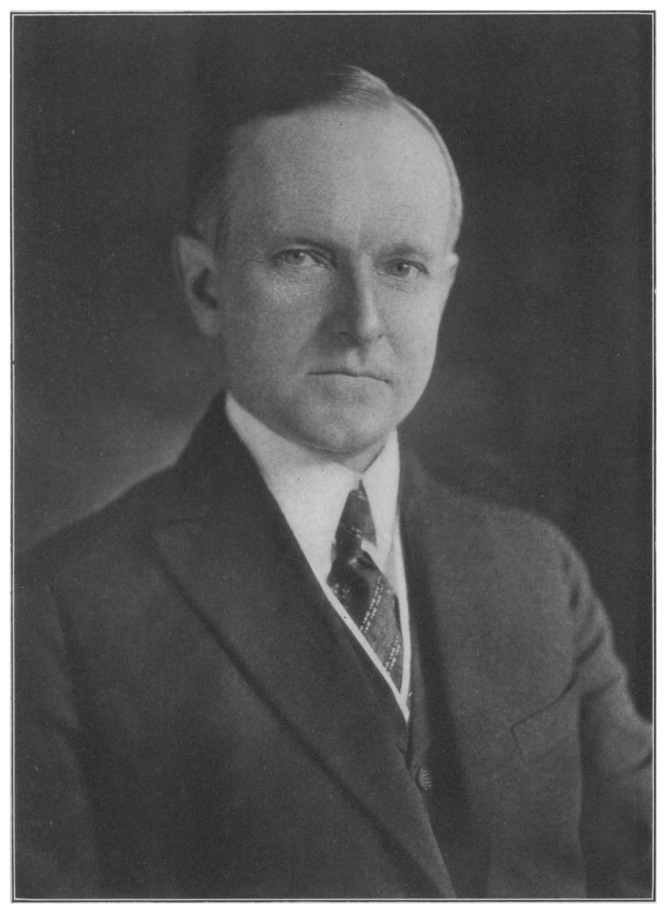

“America has so many elements of greatness that it is difficult to decide which is the most important. It is probable that a careful consideration would reveal that the progress of civilization is so much a matter of interdependence that we could not dispense with any of them without great sacrifice…[O]ne of the most important factors of our everyday existence is the public health, which has come to be dependent upon sanitation and the medical profession…This great work is carried on partly through private initiative, partly through Government effort, partly by a combination of these two working in harmony with the science of chemistry, of engineering, and of applied medicine. In its main aspects it is preventive, but in a very large field it is remedial. Without this service our large centers of population would be overwhelmed and dissipated almost in a day and the modern organization of society would be altogether destroyed. The debt which we owe to the science of medicine is simply beyond computation or comprehension…

Poster in front of a Chicago theater in 1918. Most Americans remembered that dreadful outbreak as the American Medical Association met in May 1927 for its 78th Annual Session in Washington. They knew it was the courageous doctors and nurses throughout the country who treated the sick, helped whom they could and prevented many more deaths at great personal risk.

“…Although great progress has been made and certain fundamental rules have become well established, we can not yet estimate the development of scientific research as much more than begun. But great effort is being put out all around us and a constant advancement of knowledge is in progress. This has been especially true in the science of medicine. Many of the diseases which laid a heavy toll on life have been entirely eradicated and many others have been greatly circumscribed. The average length of life has been much increased…

“…If there is any one thing which the progress of science has taught us, it is the necessity of an open mind. Without this attitude very little advancement could be made. Truth must always be able to demonstrate itself. But when it has been demonstrated, in whatsoever direction it may lead, it ought to be followed. The remarkable ability of America to adopt this policy has been one of the leading factors in its rise to power. When a principle has been demonstrated, the American people have not hesitated to adopt it and put it into practice. Being free from the unwarranted impediments of custom and caste, we have been able to accept whole-heartedly the results of research and investigation and the benefits of discovery and invention.

“This policy has been the practical working out of the applied theory of efficiency in life. We have opened our mines and assembled coal and iron with which we have wrought wonderful machinery, we have harnessed our water power, we have directed invention to agriculture, the result of which has been to put more power at the disposal of the individual, eliminating waste and increasing production. It has all been a coordination of effort, which has raised the whole standard of life.

John A. Andrew Hospital, the well-known Tuskegee Veterans medical facility, directed by Dr. John A. Kenney, Jr. a leading specialist in dermatology research. It would be none other than President Coolidge who defended the black leadership of that institution and helped ensure proper care was given to all those who came to it. Coolidge did not abide racial preferences on any front, but was especially involved in the controversy at Tuskegee over race and the progress of medicine there.

“In the development of this general policy the science of medicine has had its part to play…We are practicing economy in our governmental affairs. But the conservation of human health and life is one of the greatest achievements in the advance of civilization, both socially and economically.

“What an incalculable loss to the world may have been the premature blotting out of a single brilliant creative mind which might have been saved through modern healing or preventive measures.” A policy which subordinates the precious potential of an individual’s life to inefficient and wasteful procedures is a repudiation of civilization. Coolidge makes clear who is responsible for such continual advancements in medicine, looking back to a time before “medical men,” without the involvement of bureaucrats, removed diseases “of their terrors,” when once “a single case of yellow fever or cholera reported in New York Harbor caused such panic as seriously to interfere with business. Now such sporadic cases would scarcely cause public comment…There is no finer page in the history of civilization than that which records the advance of medical science. The heroism of those who have worked with deadly germs and permitted themselves to be inoculated with disease, to the end that countless thousands might be saved, was less spectacular but no less far-reaching than that on the battle field or of an isolated rescue from a burning building or a sinking ship.”

Influenza took the lives of 6 million people in 1918. Those who survived remembered how devastating the loss was, especially just as the War came to a halt. It was also remembered that government-operated military bases were the first and most severe hit. Coolidge, like most in the audience in May of 1927, knew that government’s tendency to place political considerations in the administration of healthcare was not a viable model or safe solution for the future.

It was hardly coincidental that not only had average lifespans tripled since the early 19th century but “most of that gain has been made in the past half century” through the increase of knowledge and personal initiative by practitioners and patients. Of course, government at all levels had become aware of the “public functions” entailed in preserving health and conserving life, as “[n]o more striking achievement was ever accomplished than by Doctor Gorgas, of the United States Army, in cleaning up the Panama Canal Zone. Under French control, the death rate in that area was 240 per thousand. In 1913 it had dropped to 8.35 per thousand. Without this work the construction and operation of the canal would have been impossible.” Yet, government does not maintain health, it can only help the institutions which do, the individual and the doctor.

For medical advances to continue in the universities and growing number of hospitals around the country, physicians and nurses would have to be allowed to continue their work freed of regulatory and administrative constraints to apply new findings and best procedures for the good of the patient. Free markets had and would continue to furnish results. The affordability of health insurance would continue to spread, so that Coolidge could proudly observe that “[n]ot a few individuals” could retain the physicians they chose to provide personal care all year around. The steadfast and formal opposition to mandatory health insurance by the very group of medical professionals President Coolidge addressed was not a roadblock to progress, it was a means to conserve and expand sustainable and proficient care for as many people as wished to make use of it. A sound future remained in this direction. “The modern broad-minded physician…willing to use or to recommend whatever methods seem best suited to the case in hand” had to be encouraged not shackled by the red-tape of administration. It is the physician — not government — who is “the strongest advocate of prevention.” Bureaucrats, known for prioritizing political considerations above real-time initiative and medical innovation, simply do not possess the competence or skill necessary to supplant those closest to the situation, even in the best of times.

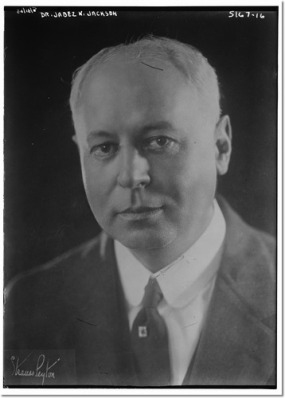

Dr. Jabez N. Jackson led the American Medical Association and its Annual proceedings as Coolidge came to visit, May 1927.

Mordecai Johnson, the new President of Howard University in 1926, would cultivate and develop a medical school that would lead research and medical knowledge in the years to come. Bringing on Amherst graduate (class of 1926) Dr. Charles R. Drew would prove an immeasurable contribution to medical advancement, especially in the field of blood transfusion. Coolidge was a faithful advocate for the University and helped build up its medical program.

Dr. Charles R. Drew

The roar of economic growth during the 1920s contributed tremendously to the breadth and inclusiveness of opportunities, not merely economic and professional but in the health of Americans. Coolidge could report with the full awareness of so illustrious an assembly of medical people as present that night that “the great body of our population is able to secure adequate medical attention.” How was this possible? This was long before the New Deal, the Great Society or “Obamacare.” He was not exaggerating, however, as the more than 6,200 attendees knew. The audience filling a packed auditorium that day comprised members of the American Medical Association, an organization representing 94,000 of the 140,000 physicians in the country at that time. They knew he was right. “This is true,” Coolidge declared, “to a remarkable degree of all our great centers of population,” with only the remotest quarters unable to provide such service, a fact which was itself changing with better roads and Ford’s automobile. The larger cities could furnish “free dispensaries” and “free service” thanks to the unsparing dedication of “time and…skill” physicians were already giving “for the alleviation of human suffering.” America’s “private benefactors,” “organized charities” and “governmental agencies” may contribute support and encouragement “to this most important purpose” but it is to those directly concerned, the skilled medical men and women of this country and their patients, who make it possible.

“This is an enormous contribution…to human welfare. It is one of the undeniable evidences of the soundness and success of American institutions. The fact that our attainments and our blessings have become common is no reason why they should be ignored.” As the Annual Session of 1927 would come to a close three days later, President Coolidge would launch a Committee on the Costs of Medical Care to study the intricate problems and propose solutions for making care even more attainable, lowering its costs while increasing its access. The forty-eight medical professionals, administrators and economists appointed to the Committee would meet regularly for five years, submitting numerous reports and concluding their research with a final study on the issue in 1932. Among the recommendations fought for and approved by the AMA since 1920 remained a commitment to voluntary health insurance and an individual’s choice of care.

In fact, the only way Roosevelt’s Social Security Act passed in 1935 was contingent on the stipulation insisted by the Association that health insurance remain a matter left up to individuals. The Association would continue championing freedom of choice against Truman’s plan to socialize medicine in 1948 and the practice of fee splitting in 1952, an activity that would only escalate costs and create more middlemen that further separates a patient from obtaining only the care for which one chooses to pay.

Yet, with much of this still future, President Coolidge stood before the thousands gathered in Washington that evening of May 17, 1927, to close with some timeless observations on where the future of medicine turned if it were to remain sound and solvent. We could sit back and criticize the deficiencies of our free market system and the shortcomings of medical care or we could remember how far we have come because of that freedom to innovate, improve and serve. “Mere fault finding has no value except to reveal the poverty of the intellect which constantly engages in it,” Coolidge proclaimed. “Our country, our Government, our state of society, are a long way from being perfect, but the fact that our structure is not complete is no reason for refusing to assess at their proper value the usefulness and beauty of those parts which are nearing completion, or withholding our approval from the general plan of construction and neglecting to join in the common effort to carry on the work.”

Medical professionals gathered in Washington for the 1927 AMA Session gather here to honor the 500 doctors who died while at their work during World War I, Arlington Amphitheater, May 17, 1927.

Humanity can no longer live under the excuse of insufficient experience. “It has located a great many fixed stars in the firmament of truth. No doubt a multitude of others await the revelation of a more extended research. But because we realize that we have not yet located them all is no reason for doubting the existence of those already observed or disregarding the records which reveal their position. To engage in such a course would lead to nothing but disaster.” By rejecting the markers of history, presuming to “reinvent the wheel” of human nature along failed and close-minded lines of experience, our current crop of leaders in Washington is beckoning that very disaster Coolidge foresaw.

The problem is not one of knowledge, Coolidge reminds us, but an unwillingness “to live in accordance with the knowledge which we have.” Coolidge elaborated, “Approbation of the Ten Commandments is almost universal. The principles they declare are sanctioned by the common consent of mankind. We do not lack in knowledge of them. We lack in ability to live by them.” Medical knowledge will continue to increase but it cannot advance us beyond moral knowledge with its obligations. The “structural weakness” we see is not in the foundations of American liberties, it resides “[s]omewhere in human nature” itself. “We do not do as well as we know. We make many constitutions, we enact many laws, laying out a course of action and providing a method of relationship one with another which are theoretically above criticism, but they do not come into full observance and effect.” Crime and war continue with us, even with what is, as Coolidge affirmed on another occasion, “the greatest political privilege that was ever accorded to the human race” by living under the American Constitution. The standard of freedom is not flawed, we are, as human beings.

Gathered to honor the memory of the American who discovered in 1842 the aesthetic properties in surgery of sulphuric ether, Dr. Thomas A. Grooner, Dr. Charles H. Mayo and the daughter of Dr. Long, visit the statue of Dr. Crawford Long, native of Georgia, May 16, 1927.

The future soundness of medicine rests not in greater restrictions on individual responsibility over health, the rationing of care along political factors, the replacement of medical competence with bureaucratic oversight or the increasing reach and revenue of third parties in the process but remains among those “fixed stars” discovered by America’s balance of liberty with self-government and personal prevention. The solutions are found in maximizing a patient’s range of choices, supporting not tying the able hands or closing the open-minds of those who directly provide care, while reaffirming the sanctity of an individual’s life.

President Coolidge with his predecessor’s physician, General Sawyer and Passed Assistant Surgeon Joel T. Boone, who became a Coolidge family close friend and their primary doctor during the 1920s. Boone’s medical judgment was exceptional and the loss of President Harding, the timely rescue of Mrs. Harding’s life and the death of Calvin Jr. weighed heavily on him, despite doing all that the best medical expertise could do in each case. Boone was a sound physician and a strong example of medical heroism.

The Hippocratic standard “Never do harm to anyone” means more than a thousand decrees from Washington because it finds validation in the fundamental precepts of the Ten Commandments. Many “of our social problems” have physical causes but that is not the final word on the matter. Our problems go deeper than the physical symptoms. “If we could effectively rid our systems of poison, not only would our bodily vigor be strengthened, but our vision would be clearer, our judgment more accurate, and our moral power increased. We should come to a more perfect appreciation of the truth.” Coolidge maintained, “It is to your profession in its broadest sense untrammeled by the contentions of different schools,” not to mention administrative boards and political planners, “that the world may look for large contributions toward its regeneration, physically, mentally, and spiritually, when not force but reason will hold universal sway.”

President Coolidge was not pronouncing some all-encompassing faith in either a “Church of Medicine” or a Great Collective State, but was appealing to something far more profound, more ancient and eternally important. The future soundness of medicine remained where it always has — with the free will, ability and moral power of the individual, who administers care to the whole person not through coercion but through what one gives willingly in service to others according to the patient’s ability to pay. The fullest provision of treating mind, body and soul will never be actualized via statute or administrative ordinance. Only we can make that happen. Strengthening the partnership between patients and their doctors realizes the freedom of contract inherent in our system. It smooths the path to medical — and spiritual — progress. Or, as Coolidge put it, “As human beings gain in individual perfection, so the world will gain in social perfection, and we may hope to come into an era of right living and right thinking, of good will, and of peace, in accordance with the teachings of the Great Physician.”

Overruling his own doctor, President Coolidge ventures out in the rain to greet the thousands of doctors gathered at the White House the day after his speech to these professionals in Washington for the American Medical Association’s Annual Session, May 18, 1927.