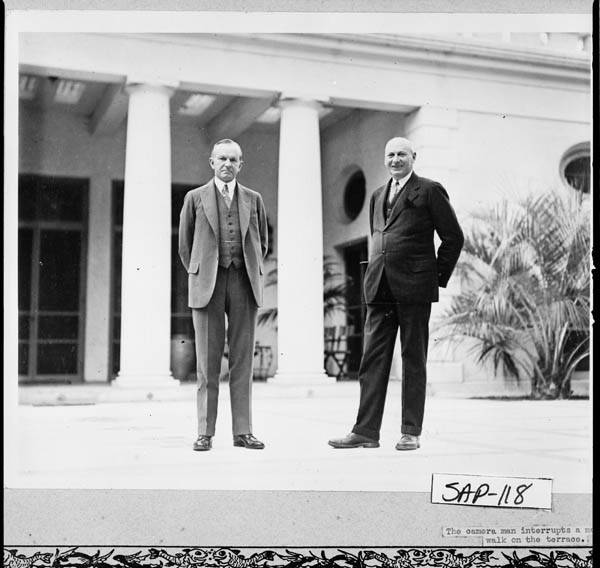

Calvin Coolidge and his friend and host, entrepreneur Howard E. Coffin, as they walk the terrace of “The Big House” built by Thomas Spalding, 1810, Sapelo Island. Courtesy of the Georgia Archives.

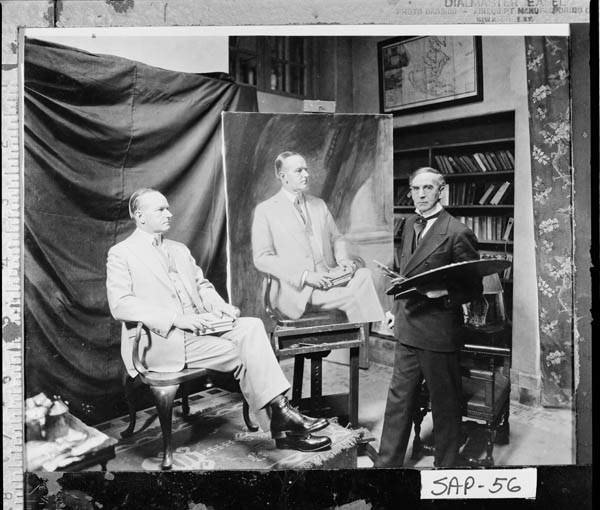

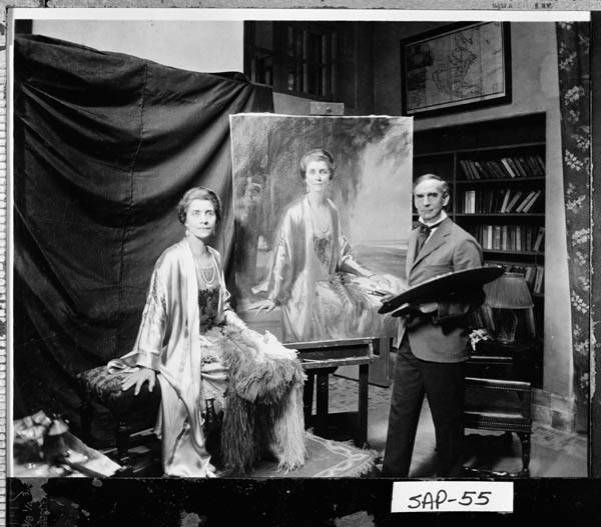

It was also during their stay, as we have mentioned before, that the Coolidges both sat for British painter Frank O. Salisbury at “The Big House” on Sapelo Island. Salisbury would be commissioned again in 1934, following Mr. Coolidge’s death, to produce another portrait for the American Antiquarian Society. Mr. Salisbury, at that time, painted Coolidge in a dark suit with strikingly similar pose to the original work seen above six years earlier.

It was also during their stay, as we have mentioned before, that the Coolidges both sat for British painter Frank O. Salisbury at “The Big House” on Sapelo Island. Salisbury would be commissioned again in 1934, following Mr. Coolidge’s death, to produce another portrait for the American Antiquarian Society. Mr. Salisbury, at that time, painted Coolidge in a dark suit with strikingly similar pose to the original work seen above six years earlier.