San Francisco and Kansas City, each in its own way, have played vital roles in the history of America. The rush in 1849 to California following the discovery of gold accentuated the need for durable work pants for the miners, a need met by German immigrant Levi Strauss who arrived in San Francisco in 1850 to begin his line of what would become known as denim jeans, originally made of tent canvas. The prairies upon which Kansas City would be founded received the visit of Lewis and Clark’s Corps of Discovery on their way to reach the Pacific in 1804. Encountering topography, people, and animals few whites had ever seen, they saw the council gatherings of tribes previously unknown, traversed the Missouri as it turned to the interior, witnessed an open and vast country of bison as far as the eye could see, the grizzly which seemed almost impossible to bring down, and still other fantastic creatures on the way. They caught a glimpse of tribal politics and the same rivalries between individuals and groups as existed among the nations of Europe. Yet, there were friends to be met too. The American West, through which so much has passed the gates of Kansas City and San Francisco, continues to inspire and intrigue. They have their heroes and villains like every other place and time in human history but they also represent something more: they are the products of vision, and would never have been had not individuals of past generations dared to create, determined to overcome naysayers, dreamed big, and done well in service to others.

Photo credit: Pinterest

The Liberty Memorial at Kansas City, dedicated by President Coolidge in 1926, who was also there when ground was first broken in 1921, stands as the nation’s foremost monument to those of all backgrounds who took up the high call of duty in World War I. They continue to be among the finest examples of what being America means. It mattered not what color they were, from where they came, or whether they thought alike in every particular, what they had in common outweighed all artificial differences. Whatever has been done to this inheritance of selflessness since does not negate that great ideals and reserves of moral power built these cities. They will continue to live for the good of people only if the same moral power sustains them in the future. Without the basis of civic pride grounded on self-government and unselfish service, our towns and cities shrivel and die. The abandoned structures only display what first happened within the spirits of those who live there. History is replete with such places that once thrived. They are dead now because citizenship first died in the hearts of its inhabitants.

So, as San Francisco and Kansas City face off today, let us walk through some of Calvin Coolidge’s words given upon his visits to each. Below are excerpts from three speeches, the first given as Vice President upon his visit to Kansas City for the groundbreaking of the Liberty Memorial on October 31, 1921. The second is Vice President Coolidge’s address to the American Bar Association, delivered for its 45th annual meeting held in San Francisco on August 10, 1922. The third is President Coolidge’s address dedicating the completed Liberty Memorial in Kansas City on Armistice Day, November 11, 1926.

Photo credit: Worthpoint

1) Groundbreaking Ceremonies, Liberty Memorial, Kansas City, October 31, 1921 (excerpts)

“It is notorious that the people of the colonies were divided. Many of their number, of most respectable attainments and most unquestioned character, doubted the wisdom of the patriot cause. When the Revolution became victorious they left by scores of thousands, or remained silent but unconvinced. In the War of 1812, with its strange commingling of the most ignominious defeats with the most brilliant victories, both by land and sea, there was grave lack of popular approval, which in some sections bordered on open resistance. The war with Mexico was widely criticised. Abraham Lincoln, while withholding no note of support for the army in the field, violently denounced the motives which brought on the conflict. The war between the States needs but to be named to show the complete division of two sections of our people, which even the war with Spain did not completely reunite. The opportunity to make this nation one, the sacrifice which made this nation one, was of your day alone. All the streams of that great spirit are gathered up in you. You represent a new national consciousness. You represent the consummation of those great forces, coming into action in the early days of this century, which not only made America more American, but made humanity more humane. The hope of this nation, which more than ever before corresponds with the hope of the world, lies in your power to minister to that spirit, to preserve that consciousness, and to increase those forces…

The prosperity and welfare–yes, more than that, the righteousness–of our country lies in the service which one section can render to another. The East found success in building railroads, opening mines, and developing the resources of the West; the West found success in feeding the people and supplying the raw products for the factories of the East; the North finds success in the sale of its manufactures in the South; the South finds success in supplying the North with the production of her plantations. This is not competition but co-operation. Fundamentally this process is right. It is the law of service. Practically it should continue because it is the only means to success and prosperity. There is no path to permanent prosperity and success which narrowly excludes any section.

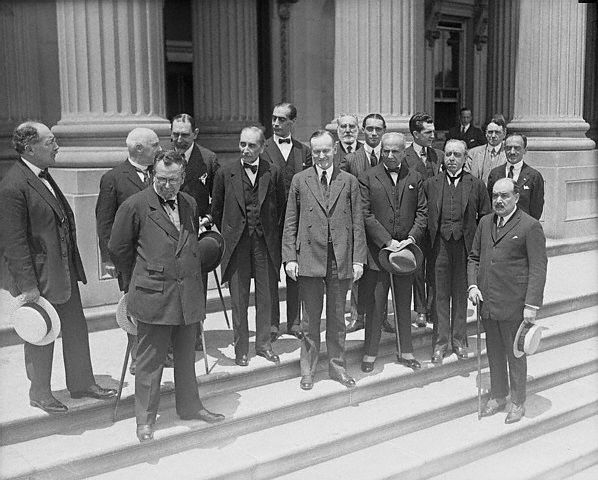

Vice President Coolidge, October 31, 1921, groundbreaking ceremony for Liberty Memorial. Photo credit: National WWI Museum and Memorial.

It is always easier to think of the part than of the whole. It is easier for men to remember that they work at the plough, the forge, the drill, the spindle, the bench, the desk, or that they follow transportation, the law, medicine, banking, or the ministry than it is to remember that into the life of every man there goes a part of all these activities, and many more, and that whatever his occupation, each is a part of the whole nation, and this the permanent prosperity of each will stand or fall with the permanent prosperity of the whole. No man is wise enough, no combination strong enough, to transgress this law and long escape its penalties. All artificial privilege always has and always will destroy itself. The law of service is a law of action. No artifice can long circumvent it; no fraud can long cheat it. The United States Constitution is right. Titles to nobility cannot be granted or seized. They can only be achieved. They come through service, as yours came, or they do not come at all. If men in civil life, in these days of peace, would put their thought and effort into the success of the people of the whole country, as in military life you put your thought and effort, in time of war, into the success of the whole army, the victories of peace would follow as surely as did the victories of war. Government and industry, locality and society, all need the national outlook you so proudly achieved. It is time in every activity in our land, for men in every relationship, to stop trying to get the better of each other and begin trying to serve each other.

Under these circumstances, considering the great sacrifice you represent, and the great stake you have in the country, it is small wonder that you not only exemplify patriotism in your own actions, but insist, as you have a right to insist, on patriotic action in others. You have great patience with ignorance and weakness, but no patience at all with any informed and powerful attempt to make a mockery of our institutions, defy the execution of our laws, and violate the rights of our citizens. But in resisting all attacks upon our liberty, you will always remember that the sole guarantee of liberty is obedience to law under the forms of ordered government. The observance of the law is the function of every private citizen, but the execution of the law is the function only of duly constituted public authorities…

Construction of the Liberty Memorial well underway after commencing on July 5, 1923. Photo credit: National WWI Museum and Memorial.

Our own national existence presupposes the national existence of others. Were there no other countries there would be no choice between countries, and therefore no loyalty to one to the exclusion of others, no patriotism. That virtue we claim for ourselves we must recognize in others. If it be well for America to have a strong national spirit, it must be well for others to cherish the same sentiment. The war did not break this spirit; in any country it strengthened it, strengthened it for the glory of all. America first is not selfishness; it is the righteous demand for strength to serve. And America has been dedicated to an unselfish service. I weigh my words when I say that both in Europe and in the Orient that service for humanity has not been exceeded by any other nation. It will not be, then, in diminishing but in enlarging the national spirit that true progress for the race will be found. There can be society without a home, no civilization without citizenship.

But, as a true national spirit calls for a harmonious adjustment of the relationship between all the sections and all the people in the nation, so it calls for a harmonious relationship between the different nations. This is the spiritual lesson of the war.

The work of Washington was no finished at Yorktown, the work of Lincoln was not completed at Appomattox; they live in our institutions, one in the Constitution which his efforts caused to be adopted, the other in the amendments which his sacrifice caused to be ratified. Your work was not all done on the sea or on the fields of France…

I do not understand that this means that any nation is to divest itself of the power to resist domestic violence or suffer any diminution of independence, but out of mutual understandings the great burden, and it may be the menace, of competitive armaments may be removed. That is a new expression of a great hope, all the greater because it seeks the practical. It proposes something that America can do at home. It surrenders no right, it imposes no burden, it promises relief at home and a better understanding abroad. It if be accomplished its blessings will be reflected at every fireside in the land. The economic pressure of government will be lifted, the hope of a righteous and abiding peace will be exalted…”

Vice President Coolidge, June 1922

2) Address to the American Bar Association, San Francisco, August 10, 1922 (full text)

“The growing multiplicity of laws has often been observed. The National and State Legislatures pass acts, and their courts deliver opinions, which each year run into scores of thousands. A part of this is due to the increasing complexity of an advancing civilization. As new forces come into existence new relationships are created, new rights and obligations arise, which require establishment and definition by legislation and decision. These are all the natural and inevitable consequences of the growth of great cities, the development of steam and electricity, the use of the corporation as the leading factor in the transaction of business, and the attendant regulation and control of the powers created by these new and mighty agencies.

This has imposed a legal burden against which men of affairs have been wont to complain. But it is a burden which does not differ in its nature from the public requirement for security, sanitation, education, the maintenance of highways, or the other activities of government necessary to support present standards. It is all a part of the inescapable burden of existence. It follows the stream of events. It does not attempt to precede it. As human experience is broadened, it broadens with it. It represents a growth altogether natural. To resist it is to resist progress.

But there is another part of the great accumulating body of our laws that has been rapidly increasing of late, which is the result of other motives. Broadly speaking,

it is the attempt to raise the moral standard of society by legislation.

The spirit of reform is altogether encouraging. The organized effort and insistent desire for an equitable distribution of the rewards of industry, for a wider justice, for a more consistent righteousness in human affairs, is one of the most stimulating and hopeful signs of the present era. There ought to be a militant public demand for progress in this direction. The society which is satisfied is lost. But in the accomplishment of these ends there needs to be a better understanding of the province of legislative and judicial action. There is danger of disappointment and disaster unless there be a wider comprehension of the limitations of the law.

The attempt to regulate, control, and prescribe all manner of conduct and social relations is very old. It was always the practice of primitive peoples. Such governments assumed jurisdiction over the action, property, life, and even religious convictions of their citizens down to the minutest detail. A large part of the history of free institutions is the history of the people struggling to emancipate themselves from all this bondage.

I do not mean by this that there has been, or can be, any progress in an attempt of the people to exist without a strong and vigorous government. That is the only foundation and the only support of all civilization. But progress has been made by the people relieving themselves of the unwarranted and unnecessary impositions of government. There exists, and must always exist, the righteous authority of the state. That is the sole source of the liberty of the individual, but it does not mean an inquisitive and officious intermeddling by attempted government action in all the affairs of the people. There is no justification for public interference with purely private concerns.

Those who founded and established the American Government had a very clear understanding of this principle. They had suffered many painful experiences from too much public supervision of their private affairs. The people of that period were very jealous of all authority. It was only the statesmanship and resourcefulness of Hamilton, aided by the great influence of the wisdom and character of Washington and the sound reasoning of the very limited circle of their associates, that succeeded in proposing and adopting the American Constitution. It established a vital government of broad powers, but within distinct and prescribed limitations. Under the policy of implied powers adopted by the Federal party its authority tended to enlarge. But under the administration of Jefferson, who, by word, though not so much by deed, questioned and resented almost all the powers of government, its authority tended to diminish, and but for the great judicial decisions of John Marshall might have become very uncertain. But while there is ground for criticism in the belittling attitude of Jefferson toward established government, there is even larger ground for approval of his policy of preserving to the people the largest possible jurisdiction and authority. After all, ours is an experiment in self-government by the people themselves, and self-government cannot be reposed wholly in some distant capital; it has to be exercised in part by the people in their own homes.

So intent were the founding fathers on establishing a Constitution which was confined to the fundamental principles of government that they did not turn aside even to deal with the great moral questions of slavery. That they comprehended it and regarded it as an evil was clearly demonstrated by Lincoln in his Cooper Union speech, when he showed that substantially all of them had at some time by public action made clear their opposition to the continuation of this great wrong. The early amendments were all in diminution of the power of the government and declaratory of an enlarged sovereignty of the people.

Vice President Coolidge with Lady Astor, 1922. Photo credit: Corbis.

It was thus that our institutions stood for the better part of a century. There were the centralizing tendencies and the amendments arising out of the War of ’61; but, while they increased to some degree the power of the National Government, they were in chief great charters of liberty, confirming rights already enjoyed by the majority and undertaking to extend and guarantee like rights to those formerly deprived of equal protection of the laws. During most of this long period the trend of public opinion and of legislation ran in the same direction. This was exemplified in the executive and legislative refusal to renew the United States Bank charter before the war and in the judicial decision in the slaughter-house cases after the war. This decision has been both criticised and condemned in equally high places, but the result of it was perfectly clear. It was on the side of leaving to the people of the several States, and to their legislatures and courts, jurisdiction over the privileges and immunities of themselves and their own citizens.

During the past thirty years the trend has been in the opposite direction. Urged on by the force of public opinion, national legislation has been very broadly extended for the purpose of promoting the general welfare. New powers have been delegated to the Congress by constitutional amendments, and former grants have been so interpreted as to extend legislation into new fields. This has run its course from the Interstate Commerce Act of the late eighties, through the various regulatory acts under the commerce and tax clauses, down to the maternity aid law which recently went into effect. Much of this has been accompanied by the establishment of various commissions and boards, often clothed with much delegated power, and by providing those already in existence with new and additional authority. The National Government has extended the scope of its legislation to include many kinds of regulation, the determination of traffic rates, hours of labor, wages, sumptuary laws, and into the domain of oversight of the public morals.

This has not been accomplished without what is virtually a change in the form, and actually a change in the process, of our government. The power of legislation has been to a large extent recast, for the old order looked on these increased activities with much concern. This has proceeded on the theory that it would be for the public benefit to have government to a greater degree the direct action of the people. The outcome of this doctrine has been the adoption of the direct primary, the direct election of the United States senators, the curtailment of the power of the speaker of the House, and a constant agitation for breaking down the authority of decisions of the courts. This is not the government which was put into form by Washington and Hamilton, and popularized by Jefferson. Some of the stabilizing safeguards which they had provided have been weakened. The representative element has been diminished and the democratic element has been increased; but it is still constitutional government; it still requires time, due deliberation, and the consent of the States to change or modify the fundamental law of the nation.

Advancing along this same line of centralization, of more and more legislation, of more and more power on the part of the National Government, there have been proposals from time to time which would make this field almost unlimited. The authority to make laws is conferred by the very first article and section of the Constitution, but it is not general; it is limited. It is not ‘All legislative powers,’ but it is ‘All legislative powers herein granted shall be vested in a Congress of the United States.’ The purpose of that limitation was in part to prevent encroachment on the authority of the States, but more especially to safeguard and protect the liberties of the people. The men of that day proposed to be the custodians of their own freedom. In the tyrannical acts of the British Parliament they had seen enough of a legislative body claiming to be clothed with unlimited powers.

Vice President Coolidge with boy-movie star “Freckles” Barry during his visit to Washington, April 1922. Photo credit: Corbis.

For the purpose of protecting the people in all their rights, so dearly bought and so solemnly declared, the third article established one Supreme Court and vested it with judicial power over all cases arising under the Constitution. It is that court which has stood as the guardian and protector of our form of government, the guarantee of the perpetuity of the Constitution, and above all the great champion of the freedom and the liberty of the people. No other known tribunal has ever been devised in which the people could put their faith and confidence, to which they could entrust their choicest treasure, with a like assurance that there it would be secure and safe. There is no power, no influence, great enough to sway its judgments. There is no petitioner humble enough to be denied the full protection of its great authority. This court is human, and therefore not infallible; but in the more than one hundred and thirty years of its existence its decisions which have not withstood the questioning of criticism could almost be counted upon one hand. In it the people have the warrant of stability, of progress, and of humanity. Wherever there is a final authority it must be vested in mortal men. There has not been discovered a more worthy lodging-place for such authority than the Supreme Court of the United States.

Such is the legislative and judicial power that the people have established in their government. Recognizing the latent forces of the Constitution, which, in accordance with the spirit of the times, have been drawn on for the purpose of promoting the public welfare, it has been very seldom that the court has been compelled to find that any humanitarian legislation was beyond the power which the people had granted to the Congress. When such a decision has been made, as in the recent case of the child labor law, it does not mean that the court of nation wants child labor, but it simply means that the Congress has gone outside of the limitations prescribed for it by the people in their Constitution and attempted to legislate on a subject which the several States and the people themselves have chosen to keep under their own control.

Should the people desire to have the Congress pass laws relating to that over which they have not yet granted to it any jurisdiction, the way is open and plain to proceed in the same method that was taken in relation to income taxes, direct election of senators, equal suffrage, or prohibition—by an amendment to the Constitution.

One of the proposals for enlarging the present field of legislation has been to give the Congress authority to make valid a proposed law which the Supreme Court had declared was outside the authority granted by the people by the simple device of re-enacting it. Such a provision would make the Congress finally supreme. In the last resort its powers practically would be unlimited. This would be to do away with the great main principle of our written Constitution, which regards the people as sovereign and the government as their agent, and would tend to make the legislative body sovereign and the people its subjects. It would to an extent substitute for the will of the people, definitely and permanently expressed in their written Constitution, the changing and uncertain will of the Congress. That would radically alter our form of government and take from it its chief guarantee of freedom.

This enlarging magnitude of legislation, these continual proposals for changes under which laws might become very excessive, whether they result from the praiseworthy motive of promoting general reform or whether they reflect the raising of the general standard of human relationship, require a new attitude on the part of the people toward their government.’ Our country has adopted this course. The choice has been made. It could not withdraw now if it would. But it makes it necessary to guard against the dangers which arise from this new position. It makes it necessary to keep in mind the limitation of what can be accomplished by law. It makes it necessary to adopt a new vigilance. It is not sufficient to secure legislation of this nature and leave it to go alone. It cannot execute itself. Oftentimes it will not be competently administered without the assistance of vigorous support. There must not be permitted any substitution of private will for public authority. There is required a renewed and enlarged determination to secure the observance and enforcement of the law.

So long as the National Government confined itself to providing those fundamentals of liberty, order, and justice for which it was primarily established, its course was reasonably clear and plain. No large amount of revenue was required. No great swarms of public employees were necessary. There was little clash of special interests or different sections, and what there was of this nature consisted not of petty details but of broad principles. There was time for the consideration of great questions of policy. There was an opportunity for mature deliberation. What the government undertook to do it could perform with a fair degree of accuracy and precision.

But this has all been changed by embarking on a policy of a general exercise of police powers, by the public control of much private enterprise and private conduct, and of furnishing a public supply for much private need. Here are these enormous obligations which the people found they themselves were imperfectly discharging. They therefore undertook to lay their burdens on the National Government. Under this weight the former accuracy of administration breaks down. The government has not at its disposal a supply of ability, honesty, and character necessary for the solution of all these problems, or an executive capacity great enough for their perfect administration. Nor is it in the possession of a wisdom which enables it to take great enterprises and manage them with no ground for criticism. We cannot rid ourselves of the human element in our affairs by an act of legislation which places them under the jurisdiction of a public commission.

The same limit of the law is manifest in the exercise of the police authority. There can be no perfect control of personal conduct by national legislation. Its attempt must be accompanied with the full expectation of very many failures. The problem of preventing vice and crime and of restraining personal and organized selfishness is as old as human experience. We shall not find for it an immediate and complete solution in an amendment to the Federal Constitution, an act of Congress, or in the findings of a new board or commission. There is no magic in government not possessed by the public at large by which these things can be done. The people cannot divest themselves of their really great burdens by undertaking to provide that they shall hereafter be borne by the government.

When provision is made for far-reaching action by public authority, whether it be in the nature of an expenditure of a large sum from the Treasury or the participation in a great moral reform, it all means the imposing of large additional obligations upon the people. In the last resort it is the people who must respond. They are the military power, they are the financial power, they are the moral power of the government. There is and can be no other. When a broad rule of action is laid down by law it is they who must perform.

If this conclusion be sound it becomes necessary to avoid the danger of asking of the people more than they can do. The times are not without evidence of a deep seated discontent not confined to any one locality or walk of life but shared in generally by those who contribute by the toil of their hand and brain to the carrying on of American enterprise. This is not the muttering of agitators; it is the conviction of the intelligence, industry, and character of the nation. There is a state of alarm, however unwarranted, on the part of many people lest they be unable to maintain themselves in their present positions. There is an apparent fear of loss of wages, loss of profits, and loss of place. There is a discernible physical and nervous exhaustion which leaves the country with little elasticity to adjust itself to the strain of events.

As the standard of civilization rises there is necessity for a larger and larger outlay to maintain the cost of existence. As the activities of government increase, as it extends its field of operations, the initial tax which it requires becomes manifolded many times when it is finally paid by the ultimate consumer. When there is added to this aggravated financial condition an increasing amount of regulation and police control, the burden of it all be comes very great.

Behind very many of these enlarging activities lies the untenable theory that there is some short cut to perfection. It is conceived that there can be a horizontal elevation of the standards of the nation, immediate and perceptible, by the simple device of new laws. This has never been the case in human experience. Progress is slow and the result of a long and arduous process of self discipline. It is not conferred upon the people, it comes from the people. In a republic the law reflects rather than makes the standard of conduct and the state of public opinion. Real reform does not begin with a law, it ends with a law. The attempt to dragoon the body when the need is to convince the soul will end only in revolt.

The Coolidges at the Minnesota State Fair, September 1922.

Under the attempt to perform the impossible there sets in a general disintegration. When legislation fails, those who look upon it as a sovereign remedy simply cry out for more legislation. A sound and wise statesmanship which recognizes and attempts to abide by its limitations will undoubtedly find itself displaced by that type of public official who promises much, talks much, legislates much, expends much, but accomplishes little. The deliberate, sound judgment of the country is likely to find it has been superseded by a popular whim. The independence of the legislator is broken down. The enforcement of the law becomes uncertain. The courts fail in their function of speedy and accurate justice; their judgments are questioned and their independence is threatened. The law, changed and changeable on slight provocation, loses its sanctity and authority. A continuation of this condition opens the road to chaos.

These dangers must be recognized. These limits must be observed. Having embarked the government upon the enterprise of reform and regulation it must be realized that unaided and alone it can accomplish very little. It is only one element, and that not the most powerful in the promotion of progress. When it goes into this broad field it can furnish to the people only what the people furnish to it. Its measure of success is limited by the measure of their service.

This is very far from being a conclusion of discouragement. It is very far from being a conclusion that what legislation cannot do for the people they cannot do for themselves. The limit of what can be done by the law is soon reached, but the limit of what can be done by an aroused and vigorous citizenship has never been exhausted. In undertaking to bear these burdens and solve these problems the government needs the continuing indulgence, co-operation, and support of the people. When the public understands that there must be an increased and increasing effort, such effort will be forthcoming. They are not ignorant of the personal equation in the administration of their affairs. When trouble arises in any quarter they do not inquire what sort of a law they have there, but they inquire what sort of a governor and sheriff they have there. They will not long fail to observe that what kind of government they have depends upon what kind of citizens they have.

It is time to supplement the appeal to law, which is limited, with an appeal to the spirit of the people, which is unlimited. Some unsettlements disturb, but they are temporary. Some factious elements exist, but they are small. No assessment of the material conditions of Americans can warrant anything but the highest courage and the deepest faith. No reliance upon the national character has ever been betrayed. No survey which goes below the surface can fail to discover a solid and substantial foundation for satisfaction. But our countrymen must remember that they have, and can have, no dependence save themselves. Our institutions are their institutions. Our government is their government. Our laws are their laws. It is for them to enforce, support, and obey. If in this they fail, there are none who can succeed. The sanctity of duly constituted tribunals must be maintained. Undivided allegiance to public authority must be required. With a citizenship which voluntarily establishes and defends these, the cause of America is secure. Without that all else is of little avail.”

Some of the 100,000 gathered to hear President Coolidge dedicate the Liberty Memorial, November 11, 1926. Photo credit: National WWI Museum and Memorial.

3) Dedication of the Liberty Memorial, Kansas City, November 11, 1926, before 100,000 in attendance (full text)

Fellow Countrymen:

It is with a mingling of sentiments that we come to dedicate this memorial. Erected in memory of those who defended their homes and their freedom in the World War, it stands or service and all that service implies. Reverence for our dead, respect for our living, loyalty to our country, devotion to humanity, consecration to religion, all of these and much more is represented in this towering monument and its massive supports. It has not been raised to commemorate war and victory, but rather the results of war and victory, which are embodied in peace and liberty. In its impressive symbolism it pictures the story of that one increasing purpose declared by the poet to mark all the forces of the past which finally converge in the spirit of America in order that our country as “the heir of all the ages, in the foremost files of time,” may forever hold aloft the glowing hope of progress and peace to all humanity.

Five years ago it was my fortune to take part in a public service held on this very site when General Pershing, Admiral Beatty, Marshal Foch, General Diaz, and General Jacques, representing several of the allied countries in the war, in the presence of the American Legion convention, assisted in a normal beginning of this work which is now reaching its completion. To-day I return at the special request of the distinguished Senators from Missouri and Kansas, and on the invitation of your committee on arrangements, in order that I may place the official sanction of the National Government upon one of the most elaborate and impressive memorials that adorn our country. It comes as a fitting observance of this eighth anniversary of the signing of the armistice on November 11, 1918. In each recurring year this day will be set aside to revive memories and renew ideals. While it did not mark the end of the war, for the end is not yet, it marked a general subsidence of the armed conflict which for more than four years shook the very foundations of western civilization.

We have little need to inquire how that war began. Its day of carnage is done. Nothing is to be gained from criminations and recriminations. We are attempting to restore the world to a state of better understanding and emity. We can even leave to others the discussion of who won the war. It is enough for us to know that the side on which we fought was victorious. But we should never forget that we were asserting our rights and maintaining our ideals. That, at least, we shall demand as our place in history.

The energy and success with which our country conducted its military operations after it had once entered the war has now become a closed record of fame. The experience of this thriving city and these two adjoining States was representative of that of the country. Soon came the marshaling of the National Guard. From its existing units in Missouri and Kansas the foundation of the Thirty-fifth Division was laid. The Eighty-ninth Division was raised almost entirely in these two States. A portion of the Forty-second, known as the Rainbow Division, came from this city. The whole martial spirit of this neighborhood, which within a radius of 200 miles had furnished the famous Regiment of Missouri Volunteers, commanded by Col. John W. Doniphan when he made one of the most celebrated of marches to the conquest of Chihuahua in the Mexican War, reasserted itself as it had done in sixty-one and ninety-eight. While these divisions were serving with so much distinction on the battle fields of France their fellow citizens were supporting them with scarcely less distinction in patriotic efforts at home. They were furnishing money or Liberty loans, subscribing to the relief associations headed by the Red Cross, turning but munitions from the factories and rations from the fields. The whole community was inspired with a devotion to the cause of liberty. Returning at the end of the war, these divisions have increased their distinction by being represented in high places in civil life. From the Eighty-ninth came the great administrator and colonial governor, Maj. Gen. Leonard Wood, and from the Thirty-fifth Division came a distinguished son of Missouri, the present Secretary of War, Col. Dwight F. Davis.

Under no other flag are those who have served their country held in such high appreciation. It is, of course, impossible for the eyes of the Government to detect all individual cases of veterans requiring relief in every part of our land. But the Veterans’ Bureau is organized into departments and subdivisions, so that if any worthy person escapes their observation it is because the utmost care and attention could do no more. In the last eight years about $3,500,000,000 have been expended by the National Government for restoration, education, and relief. Nearly $3,200,000,000 have been pledged to accrue in future benefits to all veterans. Whenever they may be suffering from illness, whatever may be its cause, the doors of our hospitals are open to them without charge until they are restored to health. This is an indication of praise and reward which our country bestows upon its veterans. Our admiration is boundless. It is no mere idle form; it is no shadow without reality, but a solid and substantial effort rising into the dignity of a sacrifice made by all the people that they might in some degree recognize and recompense those who have served in time of national peril. All veterans should know this and appreciate it, and they do. All citizens should know it and be proud of it, and they are.

Considering the inspiring record of your soldiers in the field and the general attitude of appreciation which has been constantly reiterated by the whole Nation, it would be but natural to suppose that this mid-western country would give appropriate expression to the honor and devotion in which it holds those who served their country and the ideals for which they were contending. But the magnitude of this memorial, and the broad base of popular support on which it rests, can scarcely fail to excite national wonder and admiration. More than one person out of four in the entire population of this city responded to an appeal for funds, which gave pledges in excess of $2,000,000. It represents the high aspirations of this locality for ideals expressed in forms of beauty. We can not look upon it without seeing a reflection of all the freshness and vigor that marks the life of the broad expanse of the open country and the love of the sciences and the arts and the graces as expressed in the life of her growing towns. These results are not achieved without real sacrifice. They supply their own overpowering answer to those who charge out countrymen with a lack of appreciation for the finer things of life. Those who have observed such criticism can not fail to discover that it results in large part, from misunderstanding. But assuming it to be correct, I am of the firm conviction that there is more hope for the progress of true ideals in the modern world even from a nation newly rich than there is from a nation of chronically poor. Honest poverty is one thing, but lack of industry and character is quite another. While we do not need to boast of our prosperity, or vaunt our ability to accumulate wealth, I see no occasion to apologize for it. It is the expression of a commendable American spirit to live a life not merely devoted to luxurious ease, but to practical accomplishment. Nowhere is this better exemplified than in our great mid-continental basin. It is the spirit which dares, which has faith, and which succeeds. It is not confined to materialism, but lays hold on a higher life.

No one can doubt that our country was exalted and inspired by its war experience. It attained a conscious national unity which it never before possessed. That unity ought always to be cherished as one of our choicest possessions. In this broad land of ours there is enough for everybody. We ought not to regret our diversification, but rather rejoice in it. The seashore should not be distressed because it is not the inlands, and the fertile plains ought not to distracted because they are not the mountain tops. These differences which seem to separate us are not real. The products of the shore, the inlands, the plain, and the mountain reach into every home. This is all one country. It all belongs to us. It is all our America.

We had revealed to us in our time of peril not only the geographical unity of our country, but, what was of even more importance, the unity of the spirit of our people. They might speak with different tongues, come from most divergent quarters of the globe, but in the essentials of the hour they were moved by a common purpose, devoted to a common cause, and loyal to a common country. We should not permit that spirit which was such a source of strength in our time of trial to be dissipated in the more easy days of peace. We needed it then and we need it now. But we ought to maintain it, not so much because it is to our advantage as because it is just and human and right.

Our population is a composite of many different racial strains. All of them have their points of weakness; all of them have their points of strength. We shall not make the most progress by undertaking to rely upon the sufficiency of any one of them, but rather by using the combination of the power which can be derived from all of them. The policy which was adopted during the war of selective service through the compulsory Government intervention is the same policy which we should carry out in peace through voluntary personal action. Our armies could not be said to partake of any distinct racial characteristic; many of our soldiers were foreigners by birth, but they were all Americans in the defense of our common interests. There was ample opportunity for every nationality and every talent. The same condition should prevail in our peace-time social and economic organization. We recognize no artificial distinctions, no hereditary titles, but leave each individual free to assume and enjoy the rank to which his own services to society entitle him. This great lesson in democracy, this great example of equality which came to us as the experience of the war, ought never to be forgotten. It was a resurgence of the true American spirit which combined our people through a common purpose into one harmonious whole. When armistice day came in 1918, America had reached a higher and truer national spirit than it ever before possessed. We at last realized in a new vision that we were all one people.

Our country has never sought to be a military power. It cherishes no imperialistic designs, it is not infatuated with any vision of empire. It is content within its own territory, to prosper through the development of its own resources. But we realize thoroughly that no one will protect us unless we protect ourselves. Domestic peace and international security are among the first objects to be sought by any government. Without order under the protection of law there could be no liberty. To insure these necessary conditions we maintain a very moderate military establishment in proportion to our numbers and extent of territory. It is a menace to no one except the evildoer. It is a notice to everybody that the authority of our Government will be maintained and that we recognize that it is the first duty of Americans to look after America and maintain the supremacy of American rights. To adopt any other policy would be to invite disorder and aggression which must either be borne with humiliating submission or result in a declaration of war.

While of course our Government is thoroughly committed to a policy of permanent international peace and has made and will continue to make every reasonable effort in that direction, it is therefore also committed to a policy of adequate national defense. Like everything that has any value, the Army and Navy cost something. In the last half dozen years we have appropriated for their support about $4,000,000,000. Taken as a whole, there is no better Navy than our own in the world. If our Army is not as large as that of some other countries, it is not outmatched by any other like number of troops. Our entire military and naval forces represent a strength of about 550,000 men, altogether the largest which we have ever maintained in time of peace. We have recently laid out a five-year program for improving our aviation service. It is a mistake to suppose that our country is lagging behind in this modern art. Both in the excellence and speed of its planes it holds high records, while in number of miles covered in commercial and postal aviation it exceeds that of any other countries.

Although I have spoken of our national defenses somewhat in relation to other countries, I have done so entirely for the purpose of measurement and not for comparison, for our Government stands also thoroughly committed to the policy of avoiding competition in armaments. We expect to provide ourselves with reasonable protection, but we do not desire to enter into competition with any other country in the maintenance of land or sea forces. Such a course is always productive of suspicion and distrust, which usually results in inflicting upon the people an unnecessary burden of expense, and when carried to its logical conclusion ends in armed conflict. We have at last entered into treaties with the great powers eliminating to a large degree competition in naval armaments. We are engaged in negotiations to broaden and extend this humane and enlightened policy and are willing to make reasonable sacrifices to secure its further adoption.

It is doubtful if in the present circumstances of our country the subject of economy and the reduction of the war debt has ever been given sufficient prominence in considering the problem of national defense. For the conduct of military operations either by land or sea three elements are necessary. One is a question of personnel. We have a population which surpasses that of any of the great powers. Not only that, it is of a vigorous and prolific type, intelligent and courageous, capable of supplying many millions of men for active duty. Another relates to supplies. In our agriculture and our industry we could be not only well-nigh self-sustaining, but our production could be stimulated to reach an enormous amount. The last requirement, which is also of supreme importance, is a supply of money. It is difficult to estimate in figures the entire resources of our country and impossible to comprehend them. It is estimated to be approaching in value $400,000,000,000. No one could say in advance how large a sum could be secured from a system of war taxation, but everyone knows it would be insufficient to meet the cost of war. It would be necessary for the Treasury to resort to the use of the national credit. Great as that might be, it is limitless. To carry on the last conflict we borrowed in excess of $26,000,000,000. This great debt has been reduced to about $19,000,000,000. So long as that is unpaid it stands as a tremendous impediment against the ability of America to defend itself by military operations. Until this obligation is discharged it is the one insuperable obstacle to the possibility of developing our full national strength. Every time a Liberty bond is retired preparedness is advanced.

It is more and more becoming the conviction of students of adequate defense that in time of national peril the Government should be clothed with authority to call into its service all of its man power and all of its property under such terms and conditions that it may completely avoid making a sacrifice of one and a profiteer of another. To expose some men to the perils of the battle field while others are left to reap large gains from the distress of their country is not in harmony with our ideal of equality. Any future policy of conscription should be all-inclusive, applicable in its terms to the entire personnel and the entire wealth of the whole Nation.

It is often said that we profited from the World War. We did not profit from it but lost from it in common with all countries engaged in it. Some individuals made gains, but the Nation suffered great losses. Merely in the matter of our national debt it will require heavy sacrifices extended over a period of about 30 years to recoup those losses. What we suffered indirectly in the diminution of our commerce and through the deflation which occurred when we had to terminate the expenditure of our capital and begin to live on our income is a vast sum which can never be estimated. The war left us with debts and mortgages, without counting our obligations to our veterans, which it will take a generation to discharge. High taxes, insolvent banks, ruined industry, distressed agriculture – all followed in its train. While the period of liquidation appears to have been passed, long years of laborious toil on the part of the people will be necessary to repair our loss. It was not because our resources had not been impaired, but because they were so great that we could meantime finance these losses while they are being restored, that we have been able so early to revive our prosperity. But the money which we are making to-day has to be used in part to replace that which we expended during the war.

In time the damage can be repaired, but there are irreparable losses which will go on forever. We see them in the vacant home, in the orphaned children, in the widowed women, in the bereaved parents. To the thousands of the youth who are gone forever must be added other thousands of maimed and disabled. It is these things that bring to us more emphatically than anything else the bitterness, the suffering, and the devastation of armed conflict.

It is not only because of these enormous losses suffered alike by ourselves and the rest of the world that we desire peace, but because we look to the arts of peace rather than war as the means by which mankind will finally develop its greatest spiritual power. We know that discipline comes only from effort and sacrifice. We know that character can result only from toil and suffering. We recognize the courage, the loyalty, and the devotion that are displayed in war, and we realize that we must hold many things more precious than life itself.

‘Tis man’s perdition to be safe

When for the truth he ought to die.

But it can not be that the final development of all these fine qualities is dependent upon slaughter and carnage and death. There must be a better, purer process within the realm of peace where humanity can discipline itself, develop its courage, replenish its faith, and perfect its character. In the true service of that ideal, which is even more difficult to maintain than our present standards, it can not be that there would be any lack of opportunity for the revelation of the highest form of spiritual life.

We shall not be able to cultivate the arts of peace by constant appeal to primal instincts. To the people of the jungle, the stranger was always the enemy. As the race grew up through the family, the tribe, the clan, and the nation, this sentiment always survived. The foreigner was subject to suspicion, without rights and without friends. This spirit prevailed even under the Roman Empire. It would not have been sufficient for St. Paul to claim protection because he was a human being, or even an inhabitant of a peaceful province. It was only when he asserted that he was a Roman citizen that he could claim any rights or the protection of any laws. We do not easily emancipate ourselves from these age-old traditions. When we come in contact with people differing from ourselves in dress and appearance, in speech and accent, the inherited habits of our physical being naturally react unfavorably. Nothing is easier than an appeal to suspicion and distrust. It is always certain that the unthinking will respond to such efforts. But such reaction is of the flesh, not of the spirit. It represents the opportunist, not the idealist. It serves the imperialistic cause of conquest, but it is not found in the lesson of the Sermon on the Mount. It may flourish as the impulse of the day, but it is not the standard which will finally prevail in the world. It is necessary that the statesmanship of peace should lead in some other direction.

If we are to have peace, therefore, we are to live in accordance with the dictates of a higher life. We shall avoid any national spirit of suspicion, distrust, and hatred toward other nations. The Old World has for generations indulged itself in this form of luxury. The results have been ruinous. It is not for us who are more fortunately circumstanced to pass judgment upon those who are less favored. In their place we might have done worse. But it is our duty to be warned by their example and to take full advantage of our own position. We want understanding, good will, and friendly relations between ourselves and all other people. The first requisite for this purpose is a friendly attitude on our own part. They tell us that we are not liked in Europe. Such reports are undoubtedly exaggerated and can be given altogether too much importance. We are a creditor Nation. We are more prosperous than some others. This means that our interests have come within the European circle where distrust and suspicion, if nothing more, have been altogether too common. To turn such attention to us indicates at least that we are not ignored.

While we can assume no responsibility for the opinions of others, we are responsible for our own sentiments. We ought to be wise enough to know that in the sober and informed thought of other countries we probably hold the place of a favored nation. We ought not to fail to appreciate the trials and difficulties, the suffering and the sacrifices of the people of our sister nations, and to extend to them at all times our patience, our sympathy, and such help as we believe will enable them to be restored to a sound and prosperous condition. I want to be sure that the attitude and acts of the American Government are right. I am willing to entrust to others the full responsibility for the results of their own behavior.

The Coolidges at the White House, just outside the West Wing offices, 1926.

Our Government has steadily maintained the policy of the recognition and sanctity of international obligations and the performance of international covenants. It has not believed that the world, economically, financially, or morally, could rest upon any other secure foundation. But such a policy does not include extortion or oppression. Moderation is a mutual international obligation. We have therefore undertaken to deal with other countries in accordance with these principles, believing that their application is for the welfare of the world and the advancement of civilization.

In our prosperity and financial resources we have seen not only our own advantage but an increasing advantage to other people who have needed our assistance. The fact that our position is strong, our finances stable, our trade large, has steadied and supported the economic condition of the whole world. Those who need credit ought not to complain, but rather rejoice that there is a bank able to serve their needs. We have maintained our detached and independent position in order that we might be better prepared, in our own way, to serve those who need our help. We have not desired our sought to intrude, but to give our counsel and our assistance when it has been asked. Our influence is none the less valuable because we have insisted that it should not be used by one country against another, but for the fair and disinterested service of all. We have signified our willingness to cooperate with other countries to secure a method for the settlement of disputes according to the dictates of reason.

Justice is an ideal, whether it be applied between man and man or between nation and nation. Ideals are not secured without corresponding sacrifice. Justice can not be secured without the maintenance and support of institutions for its administration. We have provided courts through which it might be administered in the case of our individual citizens. A Permanent Court of International Justice has been established to which nations may voluntarily resort for an adjudication of their differences. It has been subject to much misrepresentation, which has resulted in much misconception of its principles and objects among our people. I have advocated adherence to such a court by this Nation on condition that the statute or treaty creating it be amended to meet our views. The Senate has adopted a resolution for that purpose.

While the nations involved can not yet be said to have made a final determination, and from most of them no answer has been received, many of them have indicated that they are unwilling to concur in the conditions adopted by the resolution of the Senate. While no final decision can be made by our Government until final answers are received, the situation has been sufficiently developed so that I feel warranted in saying that I do not intend to ask the Senate to modify its position. I do not believe the Senate would take favorable action on any such proposal, and unless the requirements of the Senate resolution are met by the other interested nations I can see no prospect of this country adhering to the court.

While we recognize the obligations arising from the war and the common dictates of humanity which ever bind us to a friendly consideration for other people, our main responsibility is for America. In the present state of the world that responsibility is more grave than it ever was at any other time. We have to face the facts. The margin of safety in human affairs is never very broad, as we have seen from the experience of the last dozen years. If the American spirit fails, what hope has the world? In the hour of our triumph and power we can not escape the need for sober thought and consecrated action. These dead whom we here commemorate have placed their trust in us. Their living comrades have made their sacrifice in the belief that we would not fail. In the consciousness of that trust and that belief this memorial stands as our pledge to their faith, a holy testament that our country will continue to do its duty under the guidance of a Divine Providence.”