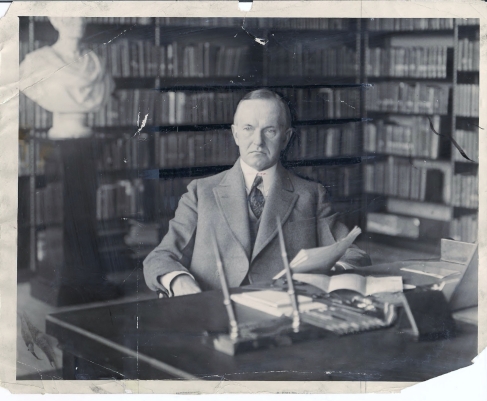

President Coolidge took nearly everyone by surprise when he mounted the podium on the floor of Congress, December 6, 1923, for his first major Presidential address, the first of six annual messages. The “silent” former Vice President enjoyed being underestimated, especially by the “experts,” and when an occasion presented to reveal their erroneous judgment, he took it. This “provincial” man set the tone for where he was going to lead in the future, bravely beginning with foreign policy. He explained the general principles before dealing in specifics,

“Our country has one cardinal principle to maintain in its foreign policy. It is an American principle. It must be an American policy. We attend to our own affairs, conserve our own strength, and protect the interests of our own citizens; but we recognize thoroughly our obligation to help others, reserving to the decision of our own judgment the time, the place, and the method. We realize the common bond of humanity. We know the inescapable law of service.

“Our country has definitely refused to adopt and ratify the covenant of the League of Nations. We have not felt warranted in assuming the responsibilities which its members have assumed. I am not proposing any change in this policy; neither is the Senate. The incident, so far as we are concerned, is closed. The League exists as a foreign agency. We hope it will be helpful. But the United States sees no reason to limit its own freedom and independence of action by joining it. We shall do well to recognize this basic fact in all national affairs and govern ourselves accordingly.”

The vision he explains here, a policy that protects American sovereignty while exercising the readiness to help in times of need, held consistently in each of the many foreign conflicts encountered during his five years and seven months in office. Through the violence erupting in Mexico, the issues of reparation payments in Europe, the involvement in a World Court, the “outlawry of war” movement and the restriction of Japanese immigration, Coolidge and his Secretaries of State, Charles Evans Hughes and Frank B. Kellogg, navigated safely through some very uncertain waters. As we know from more recent experience, “official” peacetime does not eradicate the explosive possibilities ever present in world affairs. Contrary to what many perceive to be an uneventful footnote in history, the peace experienced during the Coolidge administration was not merely accidental. The foreign policy articulated by President Coolidge could easily have succumbed to any one of a series of foreign conflicts during his time. Coolidge did not presume to be a brilliant diplomat. He was simply reaffirming President Washington’s admonition to avoid entangling ourselves by the promises we make to other nations, subjugating American lives and independence to foreign designs. His first loyalty was to America and its protection, in fidelity to his sacred oath. It is a sound policy in any era.