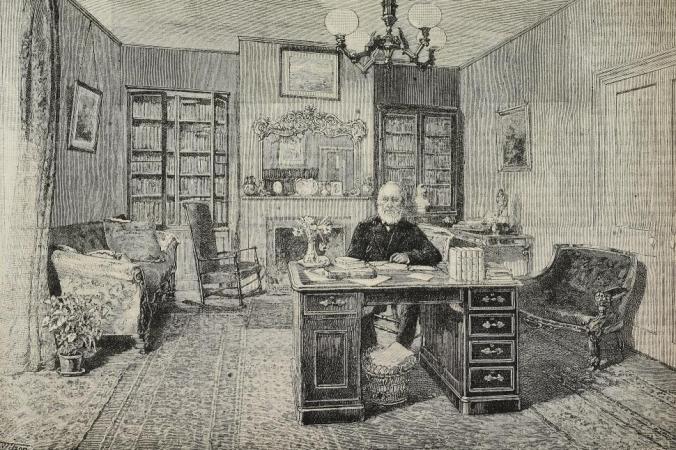

John Greenleaf Whittier in his study at Amesbury, engraving from The Illustrated London News, No 2787, September 17, 1892. Photo credit: DEA / ICAS94 / Getty Images.

The vandalism, back in mid-June, of John Greenleaf Whittier’s statue in the California city that bears his name is yet another profoundly ironic and sadly misplaced affront to history’s worthy examples and advocates of genuine justice. The statues of General Grant and Francis Scott Key in San Francisco among others around the country make more than an isolated crusade of ignorance. They are now a destructive pattern of what happens when ignorance runs rampant. Vandalism is fast overtaking those historical figures who were, in life, the most tolerant champions of fair dealing and faithful allies in the fight for that day when shackles would be broken not only on millions enslaved in body but for millions more enslaved in mind, heart, and soul. In an era of many luminaries of all kinds (the nineteenth century), few were as resolute and steadfast when it came to the end of slavery and the advance of justice between all races as the poet John Greenleaf Whittier.

While it may be symptomatic of the failures in education, descending as they do too often into poorly informed activism, it is much more a demonstration of taking the cultural wrecking ball to everything and everyone — even the best — with no discernment for good or bad in the wreckage. When we remove the best friends of justice, we can expect only deeper, more insidious injustice to follow. Ditching or defacing those with courage and conviction for commendable reasons in the past will hardly inspire more courage or conviction on behalf of causes which deserve them in our time let alone for future generations. We are left in the terrifying position of having enabled fear not fortitude, moral cowardice not moral courage, and ultimately, more exploitation by those who appropriate even the greatest symbols of good to control others instead of liberate minds and free lives.

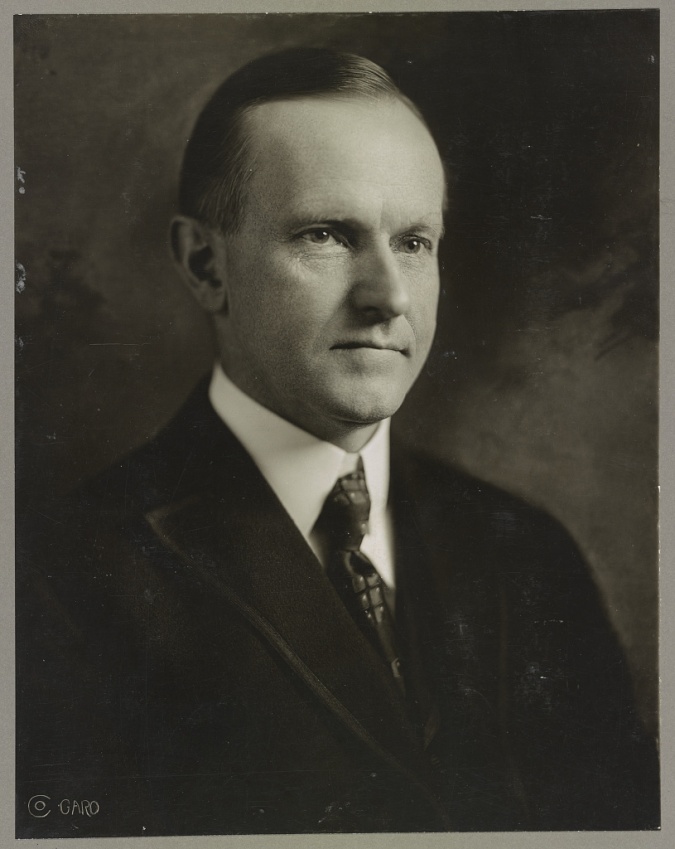

Whittier, furthermore, inspired countless readers to defy the “way things are” as the way they should be. He urged others not to be fooled by the moral contortions of what people rationalize and justify as the equivalent of what is right and praiseworthy. He did all this without telegraphing his righteousness but by living with the humility he preached, the tolerance he praised, and the decency he cherished for everyone. Among those he inspired was President Calvin Coolidge, who committed his poetry to memory but also revered his home as the site of a truly great muse, a fountainhead of brave deeds and needed ideals.

You better get a copy of Whittier and read Snowbound before you go there [Whittier’s old home in Amesbury, Massachusetts]. It is fine piece of work and it is the piece that brought Whittier into prominent notice. You will see there the old home in which he was living the time that the theme of Snowbound took place… — Coolidge, press conference, June 23, 1925

So, before we throw out another moral hero and deserving friend with the too often irrational, emotionally-laden charge of “racist,” we would do well to look up the name and join not only Coolidge in the revolutionary task of opening our minds but also Whittier in matching them with our actions.

Calvin Coolidge, Boston (1920). Photo credit: John H. Garo studio.