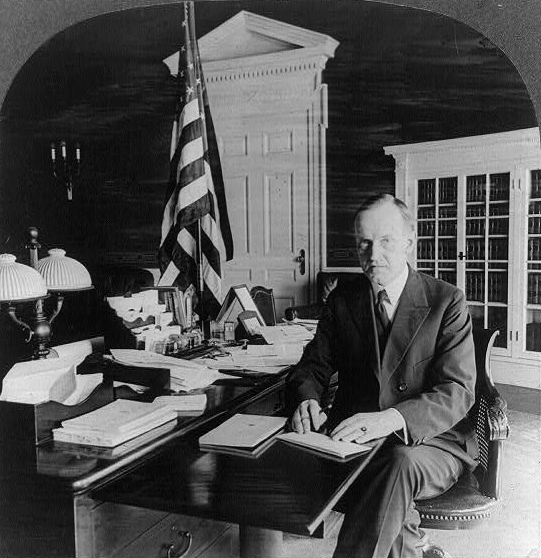

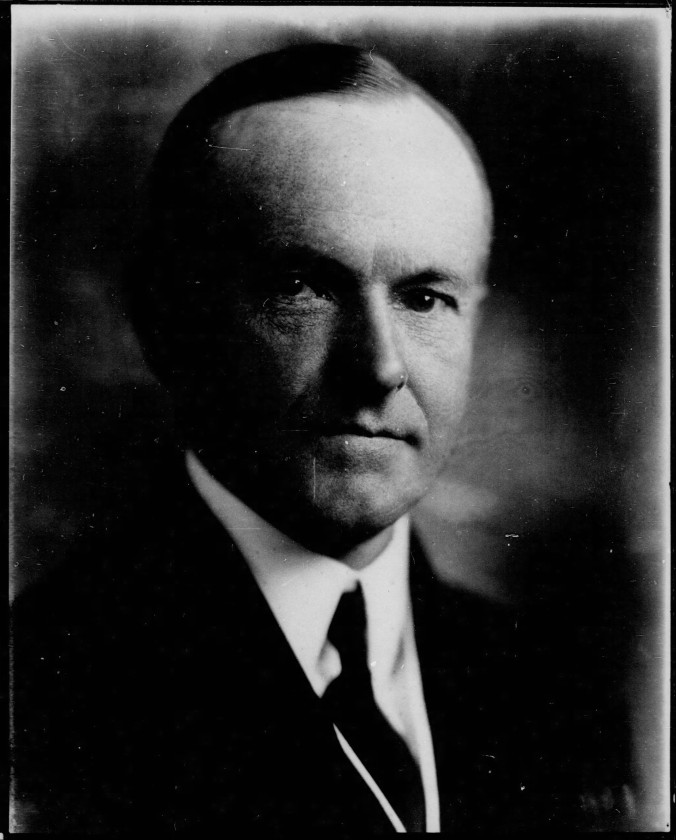

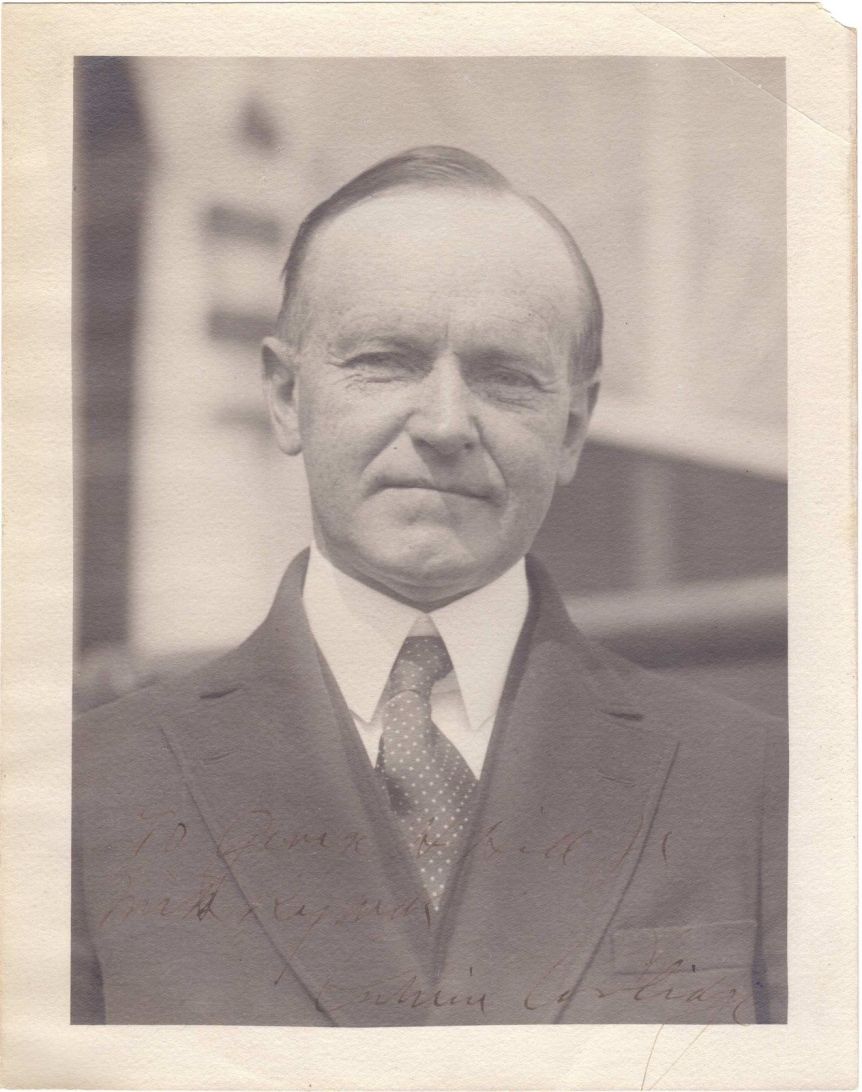

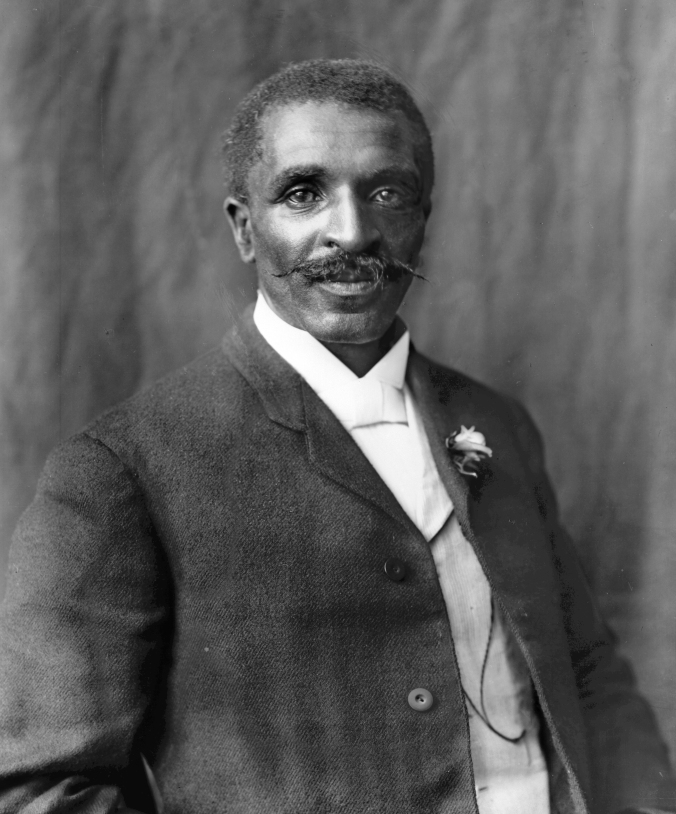

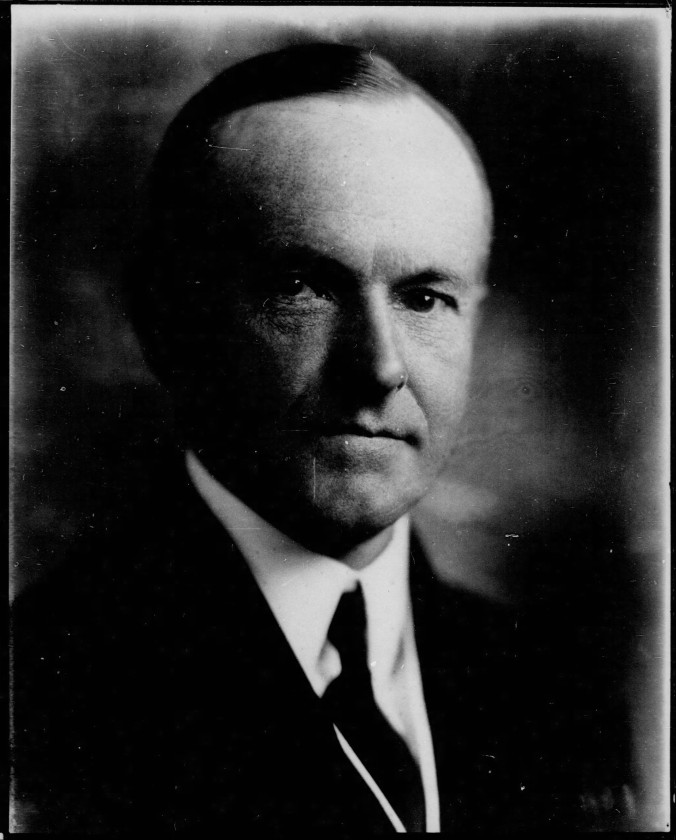

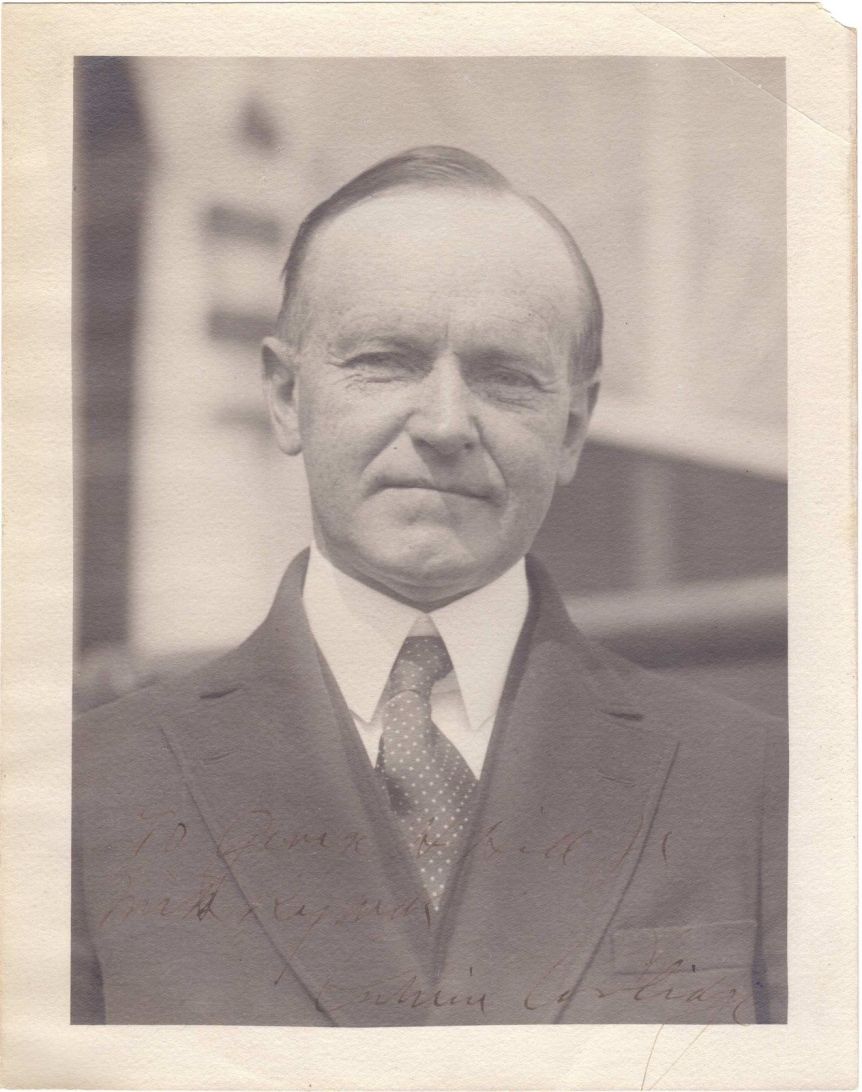

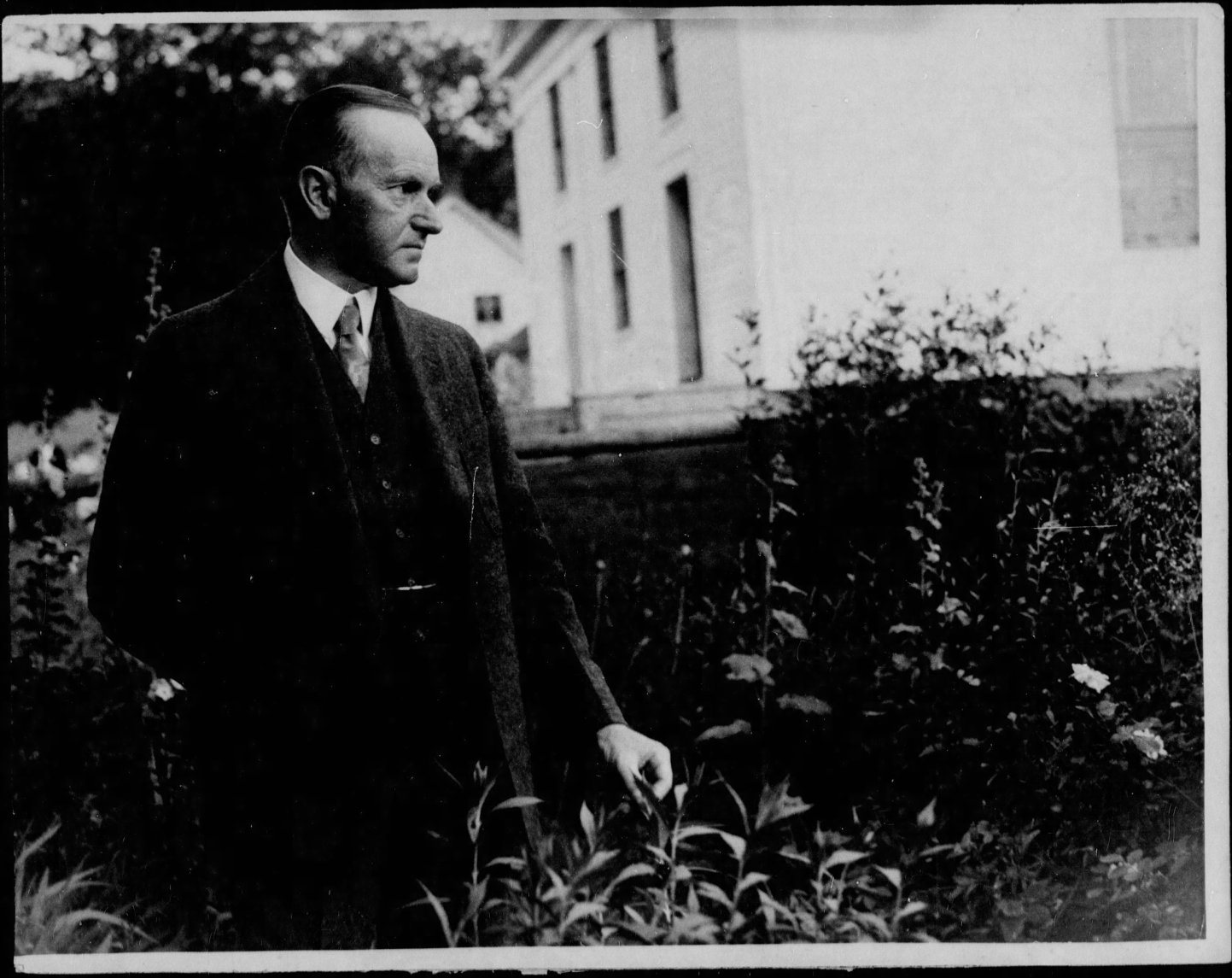

The movie hit Boston theaters on April 10, 1915. Adapted from Thomas Dixon’s novel, The Klansman, D. W. Griffith’s “Birth of a Nation” met opposition immediately for its overtly racist slant of history, lionizing the Klan while vilifying the “undesired” elements in American society. It had already been shown and endorsed by President Wilson at the White House. Wilson had praised Griffith’s movie as “writing history with lightning. My only regret is that it’s true.” But it was not true. It was quickly becoming officially validated historical revisionism, neatly packaged pro-Klan propaganda. The fight was on to prevent so bigoted a film from gaining further cultural and official affirmation. William M. Trotter, editor of the Boston Guardian, zealously led much of the effort to petition Governor Walsh and the General Court to strengthen the law for its censorship. As the battle moved into the State House, something curious and unusual happened. Changing the rule for censorship from a simple majority to total unanimity, the House sent the bill to the Senate fully anticipating the upper chamber to go along and effectively kill censorship of the film in its tracks. When the bill came back to the Senate for reconsideration however, they had not considered with whom they were dealing in the person of the Senate President, Calvin Coolidge.

As the presiding officer of the Senate, no vote is normally exercised in legislative business. A tie means that a bill dies on the floor, thwarting the attempt by the House, on this occasion, from raising a virtually insurmountable threshold in favor of showing the movie. Senator Coolidge could have let this one go by, do nothing and sit silently as the Senate approved the lower chamber’s amended bill, giving a green light to the showing of Griffith’s movie. Instead, as Trotter, Boston papers and “colored” Americans from Massachusetts to Washington noticed, Coolidge intervened. The cumulative effect of removing the movie from local theaters gave an unmistakable rebuke to the Klan and those who had, up to then, failed to stand up to their intolerant agenda, including President Wilson himself. It would not be the only time Coolidge would, by simply doing the day’s work, upstage the sitting President. It was a resounding victory for those who regarded blacks not as second-class imports but as full citizens due the rights and privileges of citizenship under the Constitution and our laws.

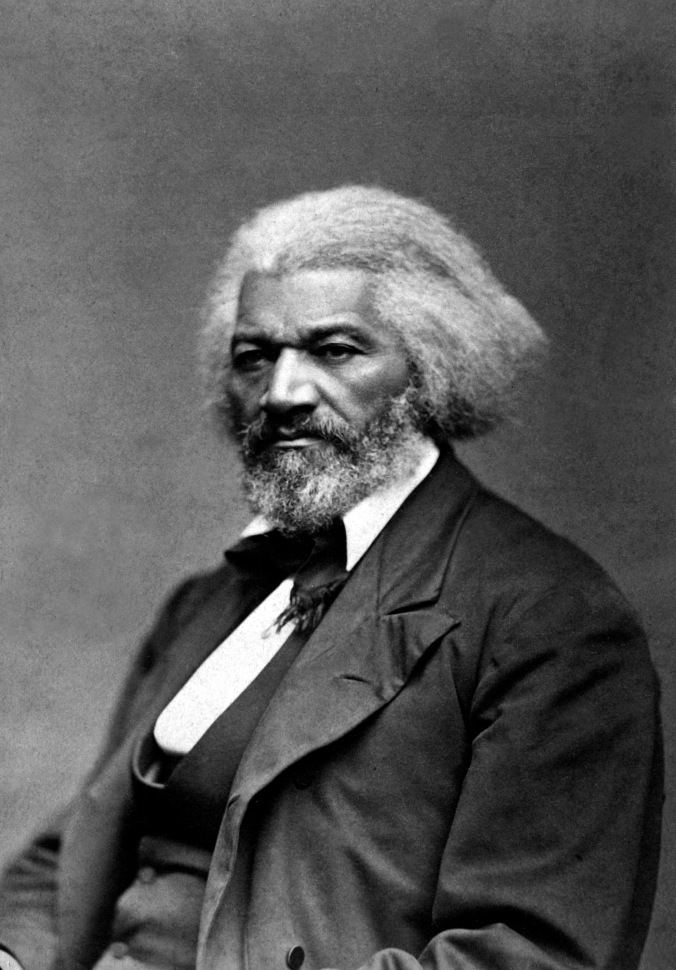

Frederick Douglass, 1879

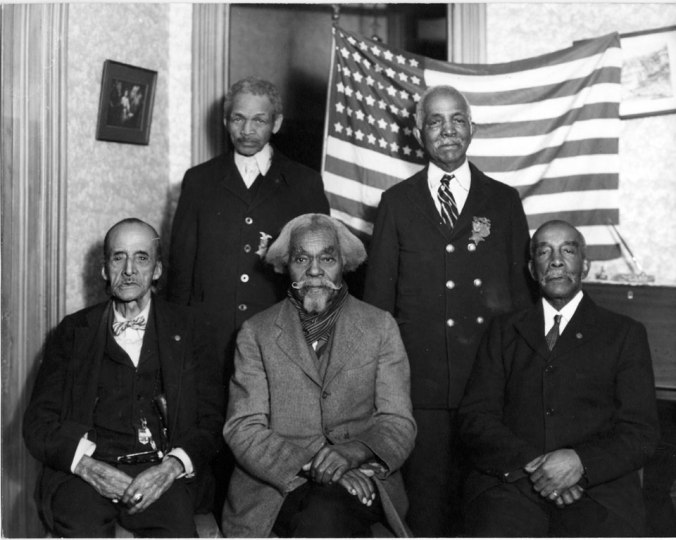

Hiram R. Revels, U.S. Senator, Mississippi (1870-1), c. 1870. Original photo by Matthew Brady.

Blanche Bruce, U. S. Senator, Mississippi (1875-1881)

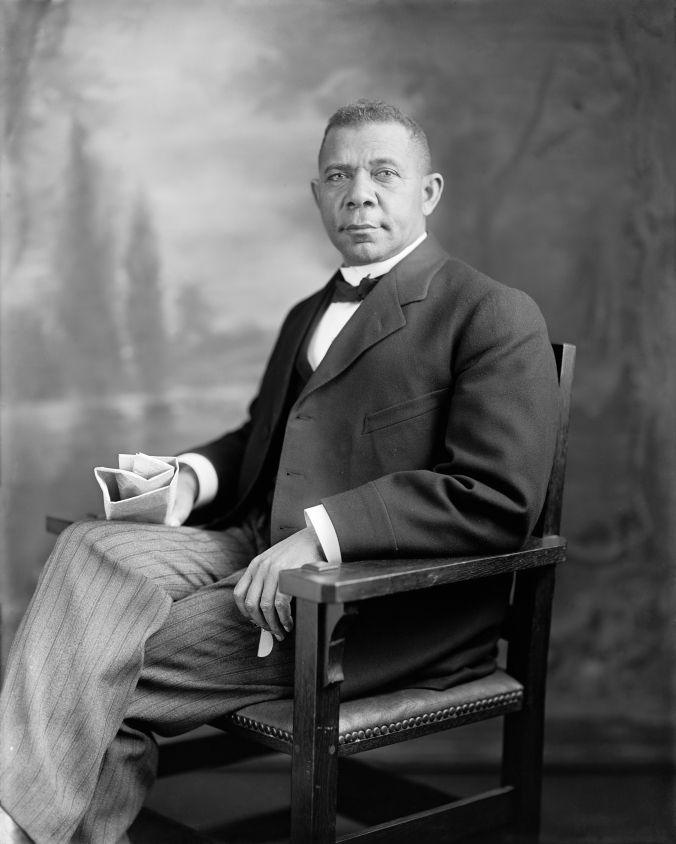

Booker T. Washington, founder of Tuskegee Institute

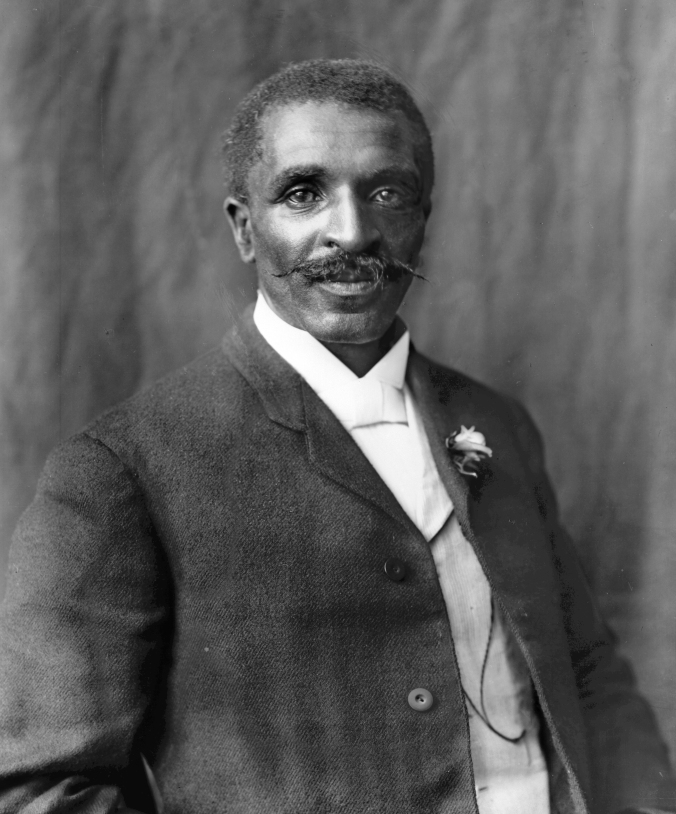

George Washington Carver, 1906. Photo by Frances Benjamin Johnston.

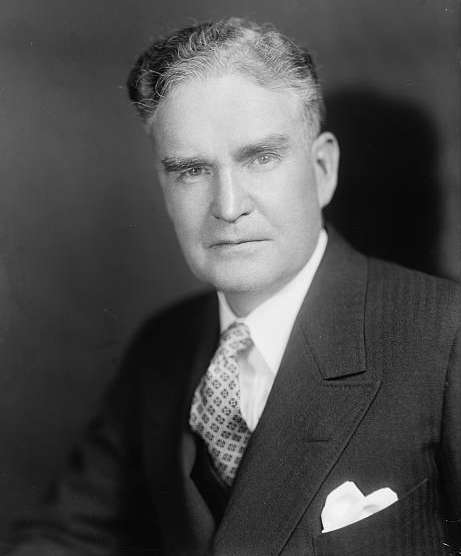

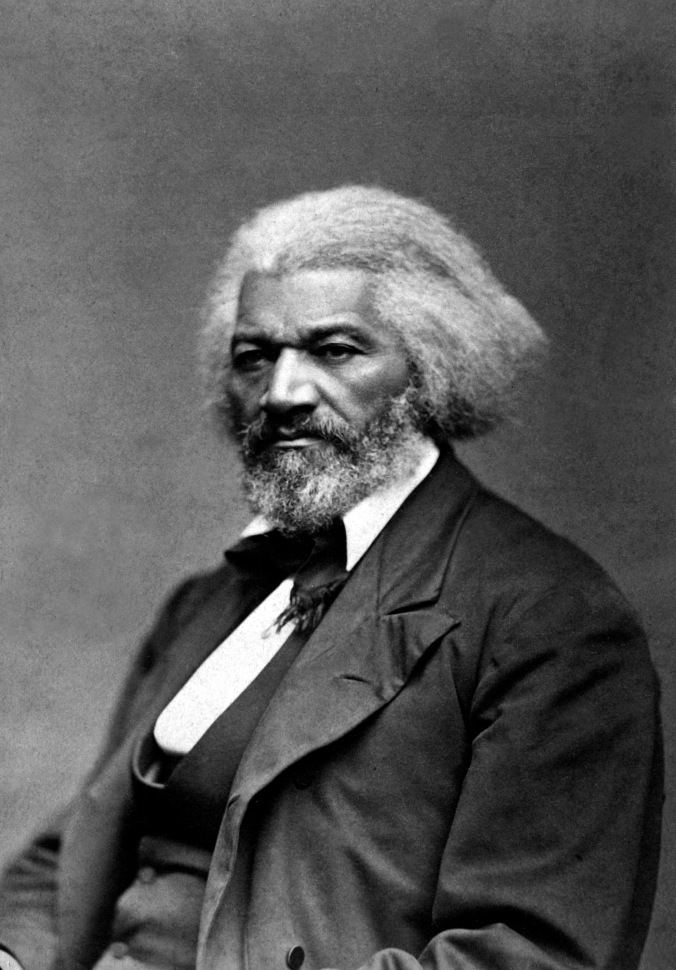

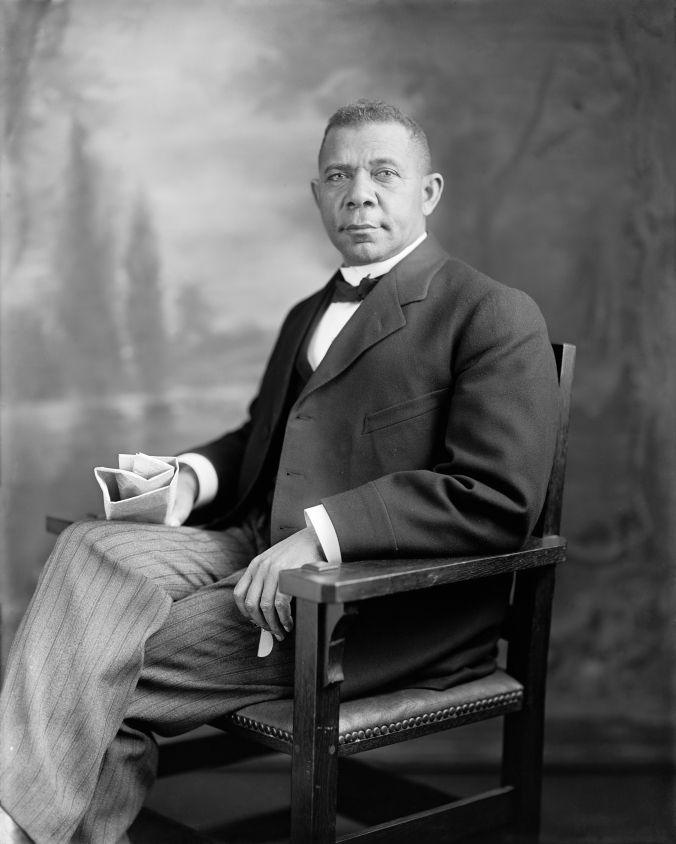

This insightful controversy, and especially Coolidge’s role in it, is little known and even less appreciated when it comes to the attitude of “Silent Cal” on race relations among “historians.” Both John L. Blair and Macco C. Dailey Jr., in writing on Coolidge and race, glaringly overlook this substantial event and simply accept, unquestioned, James W. Johnson’s impression of Coolidge written years after their White House meeting in February 1924. Furthermore, Dailey even claims there is no evidence that Coolidge had any exposure to black people or the issues concerning them until Mr. Johnson came to see him. For Blair, there is simply no room for interaction or mutual respect between blacks and a Republican Party so long classified as “white, Anglo-Saxon, Protestant.” Blair, writing of the electoral shift in party politics that moved blacks from Republican to Democrat support, discounts the first seventy years of GOP history. The Democrat claim of a “whites-only” Republican Party has to appropriate not only the end of slavery (a Republican achievement), the national influence of Republicans like Frederick Douglass, Hiram R. Revels, Blanche Bruce, Booker T. Washington, George W. Carver, among others, and an enlightened cultural tolerance in place today thanks to Democrat effort. In truth, history shows that Democrats have repeatedly and consistently obstructed the equality of blacks under the law, be it the filibuster of anti-lynching legislation in Coolidge’s day, blocking the famous Civil Rights Act of 1964 or exploiting racial discord for political advantage like those peddling permanent victimhood such as Jesse Jackson and Al Sharpton.

Since there is little institutional support for correcting the record, it is understandable why Blair and Dailey join the echo chamber of “scholars,” rather than question false premises. Still, it is a sad state of affairs when the minds most closed to know the truth are found in modern education. Having been weaned on a sour impression of Coolidge and his actions, or inaction (as they confidently maintain), nothing can exist to challenge that final and unequivocal conclusion, especially not the facts.

Had that one incident in 1915 been Coolidge’s only interaction with racial issues, the assertion might hold that he “did nothing,” timidly kept “silent” and left the problem for future leaders to finally “fix” injustice. In reality, Coolidge met the problem time and again throughout his five and a half years as President. Yet, like Coolidge understood (perhaps better than we today do), greater government activity does not translate into greater social equality. Has the mountain of legislation and executive activity over the last fifty years “fixed” racial inequality? Intolerance, bigotry and hatred reside in the hearts of people everywhere. Coolidge knew that government action had inescapable limits. Even the best laws and administrations are subject to it. As he once said, “Real reform does not begin with a law, it ends with a law. The attempt to dragoon the body when the need is to convince the soul will end only in revolt.” Such is the eternal nature of us humans. Americans are no more susceptible than anyone else. We were founded on the ideals of Christian forbearance, the Golden Rule and mutual respect but we, like the rest of the world, tend to reject those ennobling, exceptional standards for a base and mean norm, looking to public authorities to compensate for our personal deficiencies at self-government and self-control. There remains a reason why (particularly in our federalist system) law, and the government which enacts it, possesses these inherent limits. Coolidge, applying the principle consistently, saw what happened when individuals and local governments failed to meet their obligations; a higher authority would have to step into the vacuum. This held true whether the issue was flood control in 1927, agriculture in 1928, or enforcement against lynching in 1923. Coolidge, as usual, explains it best in an address at the College of William and Mary in 1926,

“It does not follow that because something ought to be done the National Government ought to do it. But, on the other hand, when the great body of public opinion of the Nation requires action the States ought to understand that unless they are responsive to such sentiment the national authority will be compelled to intervene. The doctrine of State rights is not a privilege to continue in wrong-doing but a privilege to be free from interference in well-doing. This Nation is bent on progress. It has determined on the policy of meting out justice between man and man. It has decided to extend the blessing of an enlightened humanity. Unless the States meet these requirements, the National Government reluctantly will be crowded into the position of enlarging its own authority at their expense. I want to see the policy adopted by the States of discharging their public functions so faithfully that instead of an extension on the part of the Federal Government there can be a contraction.”

That contraction, Coolidge would go on to say, places the burden of citizenship, maintaining the independence of action on local self-government. The better we govern ourselves, the less need there is for greater external authority, be it the State or the Federal Government. The contraction, as Coolidge termed it, of Washington’s involvement in American life was not something dreadful to be held with trepidation as a reversal of progress, it was progress toward our founding ideals. When Coolidge is criticized for not doing enough on race relations, or anything else, what the critic actually dislikes is Cal’s respect for America’s constitutional constraint of power and empowerment of local self-government.

Republican Leonidas C. Dyer, represented Missouri’s 12th Congressional District, 1911-1933

Powerful Senator William E. Borah, the “Lion of Idaho,” held office from 1907-1940

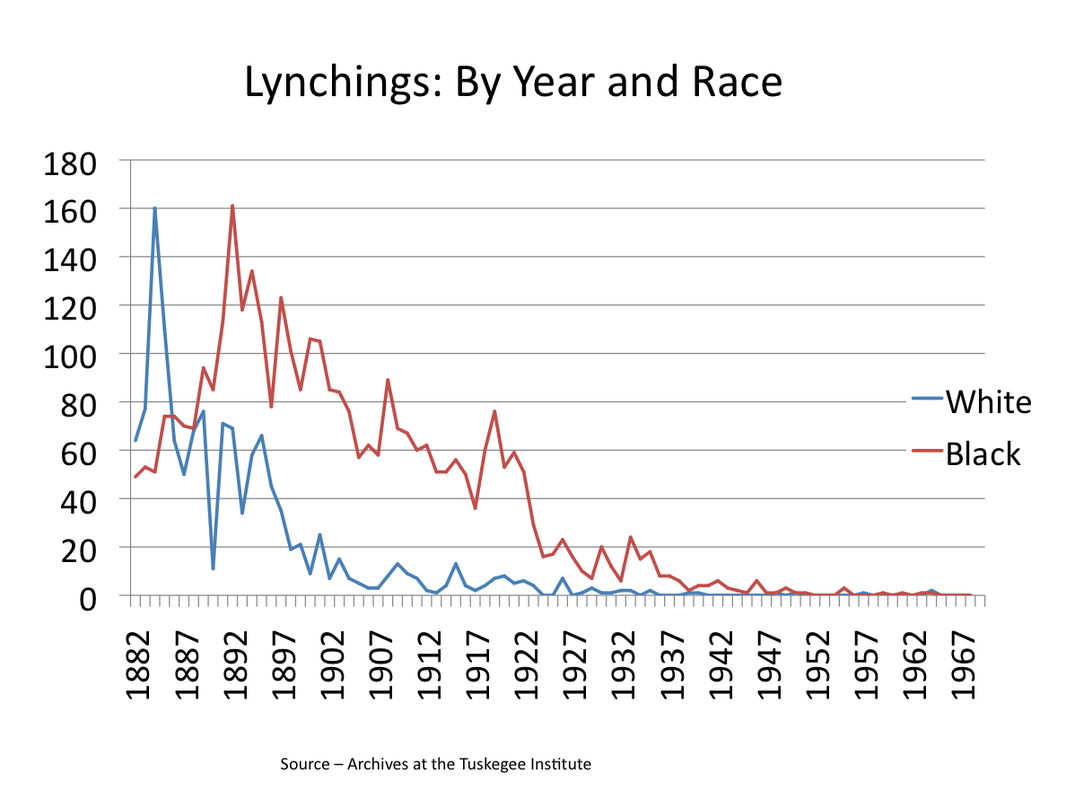

This is powerfully illustrated in the battle over the Dyer bill to make lynching, already a state offense in many localities, also a Federal crime subject to 5 years in prison, a $5,000 fine, or both, to an official who failed to act in his or her jurisdiction. Counties as well as individuals were subject to even harsher penalties if the law was not enforced against lynchers. Congressman Leonidas Dyer had seen the violence in his district of St. Louis back in 1917, the same year several race riots erupted, including one in Houston we will discuss momentarily. When the Tuskegee Institute began collecting a careful record of lynching numbers nationwide in 1882, the decade averaged 150 people, both white and black, annually. The number began coming down slowly in the years that followed but rose again during the Wilson years, peaking in 1915 (69 people) and even higher in 1919 (83 people). Still averaging sixty a year under Harding, the debate over Dyer’s bill reached its zenith in 1922. Introduced in 1918, Dyer had had an uphill fight from the beginning yet the House overwhelming passed the legislation in 1922 with the vote 231-119. Now pending before the Senate, it had to survive the Judiciary Committee and finally the full chamber. First, Senator Borah of Idaho, dependably contrary whatever the issue, gradually came to oppose the bill. Passing despite his resistance, it seemed that the bill would finally reach the President’s desk and become law. It never happened. The Democrats in the Senate commenced a filibuster and threatened to halt every other item of business until Republicans dropped Dyer’s legislation. Senate Republicans did soon thereafter. Not even President Harding, despite his Secretary’s promise to the contrary, would mention the campaign against lynching in his Annual Message that December. Perhaps it would just go away quietly?

Harding died the following August and it remained to be seen what position his successor would take until the first of his six annual messages to Congress, beginning on December 6, 1923, in which he declared,

“Numbered among our population are some 12,000,000 colored people. Under our Constitution their rights are just as sacred as those of any other citizen. It is both a public and private duty to protect those rights. The Congress ought to exercise all its powers of prevention and punishment against the hideous crime of lynching, of which the negroes are by no means the sole sufferers, but for which they furnish a majority of the victims.”

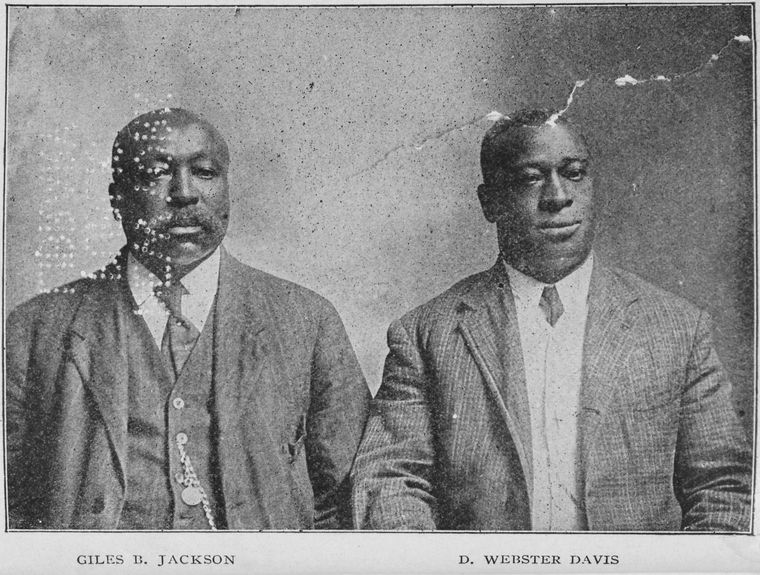

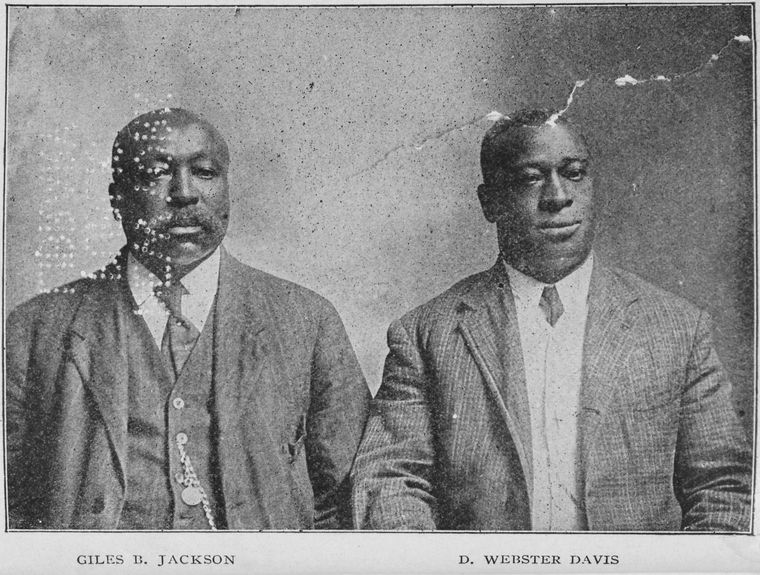

Lawyer Giles B. Jackson and Educator-Author D. Webster Davis photographed together in 1911, both rose from slavery to successful lives of public service

President Coolidge did not stop there, he went on to express his support for other efforts underway, including, of all things, an appropriation for vocational training, another half million for Howard University’s medical program to expand the already successful work of training doctors, and endorsing Giles B. Jackson’s effort to get Congress to create a commission of “mutual understanding” that would work together in the growth and development of economic opportunity between the races. Coolidge would not let it alone either. On December 3, 1924, Coolidge said,

“I firmly believe that it is better for all concerned that they [“colored” people] should be cheerfully accorded their full constitutional rights, that they should be protected from all of those impositions to which, from their position, they naturally fall a prey, especially from the crime of lynching and that they should receive every encouragement to become full partakers in all the blessings of our common American citizenship.”

The country knew he was not only addressing the Dyer bill but also disenfranchisement and segregation. In October of the following year, he would bravely head to Omaha, where the Klan had done their best to stir up prejudice and resentment with their cloaked motto, “America First.” To the cheers of black Americans around the country, President Coolidge before the American Legion convened there, underscored the common heritage all those holding the name “American” rightly possesses. Americans of all backgrounds had served in the recent World War, fighting for the same cause, united toward the same goals and purpose. Now that war was passed, it was no different for everyone to live at peace with his neighbor. The ideal of “America first,” he said, was not inherently wrong, it was how such an aim was being carried out.

Walter Francis White, secretary of the NAACP, was an early correspondent with the Coolidge White House. Americans, white and black, were not looking for a complete overhaul of society by civil rights legislation in the 1920s. White’s requests were much simpler and far more practical: (1) Turn the Veterans Hospital at Tuskegee entirely over to “colored” administrators; and (2) Support the Dyer bill against lynching. Coolidge fulfilled both requests and more.

“It can not be done,” Coolidge proclaimed, “by the cultivation of national bigotry, arrogance, or selfishness. Hatreds, jealousies, and suspicions will not be productive of any benefits in this direction. Here again we must apply the rule of toleration. Because there are other peoples whose ways are not our ways, and whose thoughts are not our thoughts, we are not warranted in drawing a conclusion that they are adding nothing to the sum of civilization. We can make little contribution to the welfare of humanity on the theory that we are a superior people and all others are an inferior people. We do not need to be too loud in the assertion of our own righteousness. It is true that we live under most favorable circumstances. But before we come to the final and irrevocable decision that we are better than everybody else we need to consider what we might do if we had their provocations and their difficulties…

“We can only make America first in the true sense which that means by cultivating a spirit of friendship and good will, by the exercise of the virtues of patience and forbearance, by being ‘plenteous in mercy,’ and through progress at home and helpfulness abroad standing as an example of real service to humanity…

“If our country is to have any position of leadership, I trust it may be in that direction, and I believe that the place where it should begin is at home. Let us cast off our hatreds…

“If we are to maintain and perfect our own civilization, if we are to be of any benefit to the rest of mankind, we must turn aside from the thoughts of destruction and cultivate the thoughts of construction. We can not place our main reliance upon material forces. We must reaffirm and reinforce our ancient faith in truth and justice, in charitableness and tolerance. We must make our supreme commitment to the everlasting spiritual forces of life. We must mobilize the conscience of mankind.”

Troops of the 24th Infantry, in a photo taken at Yosemite National Park sometime in the early years of the twentieth century. The 24th Infantry was deployed to resolve more civil conflicts than any other unit. Coolidge authorized the early release of 20 black soldiers originally under sentence of death or life imprisonment for taking part in the race riots in Houston, August 1917.

Coolidge continued to bring pressure to bear for that mobilization of conscience. In December of that same year, 1925, Coolidge brought the issue before Congress again, reminding them of their unfinished business, the Negro race needed “reassurance that the requirements of the Government and society to deal out to them even-handed justice will be met. They should be protected from all violence and supported in the peaceable enjoyment of the fruits of their labor.” Then Coolidge came to the point, “Those who do violence to them should be punished for their crimes. No other course of action is worthy of the American people…It is fundamental of our institutions that they seek to guarantee to all our inhabitants the right to live their own lives under the protection of the public law. This does not include any license to injure others…But it does mean the full right to liberty and equality before the law without distinction of race or creed.” He would not, however, exceed his duty by using coercion, taking reprisals if certain Senators or Representatives failed to do their job (The Autobiography p.232). They are not his representatives, the people are to hold them accountable as their delegated representation. As Dyer would reintroduce the legislation for the last time in 1926, Coolidge did not consider the matter dead. “The social well-being of our country requires our constant effort for the amelioration of race prejudice and the extension to all elements of equal opportunity and equal protection under the laws which are guaranteed by the Constitution…our duty…requires us to use all our power to protect them from the crime of lynching. Although violence of this kind has very much decreased, while any of it remains we can not justify neglecting to make every effort to eradicate it by law.”

In December 1927, Coolidge continued his annual report to Congress, black Americans “have been the recipients of presidential appointments and their professional ability has arisen to a sufficiently high plane so that they have been intrusted with the entire management and control of the great veterans hospital at Tuskegee, where their conduct has taken high rank. They have shown that they have been worthy of all the encouragement which they have received. Nevertheless, they are too often subjected to thoughtless and inconsiderate treatment, unworthy alike of the white or colored races. They have especially been made the target of the foul crime of lynching. For several years these acts of unlawful violence had been diminishing. In the last year they have shown an increase. Every principle of order and law and liberty is opposed to this crime. The Congress should enact any legislation it can under the Constitution to provide for its elimination.”

Finally, when nearly everyone had given up on Congress doing anything, Coolidge took his incessant thrust at Congress in his final message (contrary to Blair’s claim he abandoned the cause by this time), “For 65 years now our negro population has been under the peculiar care and solicitude of the National Government. The progress which they have made in education and the professions, in wealth and in the arts of civilization, affords one of the most remarkable incidents in this period of world history…Whatever doubt there may have been of their capacity to assume the status granted to them by the Constitution of this Union is being rapidly dissipated. Their cooperation in the life of the Nation is constantly enlarging. Exploiting the Negro problem for political ends is being abandoned and their protection is being increased by those States in which their percentage of population is largest. Every encouragement should be extended for the development of the race” in the just application of State laws against the “crime of lynching” reinforced by “such immediate remedial legislation as the Federal Government can extend under the Constitution.”

Without a single law yet passed, the number had plummeted to 17 that year, from what had for so many years been over a hundred people lynched annually. By 1929 the total for the entire year had fallen to 10 people. How was this possible? Some, like James W. Johnson and Leonidas Dyer, attribute it to the impact of their lynching bill on existing local enforcement. It was federalism functioning as intended. While improved enforcement certainly had an impact, so did Coolidge for keeping the heat on Congress. This was not the only reason, however, when considered beside the reduction of income taxes spearheaded by Coolidge and Mellon in chopping rates down to 25 per cent by 1928, exempting most Americans from having to pay. Combined with the constructive economy initiative pushed by Coolidge and his Budget Bureau Director, Herbert Lord, all Americans were able to keep more of what they earned for themselves, rather than Washington. Of course, as experience revealed, the States commenced heavy spending practices that placed the Federal Government in the remarkable position of being better placed fiscally than several of the State governments when Coolidge left office.

Cartoon by Charles Berryman, February 12, 1924

Words are great, very potent instruments for fostering historic advancement but Coolidge did not stop there. He acted. His actions were not always comprehended at the time, whether it was appointing C. Bascom Slemp to serve as Secretary to the President or reappointing Colonel C. O. Sherill over Public Buildings, Grounds and Parks. In time, his selection of Slemp would be hailed as one of many saavy choices to advance the welfare of everyone, not merely one segment of the country. Even his choice to succeed Harlan Stone at the Justice Department, Charles B. Warren, was lauded by blacks for his strong support of equal and impartial application of the law. He would replace Colonel Sherrill with Lieutenant Colonel Grant, who would abruptly end segregation in his bureau and tear down the “white pool” constructed during the Wilson years without simultaneously providing a beach area for blacks. His appointment of first Harlan F. Stone and then John G. Sargent would shut down the institutional prejudice of previous departments. As each year’s departmental reports showed, discrimination was declining, wages of $53 million were increasing, employment practices were returned to a meritorious basis (growing personnel to an historic 51,800 in Federal service), while black Americans were experiencing the blessings of home ownership, self-employment and increased capital, reaching into every field from medicine and law to industry and agriculture (Blair, “A Time for Parting: the Negro during the Coolidge Years,” Journal of American Studies 3.2 [December 1969]: 183; “African Americans and the Consumer Economy,” http://lcweb2.loc.gov:8081/ammem/amrlhtml/inafamer.html). Coolidge would approve the first all-Negro commission dispatched diplomatically to the Virgin Islands in 1924 to investigate the social and commercial conditions of the protected islands and make recommends for future policy. Among the commission’s nine recommendations were: (1) strengthening traditional marriage and the home; (2) building up the ties in educational institutions in America and the Islands; and (3) Upholding clear standards for immigration and citizenship on the Islands.

Colonel Ulysses S. Grant III

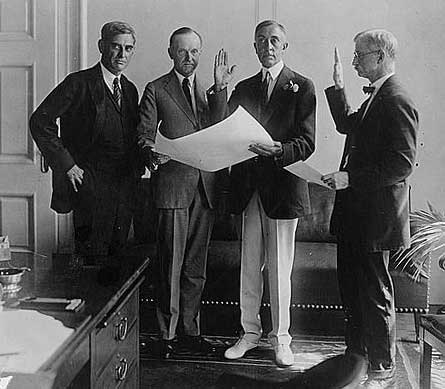

C. Bascom Slemp, in white trousers, being sworn in as Secretary to the President, September 4, 1923

A letter dated September 3, 1924 from C. Bascom Slemp to W. D. Johnson of New York, concerning fears about his as well as Coolidge’s resolve when it comes to racial conflict. Slemp, loyal to his chief despite having voted against the Dyer bill back in 1922 as a Congressman writes of Coolidge, “he has in one of his messages to Congress referred most sympathetically to this measure, and I have every reason to believe that his attitude will continue friendly and helpful toward it.” Indeed, his attitude did. A fascinating chain of correspondence (including this document) can be found at http://lcweb2.loc.gov/cgi-bin/ampage. “Prosperity and Thrift: The Coolidge Era and the Consumer Economy, 1921-1929”

Coolidge stood by those chosen for official responsibility, an impressive list of qualified men and women in an era and by a man who supposedly accomplished nothing for civil rights: renewing the appointments of Charles Anderson as Collector of Internal Revenue and Walter L. Cohen as Louisiana’s Controller of Customs (keeping him as a recess appointment over Senate rejection); selecting Arthur Froe as Recorder of Deeds for the illustrious District of Columbia; giving full control of the Veterans Hospital at Tuskegee to “colored” directors, doctors and support staff; appointing James A. Cobb as a judge of the D.C. Municipal Court; William F. Francis as U.S. Minister to Liberia; and George H. Woodson, Cornelius R. Richardson, Charles E. Mitchell, W. H. C. Brown, and Jefferson S. Coage as the Commission to the Virgin Islands. Among his political team, he collaborated with the talented Emmet Jay Scott, William Matthews and Hallie Q. Brown to promote a campaign that Scott called “constructionalism,” appealing not to black victimhood or affirmative action but initiative, self-reliance and economic opportunity rather than legislative lobbyism.

Charles W. Anderson, reappointed by Coolidge as Collector of Internal Revenue for New York’s second district. It was a district that included Wall Street.

James A. Cobb was appointed by Coolidge in 1925 as a federal judge of the D.C. Municipal Court to succeed the first black man so honored, Robert H. Terrell, nominated by President Taft in 1910. Coolidge sought the most qualified men, finding the notion of special seats for race or religion to be abhorrent and insulting.

William T. Francis, appointed by Coolidge to serve as Minister Resident and Consul General to Liberia, July 12, 1927. He was an imminently qualified lawyer, a graduate of St. Paul’s William Mitchell College of Law.

Charles E. Mitchell of West Virginia, one of five to serve on the Commission approved by President Coolidge whom he tasked with setting policy on the Virgin Islands. This was the first time in American history a delegation, completely comprised of blacks, was dispatched in an official capacity by any President. The other four commissioners were well-known and respected leaders in their states: George Henry Woodson of Iowa, Cornelius R. Richardson of Indiana, W. H. C. Brown of Virginia, and Jefferson S. Coage of Delaware. Photo from The New York Age, November 8, 1924.

Emmett Jay Scott of Texas, had served as Dr. Washington’s right-hand man at Tuskegee. He documented and published a work on black Americans who served in World War I, had already worked in the War Department during that conflict and while Secretary-Treasurer of Howard University also led the advance of “constructionalism” among black Americans during the 1924 campaign to “Keep Coolidge.” 1,308,000 blacks voted to keep Cal that year.

Hallie Quinn Brown of Pennsylvania was a tireless Republican grassroots activist. She helped establish women’s clubs in Ohio and directed the effort across the country through the National Association of Colored Women from 1920-1924. She spoke at the 1924 convention and helped to ensure Coolidge won that November. This is a picture from a book she published in 1926.

Coolidge did more, he cut a year and a half from the sentences of members of the 24th Infantry imprisoned for their part in the Houston riots of 1917, he commuted the sentence of Jamaican national, Marcus Garvey, offered the post to W. E. B. DuBois representing America at the inauguration of Liberia’s President, Charles B. D. King and by working closely with Robert Moton of Tuskegee Institute along with Emmett Scott of Howard University, secured annual appropriations for improving academic programs. Furthermore, through his support of Howard University, the first permanent black president, Mordecai Johnson, was inaugurated in 1927. In each instance, when petitioned, he responded honestly and in typical Coolidge fashion, conscientiously following up behind the scenes even when it took years to obtain resolution. When word reached Coolidge that the Commissioner of Pensions had segregated four black Examiners in his bureau, he issued clear orders: “the President directs you to revoke such segregation at once.” Coolidge would not issue blanket commands, however, unrelated to specific violations, insensitive to the host of unintended consequences such a blind exercise of authority would unleash, potentially harming the people he meant to help. He believed in the power of the morally right to ultimately prevail, a power no Congress or President can invent or otherwise administer through legislation or executive order without the individual’s will to choose tolerance over prejudice and service over hatred. As Coolidge potently affirms, “Bigotry is only another name for slavery. It reduces to serfdom not only those against whom it is directed, but also those who seek to apply it. An enlarged freedom can only be secured by the application of the golden rule. No other utterance ever presented such a practical rule of life.” Quite a record for someone dismissed as a “silent, do nothing” President, don’t you agree?

For further reading:

Hasian Jr., Marouf. “Calvin Coolidge and the Rhetoric of ‘Race’ in the 1920s,” chapter 2 of Civil Rights Rhetoric and the American Presidency. Eds. James Arnt Aune and Enrique D. Rigsby. College Station: Texas A & M University Press, 2005. Hasian does a fair job dispelling the notion that Coolidge was “silent” on the issues of race relations and they even understand the opposition the thirtieth president had and certainly would continue to have for government’s array of social engineering experiments. An interesting walk through Coolidge’s era alongside eugenics, segregation, the Klan and the rest of the “race problem.”

Johnson, Charles C. Why Coolidge Matters: Leadership Lessons from America’s Most Underrated President. New York: Encounter Books, 2013. It is primarily in chapter six, “The Possibilities of the Soul” (pages 164-186), that you will find an excellent exposition of Coolidge’s thoughts on race.

O’Reilly, Kenneth. Nixon’s Piano: Presidents and Racial Politics from Washington to Clinton. New York: Free Press, 1995. O’Reilly angrily asserts that the only two men to accomplish anything constructive for race relations were Abraham Lincoln and Lyndon Johnson. Mr. O’Reilly needs to get out more.

Sherman, Richard B. The Republican Party and Black America From McKinley to Hoover 1896-1933. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1973. Like the rest, Sherman parrots the same “Coolidge didn’t do enough” line but his explanation of the struggle to advance anti-lynching legislation (chapter 7) is both clear and informative.