The Coolidges, sitting with Louis B. Mayer, Will Hays, Mary Pickford and others at the MGM Studios, watching a performance by Ramon Navarro, 1930.

So, what did Calvin Coolidge do for art and artists, from the canvas to the gallery and the camera to the theater? We have already begun a look at the portrait painters who received such generous support from the not-so-silent Cal, but what of the performing arts?

As Mayor of Northampton, Coolidge performed in a community history play, summer 1911, as Chief Chickwallop. Of course, as a young boy he also participated in amateur productions, including one as a villain.

While both Mayor and Governor, he frequently took advantage of the theater tickets offered to him. While he attended both dramatic and comedic performances, he preferred comedies, vaudeville and burlesque shows. As President, Coolidge took particular delight in the slapstick and parody of Gridiron Dinners, the annual performances put on by the Washington Press Corps. Both Coolidges enjoyed Gilbert & Sullivan comedic operas. In fact, Mrs. Coolidge would declare in her letters to college friends: “Anybody who does not appreciate Gilbert & Sullivan ought to be taken out and shot at sun-up.” Or perhaps, dare we suggest, experience a short, sharp shock on a big, black block?

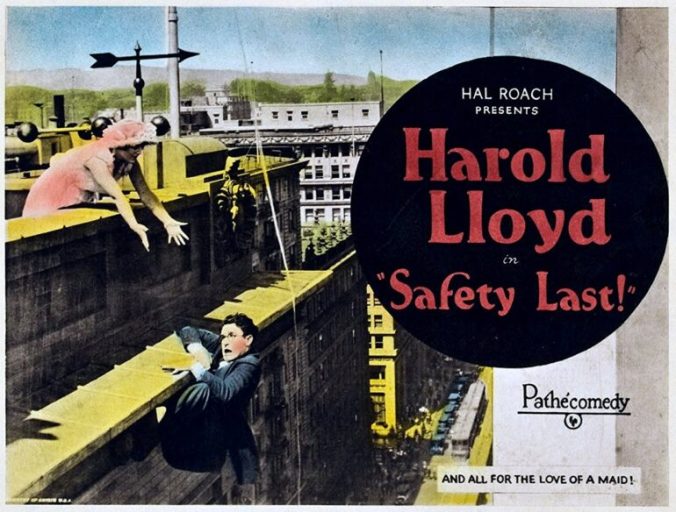

It appears that Coolidge especially enjoyed Harold Lloyd’s comedies but he also found enjoyment in the Marx brothers and Buster Keaton. Among his closest friends were stage actor Otis Skinner and his wife, Maud. Cal usually kept to himself any reviews of shows he had seen, however, and friends would only find out what he thought of a show when he confessed to going back two or three times to especially good performances. Coolidge’s observation that the most effective method of driving out evil is by filling with good, can as easily translate to culture as it does to politics.

As President of the Massachusetts Senate, he helped address local concerns about the D. W. Griffith film “Birth of a Nation,” shown in local theaters beginning in April 1915. Its lionization of the Klan and clearly critical slant of African-Americans earned it intense opposition among many that spring around the state and even nationally. Coolidge supported a Senate bill creating a commission of three (including the state Governor) which gave majority approval to the showing of films in the state. He cast the deciding vote that defeated any attempt to kill the measure by reconsideration and quietly worked to ensure that while the film continued to show in theaters, it would be accompanied by footage of the work progressing at Tuskegee and Hampton Institutes for the betterment of African-Americans.

As Governor of Massachusetts in 1920, he vetoed a General Court bill to subject every sale, lease, showing, and even transport of films to censorship. He opposed it as a poorly written piece of legislation that not only endangered due process but most especially intruded upon the federal power to regulate interstate commerce as provided in the U.S. Constitution.

The Coolidges on the set at MGM, 1930. Photo credit: Shutterstock

Coolidge was an eager patron of the arts, including film, and saw its potential for good early on…not only were musicales a regular part of the White House but so were the evening showings of films in the mansion, on the Mayflower, and at the summer White Houses in Swampscott, White Pine Camp, Rapid City, and on the Brule River. He dedicated the new National Academy of [Arts and] Sciences in 1924, attended the International Exhibition of Paintings at Carnegie Institute in Pittsburgh, was a studious observer of what art said about the health of culture (as he shared in conversation with British visitor Beverly Nichols, “The Star Spangled Manner,” 111-123), seeing the health or turmoil in national moods reflected in the art of each country. The arts were often prophetic visions of where a culture was going or a gauge of where it was, both the healthy and diseased.

Coolidge was grateful for the new Chamber of Music (though not a music enthusiast like Mrs. Coolidge) which was added to the Library of Congress in 1925. Even his own uncle, John Wilder, would ply his abilities as a fiddle player on vaudeville for a time, delighting audience with tunes that Cal often heard growing up in Plymouth. Coolidge brought attention to the educational possibilities of art by dedicating numerous artistic monuments and memorials to historical figures.

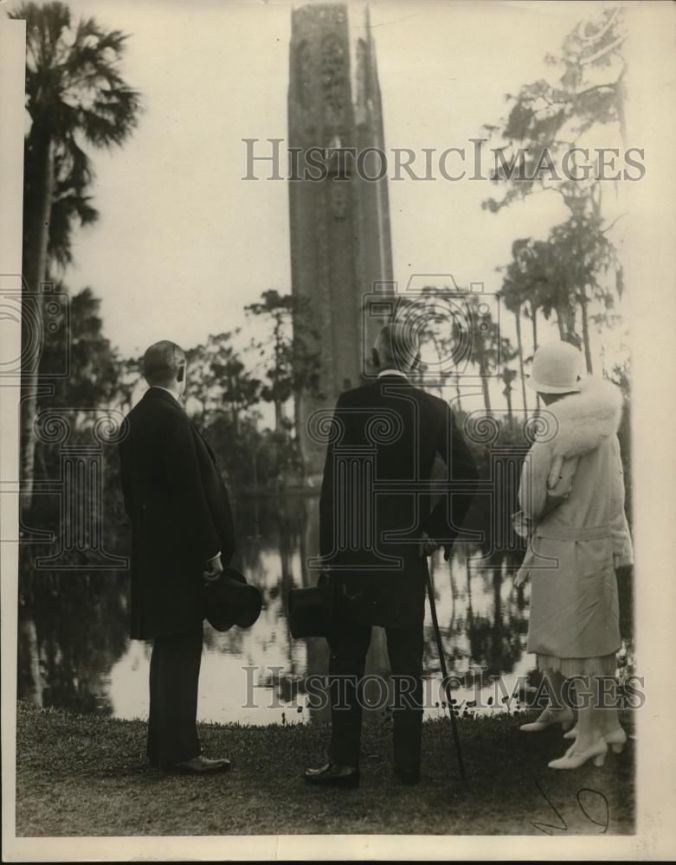

The Coolidges and the Boks look across the sculpted lake to Mr. Bok’s Singing Tower, February 1929. Photo credit: Historic Images.

Coolidge cherished great interest in landscapes and portraiture including a portrait done in the 1920s of Crispus Attacks, the African-American killed at the Boston Massacre. He had great interest in using artists outside the U.S. Mint to obtain wider talent in the design of American medals. He dedicated the Bok Tower site in Lake Wales, a monument to beauty, giving a speech in great praise on the topic. He defended the vitality and importance of cultural and artistic pursuits (best encapsulated in his speech as Vice President to Wheaton College in 1923, “The Things That Are Unseen”). Not only did Al Jolson, John Drew, and forty other actors pay a visit to the White House in October 1924 but the Barrymores (John and Ethel, especially) along with Jane Cowl, Charlotte Greenwood, Mary Pickford, Douglas Fairbanks, Tom Mix and many more found the Coolidges to be gracious hosts at the White House. Tom Mix (later the first Mayor of Beverly Hills) would be invited to perform tricks with his horse for the veterans at White House garden parties. Will Rogers would stay as a guest at the mansion. Musical performances were regular parts of life and choral groups found frequent encouragement to perform for various events, including Christmas – the singing of carols being a favorite feature of the season in the Coolidge administration.

The Coolidges with John Drew, Al Jolson and others, South Portico of the White House, October 1924. Photo credit: Library of Congress.

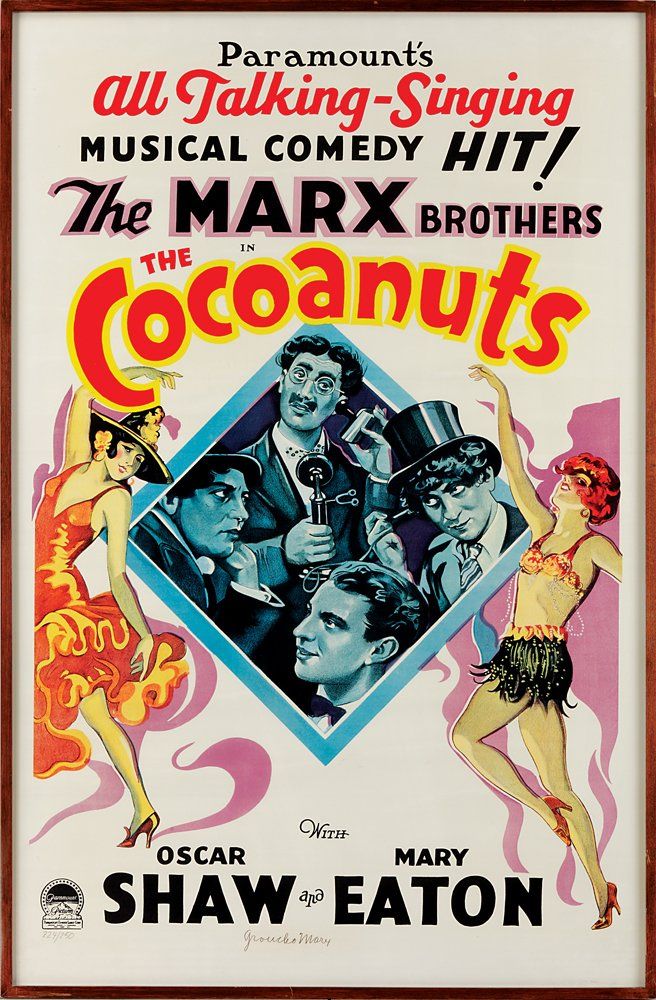

Coolidge would frequently inquire of his Secret Service man, Colonel Starling, what was showing at Keith’s or Poli’s Theater on a given night so arrangements could be made to go. When the “dean of American theater,” David Belasco, met Coolidge at the White House, Belasco said: “Mr. President, this is the greatest honor” to which Cal replied: “No, Mr. Belasco, there have been many Presidents, but there is only one David Belasco” (Ishbel Ross, Grace Coolidge and Her Era, 164). When the Marx Brothers brought their production, “The Cocoanuts” to Washington, the Coolidges attended and the audience was more struck by the President’s reactions than the lines of the performance.

Poster for the 1929 film version of the theatrical production

Perhaps the biggest answer to what Coolidge did during his Presidency on behalf of the arts was to firmly oppose federal film censorship culminating in 1926 through the Upshaw bill, introduced by Congressman William D. Upshaw (D-GA) that would have created a Federal Motion Picture Commission and strict regulations of that medium across the country, reposing that authority in the Department of the Interior. Coolidge condemned such a move in a press conference on April 20, 1926, and the bill shortly thereafter went down in flames, dying in the House Education Committee. Congressman Upshaw proceeded to attack President Coolidge for his stand but Cal stuck to it. Coolidge believed censorship questions rested not with the federal government but with the people of the states and their elected officials at the local level. A healthy dose of self-policing by movie makers would not go amiss either but Washington should not be in the business of building what thoughts and dreams people are allowed to have.

It is a clear support for the arts that Coolidge not only patronized theaters, watched news and commercial film, held musicales and provided entertainment for the veterans at garden parties, hosted vaudeville troupes and musicians (with all the notoriety a visit to the White House entails) but he also did not seek to pick favorites, showing equal opportunity and shunning attempts to use the limelight either for himself or to advance an individual’s career. When Broadway actress Louise Dresser sent a large goose to the Coolidges in advance of her role in “The Goose Woman” hitting theaters in 1925, they quickly saw it for what it was: a publicity stunt they would not endorse. The goose went quietly away.

After the White House, the Coolidges made a cross-country trip attempting to be anonymous private citizens again that included Hollywoodland and the MGM Studios. Though they could travel few places without crowds, they genuinely tried to enjoy the journey. The excursion had its lighter moments, for sure. When a trained bear escaped during their visit to the studios, it amused Cal thoroughly to see the frantic desperation of its trainer and the crew struggling to handle the situation. He was no Hollywood groupie but he could respect the technical skills, creative talents, and spiritual inspiration film made possible.

Coolidge with Mr. Mayer while Mary Pickford, Grace Coolidge and Will Hays converse in the background.

When the topic of dancing at inaugural balls came up in a press conference on December 23, 1924, Coolidge gave his thoughts: “I approve of people that like to dance dancing as much as they wish.” While he did not much care for dancing personally, he had learned how as a young man. Moreover, he encouraged his boys to learn dancing as well and to play an instrument or two (which Grace enthusiastically oversaw).

It is important to remember that Cal could see a worthwhile place in interests he did not share. That is sometimes missing in policymakers, who occasionally spend more time than is helpful imposing their own cultural preferences and tastes into law on the rest of us. While it is obvious that Cal was not the “life” of most parties, he didn’t see a need to be so. The Universe was not about him. Others were better suited to be the funniest or most companionable at parties, that was not him and he would not be false to himself. He would humbly defer to their aptitudes in that sphere. He did not need to be the at the center of things to feel secure in his skin or fulfilled at life. He saw this to be true in all professional pursuits, not only art. He understood the range to dream and imagine was as broad as the number of individuals. Laws that denied the human quality of dreaming big dreams could do great harm. Government could not, and should not try, to fill that spiritual and cultural impulse. That was where faith and eternal truths preside not planners planning a world in their own image. Culture could not be treated by lawmakers with cookie-cutter efficiency, without dehumanizing humanity.

When the Coolidge Theater finally opened in their home town of Northampton, Grace occasionally went to see the latest show but Cal, it seems, never did grace the threshold. That was fine by him. He had not lost his appreciation for the creative or beautiful but he did not believe his own preferences should restrain others from a good time, a little laughter, and harmless entertainment.

The Coolidges on the lot at MGM, 1930. Photo credit: Coolidge Family Papers, Vermont Historical Society.

I think you may be confusing Marie Dressler with Louise Dresser. It was the latter who appeared in the Goose Woman. She spelled her name without the “l.”

Thank you for the observation. Marie (1868-1934) and Louise (1878-1965), being contemporaries in theater and film, are often confused with each other, even Margaret Truman blends the two in her 1969 book, White House Pets. It makes it all the more perplexing that Louise (not Marie), playing the title role in “The Goose Woman,” wears two names in the film, opera star Maria di Nardi and Mary Holmes.