At the ninth meeting of the Business Organization of the Government, held in June 1925, President Coolidge reminded the States how they can help or hinder responsible Federal Budgeting, “Unfortunately the Federal Government has strayed far afield from its legitimate business. It has trespassed upon fields where there should be no trespass. If we could confine our Federal expenditures to the legitimate obligations and functions of the Federal Government a material reduction would be apparent. But far more important than this would be its effect upon the fabric of our constitutional form of government, which tends to be gradually weakened and undermined by this encroachment. The cure for this is not in our hands. It lies with the people. It will come when they realize the necessity of State assumption of State responsibility. It will come when they realize that the laws under which the Federal Government hands out contributions to the States is placing upon them a double burden of taxation – Federal taxation in the first instance to raise the moneys which the Government donates to the States, and State taxation in the second instance to meet the extravagances of State expenditures which are tempted by the Federal donations.”

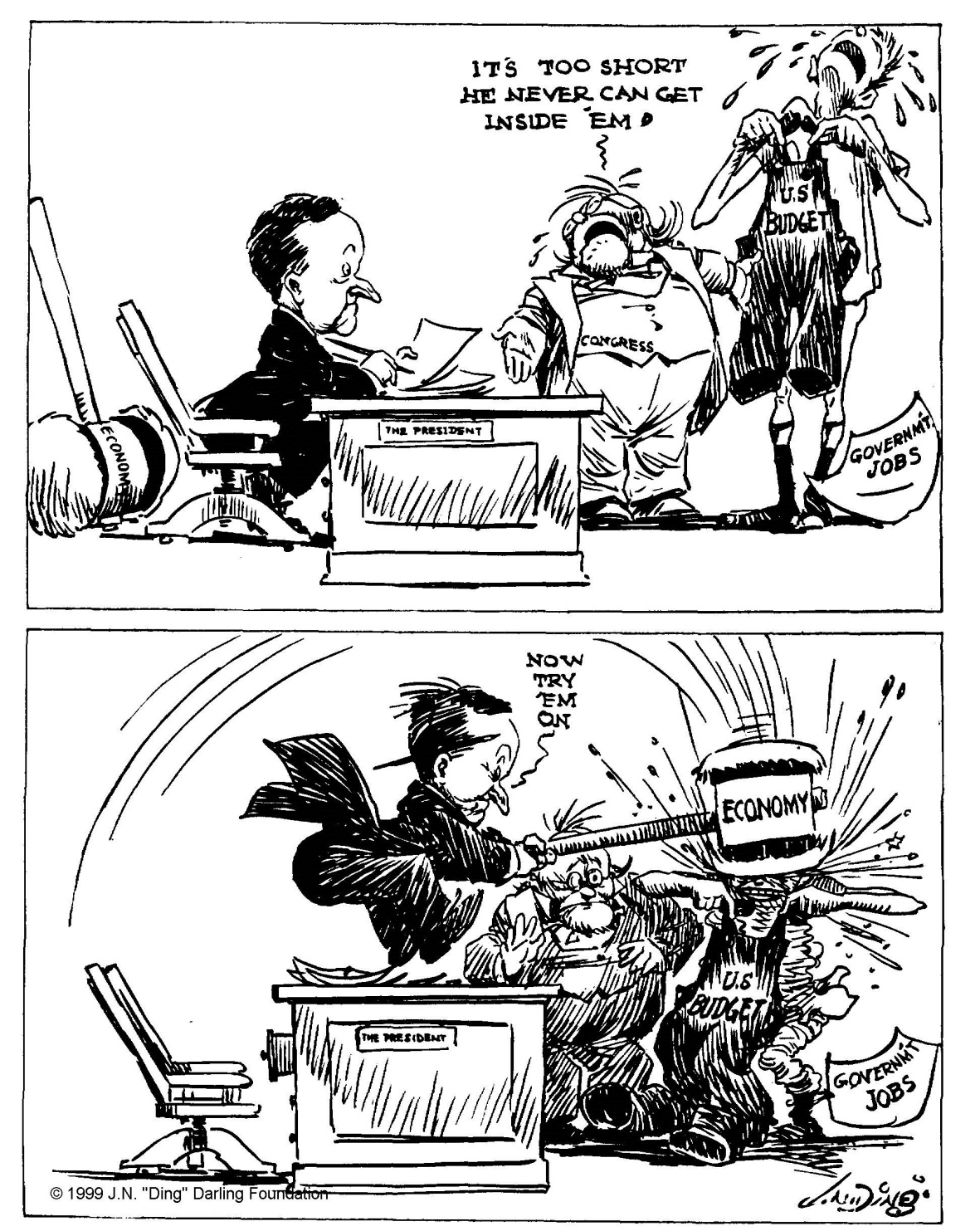

When the Business Organization of the Government met for their eighth bi-annual meeting in January 1925, the impact of the Revenue Act, passed the previous June, had taken hold and was refueling the economy with a 12% reduction in the top marginal income tax rate. Having estimated a sharp drop in receipts after the cuts took effect, the Coolidge administration would report in November that while revenue had dipped slightly, the Revenue Act had furnished unforeseen capital to compensate, producing a $250 million surplus. What was thought by critics to be a bleak future of government receipts drying up with the decrease in taxes was proving to be a baseless fear. Revenues were beginning their historic climb through the rest of the decade thanks to tax reduction. This confidence in holding to the current course, however, was anything but firm when the department heads, bureau chiefs and agency directors met with President Coolidge and General Lord that January. It was not at all clear what tax cuts would do to the budget plan. Also, the very tangible successes of the past four years under the Budget Act had been a team effort. The President could not have done it all alone. It was the result of a conscientious collaboration between the President, the Congress and the diligent men and women of the Executive Branch who took what Coolidge was “preaching” and put it into genuine practice, as he reminded his audience at the ninth meeting in June of 1925. Without everyone doing their part, Coolidge’s efforts to “preach economy” would be “in vain” and the paramount goal to remove the people’s burden would be denied, perhaps indefinitely. It remained to be seen whether everyone had the will to stay on board and help keep constructive economy moving forward. Would the pressures to spend be too much for Congress or the department heads?

“If the budget is too small for the expenses, cut down the expenses,” by “Ding” Darling, Des Moines Register, January 30, 1925.

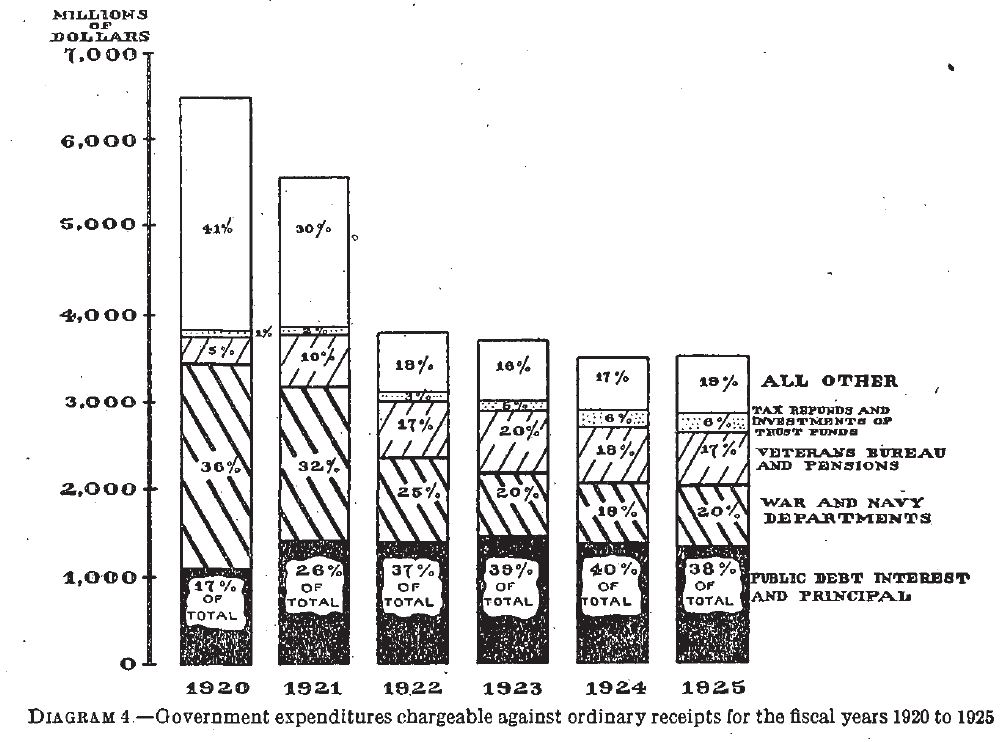

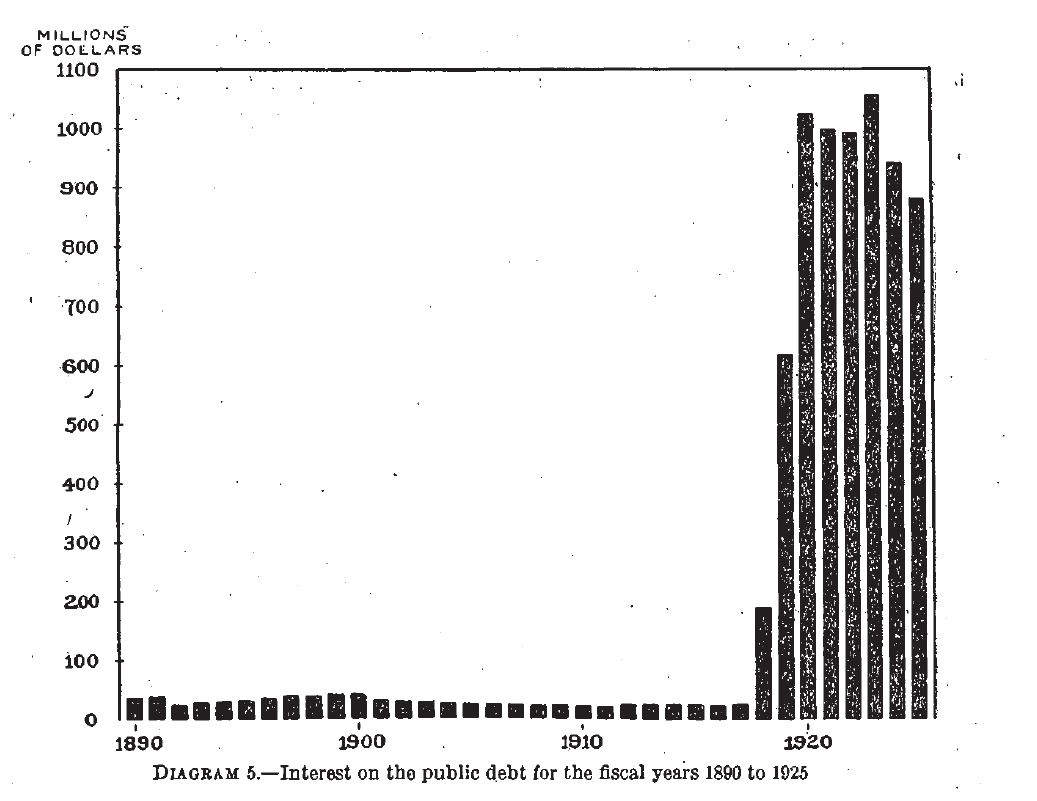

The results confirmed what had been accomplished thus far. Expenditures were down over $2 billion from where they had been four years before, while some $3.2 billion had been paid on public debt in that same time span, making possible some $134 million saved in annual interest payments. As a result, interest payments had plummeted. America’s credit standing was even stronger than before the war. Outlays were now half the size they had been in 1924. More than one third of the late war’s $33 billion had already been paid by the people themselves. They had loaned another $23 billion to their government. This debt could not be welched and increasing it would only prolong the suffering of an already over-burdened people. This was concrete progress, not budgetary sleight of hand or abstract talk without substantive action. These were not mere reductions in budget estimates either. Real reductions were now reaping real rewards. However, this would not perpetuate on its own, it demanded renewing effort to continue.

Taxpayers, the ones whom General Lord would call America’s “115 million shareholders,” were finally beginning to see the oppressive weight of war expenses gradually lift. Each year for the past four years had seen the benefit of $2 billion less in taxes. The collaborative work of so many had to persist for such immense good to continue. “Every dollar” mattered to that goal. For Coolidge, it was economy at its most practical. “I had rather talk of saving pennies and save them than theories in millions and save nothing.” Here was not only a supreme test of discipline for each person involved but it was a campaign being waged for interests that were not contradictory but inseparably joined between taxpayers and the Government who serves them. “Their interests are our only interests,” the President would declare. Reducing taxes was the central objective, not merely for a particular class or segment of the population, but as the best means of serving everyone. The people had borne up “uncomplainingly” for years what the war had incurred. By adhering to the business plan under which Government had operated four years, the economy would continue to furnish the results that rightly rewarded both the people and each department for their patient sacrifices. Consequently, this would support and sustain the prosperity that was now reaching into every part of the Nation.

“Even greater watchfulness, greater care over our expenditures, must be exercised successfully to continue this campaign. The task is becoming more difficult, but the more difficult the task the greater is the reward of success” — Coolidge, Ninth Meeting of the Business Organization of the Government, June 22, 1925

As the President made clear, however, the “heaviest single item of our expenditures” was personnel. Federal wages had undergone a 54% increase since 1913 while the civil service had added an average 12,777 employees per year for each of the last nine years, totaling just under 555,000 on the payroll. At the June meeting in 1925, the President would take up this issue again. Coolidge observed in both January and June that while the first twenty years preceding 1915 had seen a higher annual percentage of personnel expansion, the challenge to reduce, not grow, the size of Government’s payroll, deserved ongoing vigilance, if economy, even in personnel, was going to win over inefficiency and extravagance. Coolidge found this difficult to justify as reflective of any actual increase in the cost of living. The solution, however, was not to decrease wages but to “look for” a “reduction in the number of employees.” Coolidge knew this to be no simple task. He knew the quality of those who then comprised the Federal civil service. Yet, as he made plain, the “Government service” is not the repository of permanently insulated careerists, those forever cut off from the realities of private sector experience but is and will remain, under his administration, a “training ground…for commercial interests.” Individuals may start in Government but they would be expected to take what they had learned forward into the service of our vibrant commercial life flourishing around the country. The implementation of a formal reorganization of the civil service commenced in November would guide the various department heads and bureau chiefs as they carefully evaluated personnel.

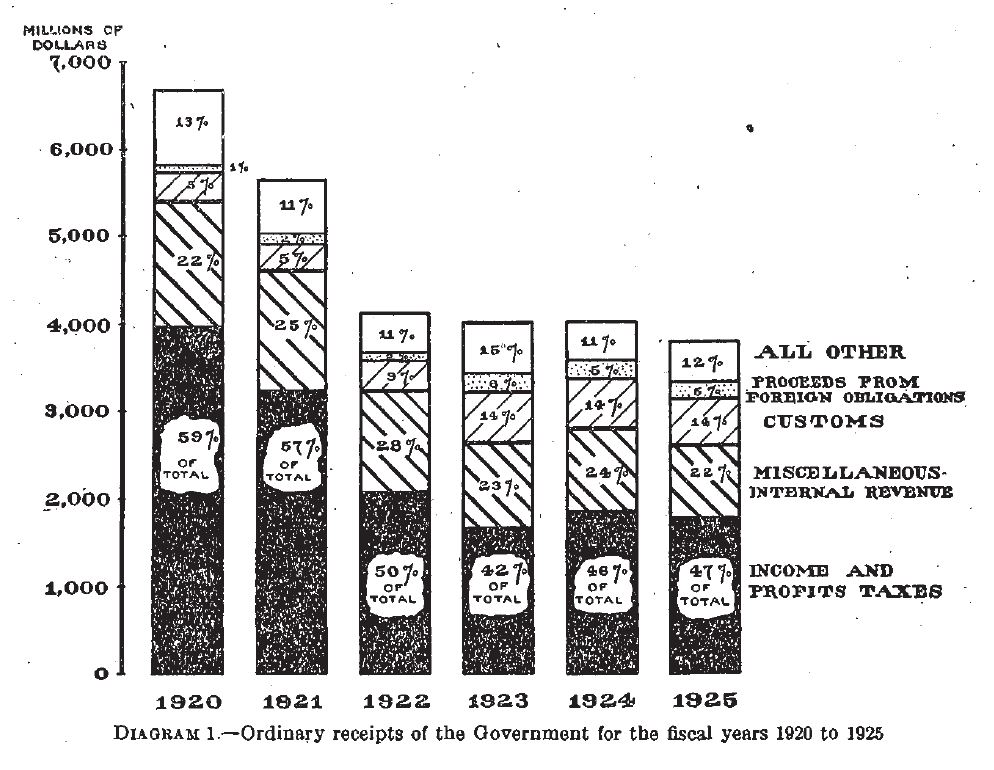

Annual Report of the Secretary of the Treasury on the State of the Finances, 1925. Courtesy of Fraiser, http://fraser.stlouisfed.org/.

Annual Report of the Secretary of the Treasury on the State of the Finances, 1925. Courtesy of Frasier, http://fraser.stlouisfed.org/.

Coolidge was not advocating “an undermanned public service. This would be false economy and disastrous in its results.” What Coolidge advocated was “the closest supervision over…personnel requirements so that any surplusage may be prevented…Wastrels, careless administrators of the Government’s substance, are out of place in the Federal service. They will not be tolerated.” He keenly knew every employee reduced was a human being, likely with a family beholden to him or her. All must serve this greater crusade of economy, even when it meant trimming avoidable costs on the payroll, as sound businesses must, to remain solvent and productive. “If this policy means sacrifice, it is sacrifice for the benefit of 115,000,000 people. Their interests are paramount. Criticism by a few who look askance at drastic paring down of spending, has little weight in the scale against the spontaneous commendation of the millions of people who have had brought to them with unmistakable clearness the result of such economy.” The “strongly urged desires of a class should have little weight with you if adverse to the interests of the whole people,” Coolidge reminded those gathered at the Business Organization meeting that summer of 1925.

Despite the claims of critics that economy was hurting business, the contrary was evident for all to see. “Each tax reduction has been followed by a revival of business. If there is one thing above all others that will stimulate business it is tax reduction. If the Government takes less, private business can have more.” Economy is the very thing that prompts “enterprise and investment.” Economy had already and would continue to serve, usefully employ and free America. A full harvest would continue to yield for those who kept on track. Of course, this entailed sacrifice but the reward of the people’s faith in their Government departments doing what was necessary far surpassed all losses. Neither did economy mandate always saying “no,” ever subtracting and never adding. As Coolidge reminded his audience, a “[g]reater ultimate economy in Federal expenditures can sometimes be attained by larger annual outlays on some of our existing projects. In fact, greater ultimate economy can in some instances be attained by undertaking new projects.” “[O]ur present objective,” the President reiterated, “is the relief of the taxpayers of to-day.”

This reveals in sharp relief the Harding and Coolidge focus not only to reduce spending but to chop down the debt of the nation, pouring massive energy into bringing those interest payments down year after year.

As the President prepared to turn the evening’s program over to General Lord at the January meeting, he turned the attention of the room to the “invisible audience” listening on the radio. They were the people “in whose interests we are gathered. They are watching our efforts in their behalf.” The joint effort of President, departments and Congress had not flinched the past four years. “We will not fail them in the four years to come.” Assuring all his listeners of one thing, Coolidge resolved to continue the “pressure for economy.” Of that, he affirmed, there “must be no retreat.” It was, after all, “a great work,” in which all were engaged. After the war had assumed so much control into the hands of government, it was nothing less than “the restoration, the return of the property, the freeing of the person.” Even that most worthy of work had its detractors, as they knew. There were “those who scoff at, who can not see and who do not know, rabid partisans who think they can advance their cause by perverting the truth to the injury of their fellow countrymen. But the great body of the people see and know. Their gratitude is yours…But not until you are done will American opportunity again belong entirely to American youth, or the restraints and servitudes be removed which will leave America entirely free.” For that incomparable freedom, all must contribute their “steadfastness” and “courage.” It was a resolve and bravery not simply for themselves or the security of their positions but for the distant future as much as the present, those generations not yet born, who would either be enslaved later by profligacy now or all the freer for having held government to economy for another year. It was with this in mind that the public officers of the Coolidge era strove so mightily. “You must not, can not, fail.” Coolidge and those who heard him that day did not.