“Here about us, in this place of beauty and reverence, lies the mortal dust of a noble host, to whom we have come to pay our tribute, as thousands of other like gatherings will do throughout our land. In their youth and strength, their love and loyalty, those who rest here gave to their country all that mortality can give. For what they sacrificed we must give back the pledge of faith to all that they held dear, constantly renewed, constantly justified. Doing less would betray them and dishonor us.” — President Calvin Coolidge, Memorial Amphitheater, Arlington, May 30, 1925

Established as a day of decorations and tributes to America’s fallen, both North and South, Memorial Day continues to carry enduring importance not as an occasion to glory in the wars of the past, satisfy the vanity of the living or act out some tedious annual ritual of feigned gratitude. What we give on that day is not so that it may be seen. Better that we give nothing at all than give with an eye to be noticed and praised. If it be not sincere, you have nothing to display but your own mendacity. If the principles for which the fallen gave live anywhere, they must live in the hearts of the living. Decoration Day was created to reflect upon self-denying sacrifice and the cost of that sacrifice in service to national ideals (that is, the principles brought together from across the centuries to form America’s foundation stones), whether that unknown soldier falls on the farmland of Gettysburg, in the forests of Argonne, on the beaches of Iwo Jima or Normandy, all gave everything there was to give for something beyond the material, something above the physical, something eternal. We cannot begin to repay what the fallen gave to millions they would never meet but neither should we attempt to devalue the debt.

It was in that spirit of sincere thankfulness that the people of Great Britain reverently interred at Westminster Abbey the first unknown soldier of World War I in 1920.

It was in that spirit that Judge Ivory G. Kimball’s vision for a place that would become the Arlington Memorial Amphitheater (constructed of marble quarried in Danby, Vermont, and imported from Botticino, Italy), and replacing the smaller, wooden amphitheater of Arlington House, had already been dedicated two weeks before Decoration Day that same year.

It was in that spirit that Americans began their own quest to bring home a representative of our soldiers, sailors, and Marines who remained beyond individual identification in the distant grounds of Europe’s cemeteries.

Selected on the morning of October 24, 1921, before both American and French forces at the City Hall in the city of Chalons, Sergeant Edward F. Younger (whose distinguished service in the American Expeditionary Force bestowed the honor) selected one of four caskets in which had been placed the remains of men who had been placed at Aisne-Marne, Meuse-Argonne, Somme and St. Mihiel. With white roses in hand, Sergeant Younger quietly circled the caskets three times and placed the roses on the third from the left, facing it squarely and saluting. As preparations for the journey across the Atlantic aboard the USS Olympia culminated, the casket lay in state and under guard for a few brief hours. With flags at half-mast, the Olympia carried the revered cargo into Washington’s Navy Yard on November 9, 1921. Draped with the flag, the casket was escorted to the Capitol rotunda supported by the same catafalque which had held Presidents Lincoln, Garfield, and McKinley.

Thousands paid their respects the next day before solemn procession on November 11, would bring the unknown soldier to final rest at Arlington National Cemetery, in the plaza of the Memorial Amphitheater, due east the Amphitheater’s Memorial Display Room. The President, Vice President Coolidge, the Cabinet, former President Wilson, the Supreme Court, a number of Congressional and state leaders along with decorated military commanders and their units escorted the casket from the Capitol to Arlington.

A simple ceremony led by President Harding bestowed the service and both the Medal of Honor and Distinguished Service Cross upon the unknown soldier. Representatives from Belgium, Great Britain, France, Italy, Romania, Czechoslovakia, and Poland presented their nation’s honors: the Belgian Croix de Guerre, the Victoria Cross, the Medaille Militaire and French Croix de Guerre, the Gold Medal for Bravery, the Virtutes Militaria, the War Cross and the Virtuti Militari. Three artillery salvos, Taps, and a National Salute accompanied the internment of the soldier in a simple marble crypt as the ceremony concluded.

Memorial Day gatherings in the Amphitheater would become a cherished tradition in the 1920s and the sober presentation of a wreath on the modest tomb of the unknown soldier would mark Armistice Day each November 11. But, with the increased awareness of higher duty given came the recognition that greater honor was required the tomb. Army guards took over civilian sentries in 1926.

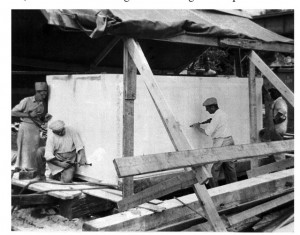

It was in that spirit that Congress appropriated the same year a new design for the tomb, something more august and befitting the dignity of the man whose entire identity remained lost, known only to God. Over 70 designs were submitted but it would be the concepts of Lorimer Rich and sculptor Thomas H. Jones whose work would emerge out of the marble of Colorado and the skilled stone finishers of Vermont — the memorial we now see. The site would continue to live and expand with the growth of Memorial Day’s meaning to include similarly chosen unknown soldiers of World War II, Korea, and finally a place which remains vacant for those missing servicemen past, present and future. If Memorial Day is to mean anything, it must live in the hearts of the living.