While Mr. Walker delves into an area of study oft neglected these days, he, like Eric S. Yellin in his Racism in the Nation’s Service: Government Workers and the Color Line in Woodrow Wilson’s America, indulges in more than a fair share of unwarranted generalizations, especially when it comes to the Coolidge years.

Yellin acknowledges that Coolidge had a more “sympathetic” outlook for individual blacks than Wilson did, yet he assigns Cal into the realm of insufficient action on the race issue (p.185). For Yellin to conclude that Coolidge ultimately conceded to Wilson’s departmental segregation, he must avoid the removal of Colonel Sherrill over government property, for insisting on the old prejudicial policy, replacing him with Colonel Grant, who was known for fair and even-handed dealings on racial conflicts. The claim that the Coolidge administration targeted Perry Howard for his skin color rather than his repeated violations of ethics laws is patently absurd. Yellin must also omit the selection by Coolidge of qualified individuals as judges like James A. Cobb, political supervisors, especially in restoring equitable and competent management of the Veteran’s Hospital at Tuskegee, and as diplomats, documented here and here. The grant of full citizenship to American Indians and authorization of a full study, the Merrill Report (conducted deliberately outside government auspices), both accomplishments of Coolidge, receive little or no acknowledgement when civil liberties are considered. Sherman, in The Republican Party and Black America, rightly illustrates Coolidge’s actions against specific violators of a restored desegregation, such as the Pension Bureau of the Interior Department and elsewhere like the Census Bureau (pp.218-221). With the same token, Coolidge would not simply appoint candidates to “black seats” in the interest of fulfilling political expectations.

Walker, on the other hand, can only identify one praiseworthy act on the part of Coolidge regarding civil liberties: the appointment of Amherst classmate, Columbia’s Dean, the apolitical Harlan Fiske Stone as Attorney General in 1924 (pp.53-55). Consequently, wiretapping and political targeting stopped, the Justice Department was cleaned up, its “Dollar a Year Men” removed and entrapment practices halted. In the next breath, Walker condemns Stone and Coolidge for then failing to recognize the threat of placing then-young J. Edgar Hoover over the Bureau of Investigation that same year. Walker seems to lose his way in the thick of his material, later clarifying that it would be twelve years later, after young Hoover had undergone a significant transformation in government service, that political targeting practices resumed at the order of President Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1936 (p.95). This was long after Coolidge had died and Stone was then a Justice on the Supreme Court. To attribute blame to either Coolidge or Stone for being “fooled” by what Hoover would become and later do defies reasonable analysis. It sounds like a desperate attempt to absolve F.D.R. of something for which there can be no justification, laying the wrong at the feet of predecessors who can no longer respond to such attacks. This kind of “area-of-effect” detonation rather than “point” approach to the historical record has no place in serious study.

Judge James A. Cobb (center), appointed by Coolidge to the D. C. bench, watches a Howard University football game with friends, 1930.

Both Yellin and Walker, like all of us at times, default to the easier course: rather than do the heavy-lifting of examining all the primary sources pertinent to the Coolidge record, we impose our views of the present on the understanding of the past, interpreting events through our own eyes rather than through those who were there. When we exercise the additional discipline of standing in the shoes of those who come before us, we find that the course to navigate was not so transparent or unobstructed as hindsight leads us to believe. James Weldon Johnson and the NAACP sought federalization of responsibility for racial difficulties, whereas Coolidge, who defended a Federal anti-lynching law every one of his six years in office (long after many had given up on its passage), understood that the problem went far deeper than any law generated from Washington could remedy. It was a problem in the individual human heart. No Congress, no President, and no Court could remedy what only each one of us must conquer in our own selves, despite the growth of government being advocated by groups like the NAACP. He heard them out, he corresponded with them, met with them in the White House but he would not issue blanket proclamations for any petitioner, white, black or otherwise, that experience had taught him become independent with time from the particular facts, specific individuals wronged, and actual abuses that created them, growing into autocratic rules of conformity all their own living at the behest of whomever holds the power of interpreting them. Coolidge knew the best of intentions were not enough and no man could be in possession of every possible fact or contingency that would corrupt even the best-worded general proclamation. This is why he addressed cases as they came to him, rather than asserting broader executive authority over people not yet wronged and over actions not yet committed. If Walker praises the improvement of the Justice Department along these very lines under Stone, he is remiss in recognizing Coolidge’s equitable approach overall.

These are some of the challenges under which correction of the Coolidge record labors. Reversing the eight years of regression under Wilson and curb of ongoing abuses after 1921, would be a difficult task for anyone. Coolidge, for right or wrong, determined to lead by example, standing up for the downtrodden and honoring the neglected when it was perhaps easier than ever to ignore the injustices, take no sides and make no waves. He went to watch Negro baseball teams in a time when the Klan vilified them. While many suspected Jews, Catholics, blacks and immigrants, Coolidge remained one of their most steadfast champions. He made plain where he stood by encouraging the heroism of Americans like Mr. Thomas Lee, praising those who wore the uniform like Sargent Henry L. Johnson, publicly defending the constitutional rights of men like Dr. Charles H. Roberts, and correcting instances of Executive Branch segregation.

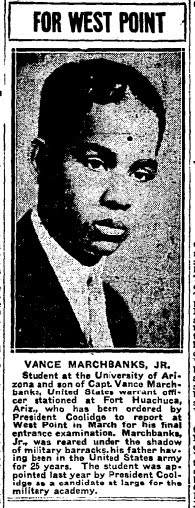

Newspaper article from 1926 featuring Van Marchbanks, Jr., who was approved for entrance exams into West Point by President Coolidge. Hardly accorded special privileges, the young man was barred from taking the exams once he arrived at his appointed station in Texas. Young Marchbanks would persevere, however, finishing the University of Tuscon, completing medical school at Howard University, becoming one of the first Tuskegee Army Air Field Medical Officers, and eventually, the head surgeon in the space program overseeing the astronauts of John Glenn’s crew. Coolidge’s appointment was anything but racially-driven, he must have seen something in what he could learn of the young man to so act on his behalf. Courtesy of http://lingeringthoughtslovingtimes.blogspot.com/2012/04/marching-marchbanks-arizona-connection.html.

He took these actions, not because he had to, but because he understood that the President holds a great responsibility of moral example. Just as he would not condone the victimization of targeted individuals, so he would not expand the grasp of Presidential power to solve problems no single man could, however great the authority. The loss of constitutional liberties for everyone lay in that latter direction, as many had experienced just a few, short years before. What the country needed now was not a new explosion of Washington’s regulatory reach into social failings but a reclamation of personal responsibility over government and human affairs by each individual. The nation needed a confidence that government began in the heart and mind, not in Federal Offices. Even so, Americans needed to see in their President a demonstration of that ideal — that simple self-government supplies what is missing in our dealings with each other. Coolidge understood what many who have come after seem all too ready to countenance: elaborately-planned, unendingly-financed, failed programs that rest on a mountain of good intentions and comforting rhetoric mean more for their “peace of mind” than the value of actual liberty. These programs ultimately cause a free people to doubt themselves and trust implicitly on the superior competence of a central authority.

The record Coolidge wrought deserves a new, honest appraisal and not a moment too soon. As we head toward very uncertain waters as a nation, America needs good anchors, ideals that strengthen and hold true whatever the current circumstances. America has an enduring and steadfast anchor in the principles of Calvin Coolidge. Will we make use of them?

Reblogged this on The Importance of the Obvious.