“Signing the Mayflower Compact” by Jean Leon Gerome Ferris (1899)

How far the people of the Commonwealth has advanced between 1620 and the days of the Revolution is indicated by the difference between the Mayflower Compact and the Declaration of Rights and the Frame of Government, which is the title of the Constitution adopted in 1780. The Declaration sets out with great precision the fundamental principles of liberty established by law.

Article I declares that all men are born free and equal.

Article II guarantees religious freedom.

Article X asserts the right of protection of life, liberty, and property by the government, and as a corollary the necessity of serving and supporting the government.

Article XVIII enjoins “a constant adherence to piety, justice, moderation, temperance, industry, and frugality” as necessary to preserve liberty and maintain a free government.

Article XXIX proclaims “the right of every citizen to be tried by judges as free, impartial, and independent as the lot of humanity will admit.”

Article XXX decrees a complete separation of the legislative, executive, and judicial departments, “to the end that it may be a government of laws and not of men.”

In between is asserted the sovereignty of the people, the liberty of speech and of the press, the right of trial by jury, and the duty of providing education, together with the other guarantees of freedom.

Mural of John Adams, Samuel Adams, and James Bowdoin laboring over the drafting of the Massachusetts constitution adopted in 1780 through the votes of town meetings. Its vision and quality are attested by the fact that it became one of the oldest working constitutions in the world. It would exercise a significant influence on the form of the U. S. Constitution seven years later.

We have come to think of all these principles as natural and self-evident. It is well to remember that we are in the enjoyment of them by reason of age-old effort and the constant sacrifice of treasure and blood finally wrought into standing law. There is no other process by which they can be maintained.

All of this has been the inevitable outcome of the belief of the Puritans in the rights of the individual. This required education, and the first public school was opened in Boston in 1635.

In 1647 the general court enjoined each town of fifty householders to have a primary school, and each of one hundred families a grammar-school.

In 1839 a State Normal School was opened, and Massachusetts was the first to have a State Board of Education.

The same ideal that educated the mind protected the health and regulated industrial conditions. In 1836 the first Child Labor Law was passed. In 1842 combinations of workmen made for the purpose of improving their conditions were declared lawful. In 1867 factory inspection was begun. The year 1869 saw the first Railroad Commission and the beginnings of a State Board of Arbitration. It was here that there was established the first State Board of Health, the first State Board of Charities, the first State Department of Insurance, the first Minimum Wage Law for women and children, and the first State sanatorium for the treatment of tuberculosis.

Monument to the now rare but once immensely popular Baldwin apple developed by Colonel Loammi Baldwin.

Ephraim Wales Bull, who developed the Concord grape from wild vines that flourished in his backyard at Concord, 1849.

Dr. Thomas Welch, dentist and inventor, with his wife and son, devised the concept of non-fermented grape juice by the then new process of pasteurization of the containers and thus preventing the natural fermentation from juice to wine.

Massachusetts has been the location of a an enormous industrial development. It is claimed that the first agricultural show was held there. Certainly it was the home of the Baldwin apple and the Concord grape. There the first railroad was built.

Four inventions, most important in modern life, are represented by the telephone, which Bell invented there, the telegraph, the sewing-machine, and the cotton-gin of Morse, Howe, and Whitney, three of her native sons, while inoculation was first used there by Boylston, and the first practical demonstration of the discovery of ether was made in one of her hospitals…

Alexander Graham Bell and Thomas Watson began their experiments in sound to help the deaf, which included Bell’s mother and wife.

Samuel B. Morse with his telegraph, bequeathing not only “What hath God wrought” to the world but also his universal code and the first international communications line.

Elias Howe revolutionized the manufacture of clothes with the invention that saved millions the hours of slow, painstaking hand-work with thread and needle. Photo credit: doggedlyyours.com

Eli Whitney discovered the means of mechanizing cotton processing and thereby fired the first shot across the bow for freeing manual labor from lives of back-breaking slavery.

Zabdiel Boylston (1679-1766) stands as one of the earliest physicians in America, not only the first to perform successful surgery but also the first to perform inoculations. His work, learned with the help of Cotton Mather and the freed slave named Onesimus, spared countless lives in the Boston smallpox epidemics of 1721 and later.

Massachusetts has contributed men of great eminence to all the learned professions. Jonathan Edwards preached there, Benjamin Franklin was born there. It has had such scientists as Agassiz and Gray, such preachers as Channing, Parker, Brooks, and Moody.

The great Congregationalist minister and theologian, Jonathan Edwards, who served for a time at Northampton, later distinguished as Coolidge’s adopted hometown.

Benjamin Franklin, “First American,” originally born in Boston.

Louis Agassiz, Swiss-born geologist, noted for his work on glaciers, along with more controversial contributions to scientific thought.. Agassiz chose Massachusetts to do much of his work.

Asa Gray, respected friend of Darwin, considered one of the foremost botanists of the nineteenth century.

Unitarian preacher, William Ellery Channing, depicted at the Boston Public Garden.

Thomas Parker (1595-1677), noncomformist preacher, founder of Newbury, taught for free at Harvard, considered by Cotton Mather “one of the greatest scholars” of English history.

Phillips Brooks, composer of “O Little Town of Bethlehem,” is here honored delivering, in characteristic zeal, one of his countless sermons, studies that are still read and analyzed today.

Dwight L. Moody addressing just a few of the thousands upon thousands his preaching and life’s work touched across the spectrum.

In literature it carries such names as Emerson, Hawthorne, Holmes, Longfellow, Lowell, Whittier, Everett, Phillips, and Julia Ward Howe; in art Sargent, Whistler, Stuart, Bulfinch, Copley, and Hunt; among its lawyers are Story, Cushing, Shaw, Choate, Webster, and Parsons.

Ralph Waldo Emerson, trancendentalist and leading light in Boston’s literary circle.

Nathaniel Hawthorne, friend of the tragic Franklin Pierce and iconic New Englander.

Dr. Oliver Wendell Holmes, Sr., father of the Supreme Court Justice and preeminent influence in his own right.

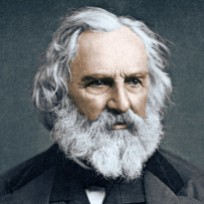

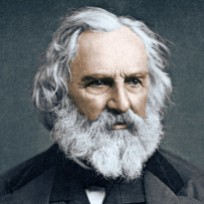

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, perhaps best known for “The Midnight Ride of Paul Revere.”

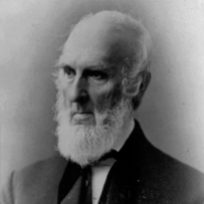

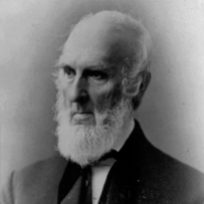

James Russell Lowell, native of Cambridge (Massachusetts), Romantic poet and literary critic, part of the Fireside Poets, friend of Longfellow and the Boston circle of authors.

John Greenleaf Whittier, poet, abolitionist and reformer, one of the firmest friends of civil rights

Wendell Phillips, fearless challenger of the status quo, activist for rights of Native Americans and slaves, Phillips relinquished what could have been a high social standing for his convictions.

Edward Everett, superlative orator, diplomat, public servant, the better known speaker at Gettysburg who delivered the less memorable speech there preceding Lincoln’s, Everett was a stalwart advocate for responsible public service and honorable, engaged civic participation by all.

Julia Ward Howe, author, activist, and composer of the lyrics of “The Battle Hymn of the Republic.”

John Singer Sargent, born abroad, lived outside of the country for much of his professional life yet left indelible impressions on art and his era.

James Abbott McNeil Whistler, born in Lowell, best known for the depiction of his mother Anna in paint, substituting for an absent sitter that became one of the most iconic paintings of the era.

Gilbert Stuart, self portrait from 1778, perhaps the most prolific of painters from the American founding, completing portraits not only of six Presidents but hundreds of others, better and lesser known figures contemporary with them.

Charles Bulfinch, native of Boston, architect whose mark on design covers not only Massachusetts but early national buildings and structures too. Bulfinch would go on to serve as the Architect of the Capitol, 1818-1829

John Singleton Copley, likely born in Boston, would leave America for London in 1774 and never return but still stands at the heights of artistic talent, capturing countless glimpses into the lives of the colonial era, across the social spectrum.

William Morris Hunt in 1879, native of Vermont but adopted son of Massachusetts – like Coolidge himself – who left his impact on art well beyond his own work in oils, lithography, and sculpting but upon the profound improvement of artistry in the United States. Not many artists come to enjoy the level of influence Hunt possessed on the craft and its practitioners. It was Hunt who taught countless contemporaries, some equally or even better known than he, but few attain to Hunt’s role in bringing together a caliber of work the equal of any established master in the Old World. His influence was not and cannot be escaped.

Associate Justice Joseph Story, appointed by President Madison, author of a still much studied Commentary on the Constitution, remained a leading force on the Marshall Court.

Associate Justice William Cushing, one of the original members of the Supreme Court. Cushing served one of the longest tenures in those early years and left not only a legacy of decisions but also a strong administrative influence in those formative years.

In a portrait by William Morris Hunt, Lemuel Shaw, Chief Justice of the Massachusetts Supreme Court, shaped law in significant ways not only at the state but federal level through his solidly crafted and carefully reasoned decisions.

Rufus Choate, involved in many of the most important legal and policy decisions of the antebellum era, a Senator of Massachusetts and state attorney general, Choate was there at nearly every important question before the state and nation in those years.

“Black Dan” Webster, though a son of New Hampshire, he represented Massachusetts for many years and served as Secretary of State during some of the most difficult tests for America leading up to the War of 1861-65. Never a President, though he like Clay and Calhoun aspired to be, Webster was a preeminent champion of the bar and yet paid dearly for his political decisions over the years.

The Parson family of New England had long enjoyed a host of competent jurists and civic leaders, including Samuel Holden Parsons (1737-1789), who left New England to bring law to the frontier. Theophilus Parsons (1750-1813), and son of the same name both distinguished themselves in vital questions of public law and citizenship. It was Theophilus Sr., however, who demonstrates that very important decisions often trace their source to now unfortunately forgotten leaders. It was Judge Parsons whose persuasion of Sam Adams and John Hancock in a series of articles written by him that led to the adoption of the Federal Constitution by Massachusetts, overcoming very well-placed opposition. Great events often turn on small deeds.

Among its statesmen have been the Adamses, Webster, Sumner, Wilson, and Hoar. It has been the abiding-place of strong common sense, illustrated by Samuel Adams, master of the town meeting, and Jonathan Smith, the farmer from Lanesboro, who with Adams swung a hostile convention to the ratification of the Federal Constitution. Another clergyman, from Ipswich, was Manasseh Cutler, who drafted the Ordinance of 1787 which Representative Dane of Beverly presented to Congress, thus dedicating a sufficient area to freedom to insure the ultimate extinction of human slavery.

John Adams, 2nd President of the United States, instrumental through every major stage of the fight for independence from Great Britain to the standing of the United States as their own nation.

Samuel Adams, the Boston firebrand perhaps more than any other hated by Lord North’s government. Here Adams points to the Massachusetts Charter for protection of popular rights.

Charles Sumner, perhaps best known for the beating he sustained on the floor of Congress by Preston Brooks in 1856, sits here with friend Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. The wounds did not weaken his resolve to end slavery.

Henry Wilson, Vice President in the first Grant administration, likewise stood vehemently opposed to slavery’s perpetuation in the States.

George F. Hoar. a grandson of signer Roger Sherman, through a long career in public service fought repeatedly against the abuse of Native American rights, Chinese exclusion, women’s suffrage and the oppression of civil rights wherever it occurred. An unapologetic critic of imperial expansion in the nineteenth century, Hoar was unafraid who it may alienate and frequently got ahead of his own party in standing for those treated unjustly whether at home or abroad.

Jonathan Smith’s convincing stand at the ratification convention in 1788 prompted him to light a bonfire atop “Constitution Hill” (as he renamed “Bald Hill”) following the vote by Massachusetts to adopt the U. S. Constitution.

Manasseh Cutler (1742-1823) was the principal draftsman of the Northwest Ordinance of 1787 which outlined the basis for future state admission and organization. He is justifiably known as the “Father of Ohio University,” placing due emphasis on his work to advance education in the future country. It would be in a full and sound education that future generations would advance the ideals fought for in the Revolution and vanquish the narrow-minded prejudices and bigotry of past experience.

It was Nathan Dane of Ipswich who proposed the amendment to the Northwest Ordinance that prohibited slavery there and thus struck a critical blow to the eventual defeat of the institution.

The Commonwealth has furnished pioneers who have gone everywhere. They are represented by such men as General Rufus Putnam, who planned the settlement of southern Ohio; Marshall Field, the great merchant of Chicago; the five students of Williams College who laid the foundation of American foreign missions at the memorable haystack prayer-meeting; Peter Parker, who established the first hospital in China; while in another field of pioneering were Garrison, the abolitionist; Clara Barton, who founded the Red Cross; Mary Lyon, who led the way at Mount Holyoke to higher education of women; Horace Mann, who was foremost in the training of teachers for the public schools.

Rufus Putnam, soldier and surveyor, founding father of the Northwest Territory and pioneer of Ohio.

The iconic clock of Marshall Field’s beloved department store in Chicago.

Marshall Field had a vision to provide not only affordable goods but far more than that, a service of excellence. He would turn his resources to the betterment of the “Windy City” in a Museum of Natural History, the University of Chicago and countless other ways.

The Haystack Monument commemorating the 1806 meeting of Samuel Mills, James Richards, Francis LeBaron Robbins, Harvey Loomis, and Byram Green, in the midst of a lightning storm, that launched foreign missions on a scale not before undertaken for generations. Full of conviction for the Gospel and its power to change lives everywhere, these five are still changing the world through Christ.

Dr. Peter Parker (1804-1888) brought his heart for the Chinese and his knowledge of opthamology to serve, not be served. Chinese artist Lam Qua painted this portrait.

William Lloyd Garrison, driven to not merely phase out slavery but eradicate it from the roots up inflamed more than generation with the zeal to transform society by shaking the world by the scruff of the neck from its complacency and apathy. Garrison had no tolerance for “comfort zones.”

Clara Barton’s work, inspired by Florence Nightingale during the Crimean War, sparked the truly international movement for ministering to the wounded and broken — not just in body but in mind and soul.

Mary Lyon of Buckland (1797-1849), realized early the need for equipping women with the education and practical training that work its wholesome and good work upon the poorest, least among us. Founding Wheaton and Mount Holyoke, she poured that foundation on which countless women have gone out and been lights in the world.

Horace Mann (1796-1859), perhaps more than any other, set the basis for universal public education. Raised poor, Mann resolved not to see others around him struggle to rise out of ignorance and poverty when education could be improved not only to be better citizens but better people.

For more than three hundred years there has gone out an influence from Massachusetts that has touched all shores, influenced all modes of thought, and modified all governments. How broad it has been is disclosed when it is remembered that Garfield and Lincoln came of Massachusetts stock.

It was Edward Garfield who first stepped off the boat from England and arrived in Massachusetts c. 1630. The family tree grew from these and other New England roots to reach Ohio, that favored ground of Massachusetts natives to yield one of the most brilliant and studious men ever to reach the Presidency.

Descended from Samuel Lincoln (1622-1690), who arrived in Hingham, Massachusetts, in 1634, the President’s family made its beginnings in America through the Bay State.

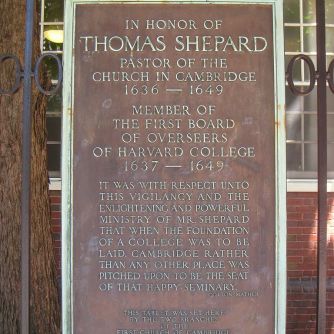

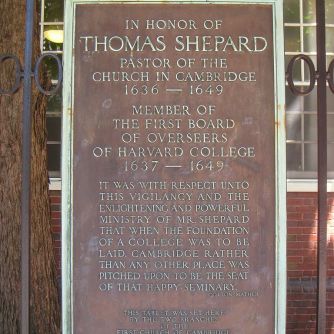

From the earliest days the people have exhibited a high capacity both for civil and religious government…What an important influence the churches and clergymen were in this early life is apparent wherever we turn. To Robinson, who remained at home, were joined others equally prominent who led their flocks to these shores. As Hooker, the early clergyman of Cambridge who, passing on with his congregation to Hartford, set the inextinguishable mark of freedom and local independence under the representative system upon government, so Shepard, who succeeded to his pulpit and was one of the committee of six magistrates and six clergymen chosen to establish the college, set the same inextinguishable mark upon education. It was in their town that the first book ever printed in America came from the press. Wherever a town meeting is held, wherever a legislature convenes, wherever a schoolhouse is opened, the moral power of these two men is felt. The Puritan was ever intent upon supporting democracy by learning, and the authority of the State by righteousness…

Plaque in Leyden honoring the Puritan minister who remained behind but prayerfully sent off those who would later arrive at Cape Cod aboard the Mayflower.

Thomas Hooker leads the settlement of Connecticut. Here they pray together, thanking God for His provision and mercy.

Thomas Hooker, minister-statesman, author of the first constitution for Connecticut, the Fundamental Orders providing a democratic system of representative government, where citizenship was not merely a bundle of rights but an interlocking framework of duties and obligations to God and each other.

![Harvard_College_Seal "For Christ and Church," now replaced by VERITAS ['truth'].](https://crackerpilgrim.files.wordpress.com/2020/06/harvard_college_seal.png?w=334&resize=334%2C334&h=334#038;h=334&crop=1)

“For Christ and Church,” now replaced by VERITAS [‘truth’].

Harvard University as depicted by Paul Revere in 1767.

Thomas Shepard, whose work at Cambridge, Massachusetts, proved instrumental in the founding of Harvard University in that town in 1636. Its original motto “For Christ and Church” encapsulated the visions of Shepard and its founders partnering ministers and the General Court of Massachusetts.

While there has come to the sons of the Puritans that progress which results from science and great material resources, their supreme choice is still made in favor of a greater power. The Supreme Judicial Court of Massachusetts, which enjoys a reputation for sound opinions and which makes its decisions more often cited than those of any other court, save the Supreme Court of the United States, recently announced the faith that is dominant still. “Mere intellectual power,” the decision runs, “and scientific achievement without uprightness of character may be more harmful than ignorance. Highly trained intelligence, combined with disregard of fundamental virtues, is a menace.” Above all else, the people still put their faith in character.

They do not suppose that all virtue landed at Plymouth Rock, that all patriotism defended Bunker Hill. From every people and from every faith there have come Puritans. Every town and countryside has bred devoted patriots…In that faith Massachusetts still lives.

— Calvin Coolidge, excerpts of address “Massachusetts and the Nation” delivered before the National Geographic Society meeting at Washington, February 2, 1923

The National Monument to the Forefathers, Plymouth, Massachusetts, designed by Boston artist and designer Hammatt Billings, who drew the original illustrations for Uncle Tom’s Cabin, stands in Plymouth, Massachusetts. Here President and Mrs. Coolidge look up at the enormous 81-foot granite structure dedicated almost 40 years before. Since 1989 the back panel has been inscribed with lines from Governor William Bradford’s account, Of Plymouth Plantation: “Thus out of small beginnings greater things have been produced by His hand that made all things of nothing and gives being to all things that are; and as one small candle may light a thousand, so the light here kindled hath shone unto many, yea in some sort to our whole nation; let the glorious name of Jehovah have all praise.”

![Harvard_College_Seal "For Christ and Church," now replaced by VERITAS ['truth'].](https://crackerpilgrim.files.wordpress.com/2020/06/harvard_college_seal.png?w=334&resize=334%2C334&h=334#038;h=334&crop=1)